What Joe Biden Can’t Bring Himself to Say

His verbal stumbles have voters worried about his mental fitness. Maybe they’d be more understanding if they knew he’s still fighting a stutter.

His eyes fall to the floor when I ask him to describe it. We’ve been tiptoeing toward it for 45 minutes, and so far, every time he seems close, he backs away, or leads us in a new direction. There are competing theories in the press, but Joe Biden has kept mum on the subject. I want to hear him explain it. I ask him to walk me through the night he appeared to lose control of his words onstage.

“I—um—I don’t remember,” Biden says. His voice has that familiar shake, the creak and the croak. “I’d have to see it. I-I-I don’t remember.”

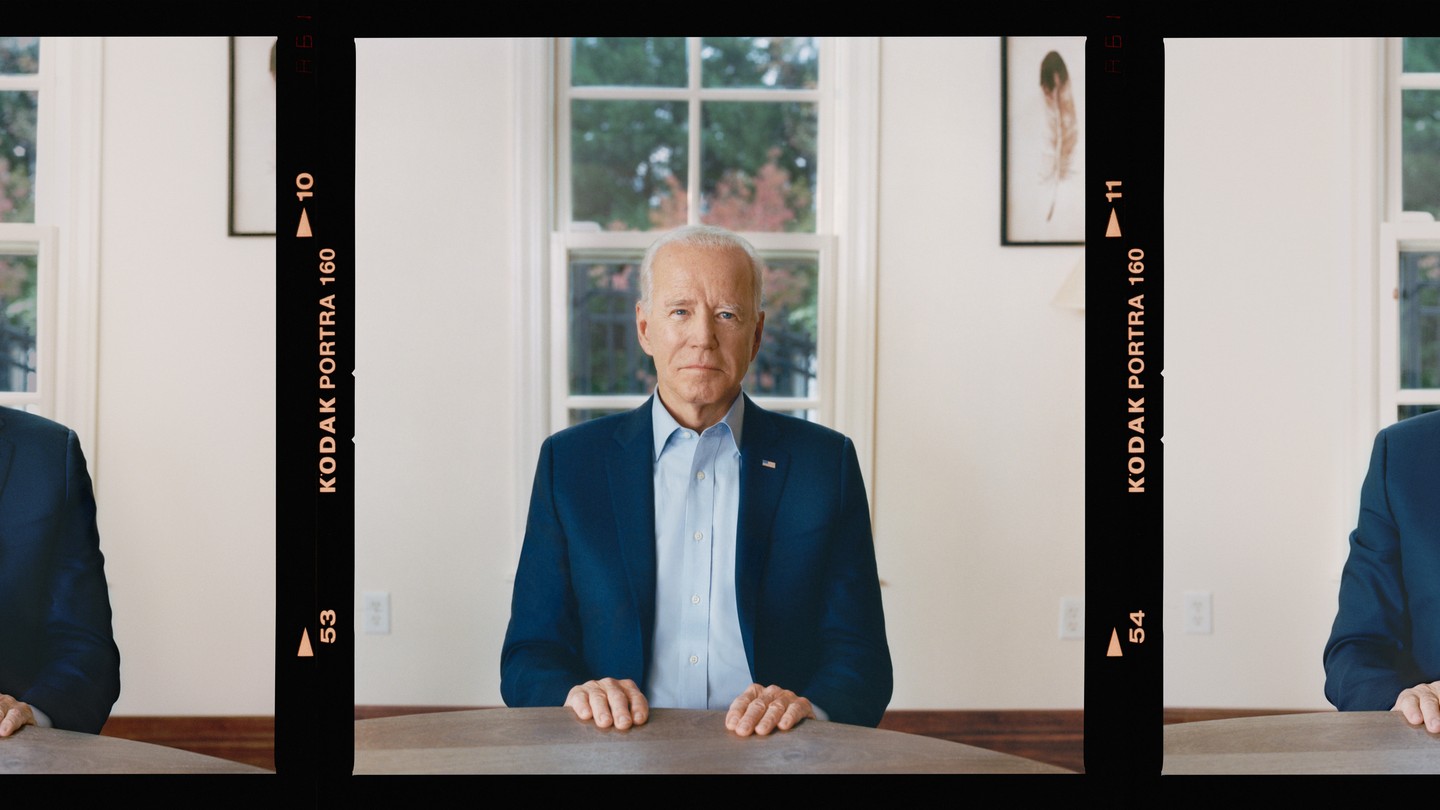

We’re in Biden’s mostly vacant Washington, D.C., campaign office on an overcast Tuesday at the end of the summer. Since entering the Democratic presidential-primary race in April, Biden has largely avoided in-depth interviews. When I first reached out, in late June, his press person was polite but noncommittal: Was an interview really necessary for the story?

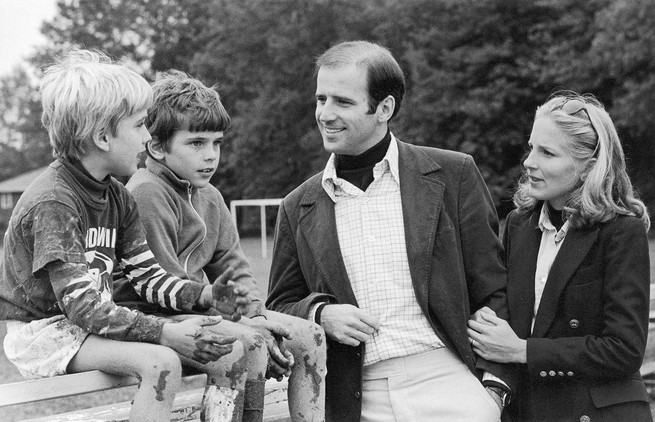

Then came the second debate, at the end of July, in Detroit. The first one, a month earlier, had been a disaster for Biden. He was unprepared when Senator Kamala Harris criticized both his past resistance to federally mandated busing and a recent speech in which he’d waxed fondly about collaborating with segregationist senators. Some of his answers that night had been meandering and difficult to parse, feeding into the narrative that he wasn’t just prone to verbal slipups—he’s called himself a “gaffe machine”—but that his age was a problem, that he was confused and out of touch.

Detroit was Biden’s chance to regain control of the narrative. And then something else happened. The candidates were talking about health care. At first, Biden sounded strong, confident, presidential: “My plan makes a limit of co-pay to be One. Thousand. Dollars. Because we—”

He stopped. He pinched his eyes closed. He lifted his hands and thrust them forward, as if trying to pull the missing sound from his mouth. “We f-f-f-f-further

support—” He opened his eyes. “The uh-uh-uh-uh—” His chin dipped toward his chest. “The-uh, the ability to buy into the Obamacare plan.” Biden also stumbled when trying to say immune system.

Fox News edited these moments into a mini montage. Stifling laughter, the host Steve Hilton narrated: “As the right words struggled to make that perilous journey from Joe Biden’s brain to Joe Biden’s mouth, half the time he just seemed to give up with this somewhat tragic and limp admission of defeat.”

Several days later, Biden’s team got back in touch with me. One of his aides gingerly asked whether I’d noticed the former vice president stutter during the debate. Of course I had—I stutter, far worse than Biden. The aide said he was ready to talk about it. In November, after Biden stumbled multiple times during a debate in Atlanta, the topic would become even more relevant.

“So how are you, man?”

Biden is in his usual white button-down and navy suit, a flag pin on the left lapel. Up close, he looks like he’s lost weight since leaving office in 2017. His height is commanding, but, as he approaches his 77th birthday, he doesn’t fill out his suit jacket like he used to.

I stutter as I begin to ask my first question. “I’ve only … told a few people I’m … d-doing this piece. Every time I … describe it, I get … caught on the w-word-uh stuh-tuh-tuh-tutter.”

“So did I,” Biden replies. “It doesn’t”—he interrupts himself—“can’t define who you are.”

Maybe you’ve heard Biden talk about his boyhood stutter. A non-stutterer might not notice when he appears to get caught on words as an adult, because he usually maneuvers out of those moments quickly and expertly. But on other occasions, like that night in Detroit, Biden’s lingering stutter is hard to miss. He stutters—if slightly—on several sounds as we sit across from each other in his office. Before addressing the debate specifically, I mention what I’ve just heard. “I want to ask you, as, you know, a … stutterer to, uh, to a … stutterer. When you were … talking a couple minutes ago, it, it seemed to … my ear, my eye … did you have … trouble on s? Or on … m?”

Biden looks down. He pivots to the distant past, telling me that the letter s was hard when he was a kid. “But, you know, I haven’t stuttered in so long that it’s

hhhhard for me to remember the specific—” He pauses. “What I do remember is the feeling.”

I started stuttering at age 4.

I still struggle to say my own name. When I called the gas company recently, the automated voice apologized for not being able to understand me. This happens a lot, so I try to say “representative,” but r’s are tough too. When I reach a human, I’m inevitably asked whether we have a poor connection. Busy bartenders will walk away and serve someone else when I take too long to say the name of a beer. Almost every deli guy chuckles as I fail to enunciate my order, despite the fact that I’ve cut it down to just six words: “Turkey club, white toast, easy mayo.” I used to just point at items on the menu.

My head will shake on a really bad stutter. People have casually asked whether I have Parkinson’s. I curl my toes inside my shoes or tap my foot as a distraction to help me get out of it, a behavior that I’ve repeated so often, it’s become a tic. Sometimes I shuffle a pen between my hands. When I was little, I used to press my palm against my forehead in an effort to force the missing word out of my brain. Back then, my older brother would imitate this motion and the accompanying sound, a dull whine—something between a cow and a sheep. A kid at baseball camp, Michael, referred to me as “Stutter Boy.” He’d snap his fingers and repeat it as if calling a dog. “Stutter Boy! Stutter Boy!” In college, I applied for a job at a coffee shop. I stuttered horribly through the interview, and the owner told me he couldn’t hire me, because he wanted his café to be “a place where customers feel comfortable.”

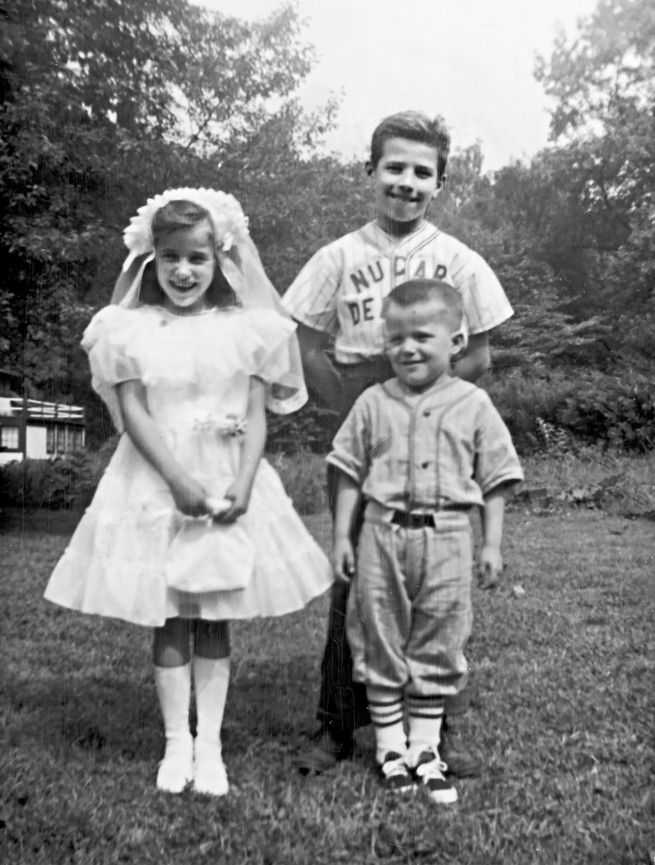

Stuttering is a neurological disorder that affects roughly 70 million people, about 3 million of whom live in the United States. It has a strong genetic component: Two-thirds of stutterers have a family member who actively stutters or used to. Biden’s uncle on his mother’s side—“Uncle Boo-Boo,” as he was called—stuttered his whole life.

In the most basic sense, a stutter is a repetition, prolongation, or block in producing a sound. It typically presents between the ages of 2 and 4, in up to twice as many boys as girls, who also have a higher recovery rate. During the developmental years, some children’s stutter will disappear completely without intervention or with speech therapy. The longer someone stutters, however, the lower the chances of a full recovery—perhaps due to the decreasing plasticity of the brain. Research suggests that no more than a quarter of people who still stutter at 10 will completely rid themselves of the affliction as adults.

The cultural perception of stutterers is that they’re fearful, anxious people, or simply dumb, and that stuttering is the result. But it doesn’t work like that. Let’s say you’re in fourth grade and you have to stand up and recite state capitals. You know that Juneau is the capital of Alaska, but you also know that you almost always block on the j sound. You become intensely anxious not because you don’t know the answer, but because you do know the answer, and you know you’re going to stutter on it.

Stuttering can feel like a series of betrayals. Your body betrays you when it refuses to work in concert with your brain to produce smooth speech. Your brain betrays you when it fails to recall the solutions you practiced after school with a speech therapist, allegedly in private, later learning that your mom was on the other side of a mirror, watching in the dark like a detective. If you’re a lucky stutterer, you have friends and family who build you back up, but sometimes your protectors betray you too.

A Catholic nun betrayed Biden when he was in seventh grade. “I think I was No. 5 in alphabetical order,” Biden says. He points over my right shoulder and stares into the middle distance as the movie rolls in his mind. “We’d sit along the radiators by the window.”

The office we’re in is awash in framed memories: Biden and his family, Biden and Barack Obama, Biden in a denim shirt posing for InStyle. The shelf behind the desk features, among other books, Jon Meacham’s The Soul of America. It’s a phrase Biden has adopted for his campaign this time around, his third attempt at the presidency. In almost every speech, Biden warns potential voters that 2020 is not merely an election, but a battle “for the soul of America.” Sometimes he swaps in nation.

But now we’re back in middle school. The students are taking turns reading a book, one by one, up and down the rows. “I could count down how many paragraphs, and I’d memorize it, because I found it easier to memorize than look at the page and read the word. I’d pretend to be reading,” Biden says. “You learned early on who the hell the bullies were,” he tells me later. “You could tell by the look, couldn’t you?”

For most stutterers, reading out loud summons peak dread. A chunk of text that may take a fluent person roughly a minute to read could take a stutterer five or 10 times as long. Four kids away, three kids away. Your shoulders tighten. Two away. The back of your neck catches fire. One away. Then it happens, and the room fills with secondhand embarrassment. Someone breathes a heavy sigh. Someone else laughs. At least one kid mimics your stutter while you’re actively stuttering. You never talk about it. At night, you stare at the ceiling above your bed, reliving it.

“The paragraph I had to read was: ‘Sir Walter Raleigh was a gentleman. He laid his cloak upon the muddy road suh-suh-so the lady wouldn’t soil her shoes when she entered the carriage,’ ” Biden tells me, slightly and unintentionally tripping up on the word so. “And I said, ‘Sir Walter Raleigh was a gentle man who—’ and then the nun said, ‘Mr. Biden, what is that word?’ And it was gentleman that she wanted me to say, not gentle man. And she said, ‘Mr. Buh-Buh-Buh-Biden, what’s that word?’ ”

Biden says he rose from his desk and left the classroom in protest, then walked home. The family story is that his mother, Jean, drove him back to school and confronted the nun with the made-for-TV phrase “You do that again, I’ll knock your bonnet off your head!” I ask Biden what went through his mind as the nun mocked him.

“Anger, rage, humiliation,” he says. His speech becomes staccato. “A feeling of, uh—like I’m sure you’ve experienced—it just drops out of your chest, just, like, you feel … a void.” He lifts his hands up to his face like he did on the debate stage in July, to guide the v sound out of his mouth: void.

By all accounts, Biden was both popular and a strong athlete in high school. He was class president at Archmere Academy, in Claymont, Delaware. His nickname was “Dash”—not a reference to his speed on the football field, but rather another way to mock his stutter. “It was like Morse code—dot dot dot, dash dash dash dash,” Biden says. “Even though by that time I started to overcome it.”

I ask him to expand on the relationship between anger and humiliation, or shame.

“Shame is a big piece of it,” he says, then segues into a story about meeting a stutterer while campaigning.

I bring it back up a little later, this time more directly: “When have you felt shame?”

“Not for a long, long, long time. But especially when I was in grade school and high school. Because that’s the time when everything is, you know, it’s rough. They talk about ‘mean girls’? There’s mean boys, too.”

Bill Bowden had the locker next to Biden’s at Archmere. I called Bowden recently. “It was just kind of a funny thing, you know?” he told me. “Hopefully he wasn’t hurt by it.” Bob Markel, another high-school buddy of Biden’s, went a little further when we spoke: “ ‘H-H-H-H-Hey, J-J-J-J-J-Joe B-B-B-B-Biden’—that’s how he’d be addressed.” Markel said the Archmere guys called him “Stutterhead,” or “Hey, Stut !” for short. He fears that he himself may have made fun of Biden once or twice. “I never remember him being offended. He probably was,” Markel said. “I think one of his coping mechanisms was to not show it.” Bowden and Markel have remained friends with Biden to this day.

Before collecting from customers on his paper route, Biden would preplay conversations in his mind, banking lines—a tactic he still sometimes uses on the campaign trail, he says. “I knew the one guy loved the Phillies. And he’d asked me about them all the time. And I knew another person would ask me about my sister, so I would practice an answer.”

After trying and failing at speech therapy in kindergarten, Biden waged a personal war on his stutter in his bedroom as a young teen. He’d hold a flashlight to his face in front of his bedroom mirror and recite Yeats and Emerson with attention to rhythm, searching for that elusive control. He still knows the lines by heart: “Meek young men grow up in libraries, believing it their duty to accept the views, which Cicero, which Locke, which Bacon, have given, forgetful that Cicero, Locke, and Bacon were only young men in libraries, when they wrote these books.”

Biden performs the passage for me with total fluency, knowing where and when to pause, knowing how many words he can say before needing a breath. This is what stutterers learn to do: reclaim control of their airflow; think in full phrases, not individual words. I ask Biden what his moment of dread used to be in that essay.

“Well, looking back on it, ‘Meek young men grow up in li-li-libraries,’ ” he begins again. “ ‘Li’—the l.”

“That kind of sound, the l sound, is like the … r sound,” I say.

“Yes.”

“Sometimes I’ve noticed, watching old clips, it looks like you do have a little trouble on the r. It’s your middle initial.”

“Yeah.”

“Like ‘ruh-ruh-ruh-remember,’ ” I say, intentionally stuttering on the r.

“Well, I may. I-I-I-I-I haven’t thought I have. But I-I-I-I don’t doubt there’s probably ways people could pick up that there’s something. But I don’t consciously think of it anymore.”

Biden says he hasn’t felt himself caught in a traditional stutter in several decades. “I mean, I can’t remember a time where I’ve ever worried before a crowd of 80,000 people or 800 people or 80 people—I haven’t had that feeling of dread since, I guess, speech class in college,” he says, referring to an undergraduate public-speaking course at the University of Delaware.

This is when I ask him what happened that night in Detroit.

After saying he doesn’t remember, Biden opines: “I’m everybody’s target; they have to take me down. And so, what I found is—not anymore—I’ve found that it’s difficult to deal with some of the criticism, based on the nature of the person directing the criticism. It’s awful hard to be, to respond the same way in a national debate—especially when you’re, you know, the guy who is characterized as the white-guy-of-privilege kind of thing—to turn and say to someone who says, ‘I’m not saying you’re a racist, but …’ and know you’re being set up. So I have to admit to you, I found my mind going, What the hell? How do I respond to that? Because I know she’s being completely unfair.”

I eventually realize that he’s describing the moment from the first debate, when Harris criticized his record on race.

“These aren’t debates,” he continues. “These are one-minute assertions. And I don’t think there’s anybody who hasn’t been taking shots at me, which is okay. I’m a big boy, don’t get me wrong.”

Listening back to that part of the conversation after our interview made me feel dizzy. I can only speculate as to why Biden’s campaign agreed to this interview, but I assume the reasoning went something like this: If Biden disclosed to me, a person who stutters, that he himself still actively stutters, perhaps voters would cut him some slack when it comes to verbal misfires, as well as errors that seem more related to memory and cognition. But whenever I asked Biden about what appeared to be his present-day stuttering, the notably verbose candidate became clipped, or said he didn’t remember, or spun off to somewhere new.

I wondered if I reminded Biden of his old self, a ghost from his youth, the stutterer he used to be. He and I are about the same height. We happened to be wearing the exact same outfit that day: navy suit, white shirt, no tie. We both went to all-male prep schools, the sort of place where displaying any weakness is a liability.

As I listened to the recording of our interview, I remembered how I used to respond when people asked me about my stutter. I’d shut down. I’d try to change the subject. I’d almost always look away.

In early September, I got in touch with my high-school speech pathologist, Joseph Donaher, who practices at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. I hadn’t heard Donaher’s voice for almost 15 years. Immediately, I was transported back to the little windowless room in the hospital where we used to meet. Donaher was the first therapist—really the first person—who ever leveled with me. I can still see his face, the neutrality in his eyes on the day he looked at me square and said the sentence my friends and parents had avoided saying my entire life: You have a severe stutter.

Donaher and his colleagues try to help their patients open up about the shame and low self-worth that accompany stuttering. Instead of focusing solely on mechanics, or on the ability to communicate, they first build up the desire to communicate at all. They then share techniques such as elongating vowels and lightly approaching hard-consonant clusters, meaning just touching on the first sound in a word like stutter—the st—to keep the mouth and throat from tensing up and interfering with speech. The goal isn’t to be totally fluent but, simply put, to stutter better.

This evolution in treatment has been accompanied by a new movement to destigmatize the disorder, similar to the drive to view autism through a lens of “neurodiversity” rather than as a pathology. The idea is to accept, even embrace, one’s stutter. There are practical reasons for this: Research shows, according to Donaher, that the simple disclosure “I stutter” benefits both the stutterer and the listener—the former gets to explain what’s happening and ease the awkward tension so the latter isn’t stuck wondering what’s “wrong” with this person. Saying those two words is harder than it seems. “I’m working with people who spend their whole lives and are never able to disclose it,” Donaher told me.

Eric S. Jackson, an assistant professor of communicative sciences and disorders at NYU, told me he believes that Biden’s eye movements—the blinks, the downward glances—are part of his ongoing efforts to manage his stutter. “As kids we figure out: Oh, if I move parts of my body not associated with the speech system, sometimes it helps me get through these blocks faster,” Jackson, a stutterer himself, explained. Jackson credits an intensive program at the American Institute for Stuttering, in Manhattan, with bringing him back from a “rock bottom” period in his mid-20s, when he says his stutter kept him from meeting women or speaking up enough to reach his professional goals. Afterward, Jackson went all in on disclosure: Every day for six months, he stood up during the subway ride to and from work and announced that he was a person who stutters. “I had this new relationship with my stuttering—I was like Hercules,” he told me. At 41, Jackson still stutters, but in conversation he confidently maintains eye contact and appears relaxed. He wishes Biden would be more transparent about his intermittent disfluency. “Running for president is essentially the biggest stage in the world. For him to come out and say ‘I still stutter and it’s fine’ would be an amazing, empowering message.”

Occasionally, Biden has used present-tense verbs when discussing his stutter. “I find myself, when I’m tired, cuh-cuh-catching myself, like that,” he said during a 2016 American Institute for Stuttering speech. Biden has used the phrase we stutterers at times, but in most public appearances and interviews, Biden talks about how he overcame his speech problem, and how he believes others can too. You can watch videos posted by his campaign in which Biden meets young stutterers and encourages them to follow his lead. They’re sweet clips, even if the underlying message—beat it or bust—is out of sync with the normalization movement.

Emma Alpern is a 32-year-old copy editor who co-leads the Brooklyn chapter of the National Stuttering Association and co-founded NYC Stutters, which puts on a day-long conference for stuttering destigmatization. Alpern told me that she’s on a group text with other stutterers who regularly discuss Biden, and that it’s been “frustrating” to watch the media portray Biden’s speech impediment as a sign of mental decline or dishonesty. “Biden allows that to happen by not naming it for what it is,” she said, though she’s not sure that his presidential candidacy would benefit if he were more forthcoming. “I think he’s dug himself into a hole of not saying that he still stutters for so long that it would strike people as a little weird.”

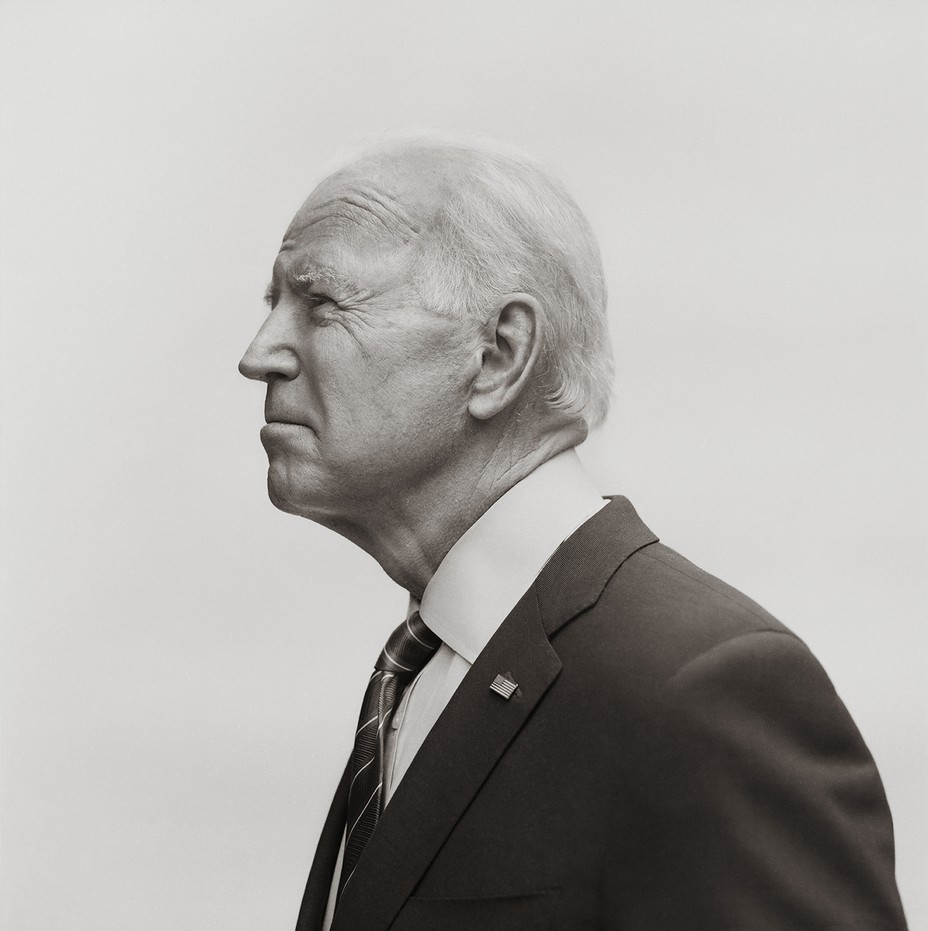

Biden has presented the same life story for decades. He’s that familiar face—Uncle Joe. He was born 11 months after Pearl Harbor and grew up in the last era of definitive “good guys” and “bad guys.” He’s the dependable guy, the tenacious guy, the aviators-and-crossed-arms guy. That guy doesn’t stutter; that guy used to stutter.

“My dad taught me the value of constancy, effort, and work, and he taught me about shouldering burdens with grace,” Biden writes in the first chapter of his 2007 memoir, Promises to Keep. “He used to quote Benjamin Disraeli: ‘Never complain. Never explain.’ ”

Stephen Colbert launches across the Ed Sullivan Theater stage, as if from a pinball spring. It’s early September, and his Late Show taping is about to begin. To warm up, he takes a few questions from the studio audience. Someone asks what he’d want in a potential new president. “Empathy?” Colbert deadpans. “A soul?”

Colbert tapes in Midtown Manhattan on the same stage where the Beatles made their American television debut 55 years ago, when Joe Biden was a mere 22. Biden struts out to a standing ovation and throws up his hands in amazement: For me? A brief “Joe! Joe! Joe!” chant erupts.

At first, Colbert lobs softballs, and Biden touches on the key parts of his 2020 stump speech: Why voters must stand up to the existential threat of Trumpism and how the Charlottesville, Virginia, white-supremacist rally crystallized his decision to run. Then Colbert goes for it.

“In the last few weeks, you’ve confused New Hampshire for Vermont; said

Bobby Kennedy and MLK were assassinated in the late ’70s; assured us, ‘I am not going nuts.’ Follow-up question: Are you going nuts?”

“Look, the reason I came on the Jimmy Kimmel show was because—”

The audience howls. Biden flashes a flirty smile. Colbert adjusts his glasses, sticks his pen in his mouth, and nods in approval. The joke was probably canned, but Biden landed it.

Colbert continues to press him about accuracy issues in his storytelling. The studio audience is silent; I’m watching from the balcony and can hear the theater’s air-conditioning humming overhead.

“I-I-I-I-I don’t get wrong things like, uh, ya know, there is a, we, we should lock kids up in cages at the border. I mean, I don’t—” People applaud before Biden can finish.

When the interview is over, Biden receives a second standing ovation. He peers up toward the rafters, using his hand as a visor against the bright lights. A white spotlight follows him offstage. Several minutes later, he glides through the stage door and out onto West 53rd Street. People call to him from the sidewalk. “Joe! Joe Biden!” He climbs into the back of an idling black SUV, and the doors

clunk close.

I follow Biden for a couple of days while he campaigns in New Hampshire. His town halls have a distinctly Norman Rockwell vibe. One takes place in the middle of the day on the third floor of a former textile mill, another on a stretch of grass as the wind whips off the Piscataqua River. His crowds are predominantly older, filled with people who stand for the Pledge of Allegiance and wait patiently to ask questions. After he speaks, Biden typically walks offstage to Bruce Springsteen’s “We Take Care of Our Own,” then saunters down the rope line for handshakes and hugs and selfies. One voter after another tells me they’re unaware of Biden’s stutter. “Knowing that he has had something like that to deal with and overcame it, as well as other really sad things that have happened—it just makes me like him more,” says 70-year-old Grace Payne.

Back in New York, I start to wonder if I’m forcing Biden into a box where he doesn’t belong. My box. Could I be jealous that his present stutter is less obvious than mine? That he can go sentences at a time without a single block or repetition? Even the way I’m writing this piece—keeping Biden’s stammers, his ums and pauses, on the page—seems hypocritical. Here I am highlighting the glitches in his speech, when the journalistic courtesy, convention even, is to edit them out.

I spend weeks watching Biden more than listening to him, trying to “catch him in the act” of stuttering on camera. There’s one. There’s one. That was a bad one. Also, I start stuttering more.

In September, before the third Democratic debate, in Houston, I called Michael Sheehan, a Washington, D.C.–area communications coach whose company website boasts clients ranging from Nike to the Treasury Department. Sheehan worked with President Bill Clinton while he was in office and began consulting on and off for Biden in 2002, when he was in the Senate. On the day we spoke, he was in Wilmington, Delaware, doing debate prep with Biden.

Sheehan and I traded stories of daily indignities—he stutters too. “I remember exactly where the deli was; it was on 71st and First Avenue,” he said with an ache in his voice. He lamented the interventionists, the people who volunteer, “ ‘You know, why don’t you speak more slowly?’ I always want to say ‘Holy shit! Why didn’t I think of that? Thank you!’ ”

Sheehan’s own stutter improved, but didn’t fully go away, when he took up speech and debate in high school. This eventually led him to the theater, which is a common, if surprising, place where some stutterers find that they’re able to speak with relative ease. Taking on a character, another voice, the theory goes, relies on a different neural pathway from the one used in conversation. Many successful actors have battled stutters—Samuel L. Jackson, Bruce Willis, Emily Blunt, James Earl Jones. In 2014, Jones, whose muscular baritone is the bedrock of one of the most quoted lines in film history, told NPR that he doesn’t use the word cured to describe his apparent fluency. “I just work with it,” he said.

Sheehan was extremely careful with the language he used to describe Biden’s speech patterns—“I can’t say it’s a stutter”—though he noted his friend’s habit of abruptly changing directions mid-sentence. “I do hear those little pauses, but I really don’t hear the stuff that you would hear from me or I would hear from you,” he said. A few minutes into our conversation, he choked up while discussing Biden’s tenderness toward young stutterers. “Sometimes I feel when he goes a little long on a speech, he’s just making up for lost time, you know?”

Sheehan told me about a night when he came home with his wife and saw the answering-machine light blinking: “Hey, Michael, it’s Joe Biden. I just was watching The King’s Speech with my granddaughter, and I just thought I’d give you a call, because it made me think of you. Goodbye!” He says the message felt like a secret fraternity handshake: “You and I have both been there, and only people in that society know what that is about.”

In Biden’s office, the first time I bring up his current stuttering, he asks me whether I’ve seen The King’s Speech. He speaks almost mystically about the award-winning 2010 film. “When King George VI, when he stood up in 1939, everyone knew he stuttered, and they knew what courage it took for him to stand up at that stadium and try to speak—and it gave them courage … I could feel that. It was that sinking feeling, like—oh my God, I remember how you felt. You feel like, I don’t know … almost like you’re being sucked into a black hole.”

Presidential candidates usually don’t speak about their bleakest moments, certainly not this viscerally. It resembles the way Biden writes in his memoir about the aftermath of the 1972 car accident that killed his first wife and young daughter and critically injured his two sons, Beau and Hunter: “I could not speak, only felt this hollow core grow in my chest, like I was going to be sucked inside a black hole.”

A few weeks later, I ask Jill Biden what she remembers about sitting next to her husband during the movie. “It was one of those moments in a marriage where you just sort of understand without words being spoken,” she says.

As he watched The King’s Speech, Biden accurately guessed that the screenwriter, David Seidler, was a stutterer. “He showed me a copy of a speech they found in an attic that the king had actually used, where he marks his—it’s exactly what I do!” Biden tells me, his voice lifting. “My staff, when I have them put something on a prompter—I wish I had something to show you.”

He pulls out a legal pad and begins drawing diagonal lines a few inches apart, as if diagramming invisible sentences: x words, breath, y words, breath. “Because it’s just the way I have—the, the best way for me to read a, um, a speech. I mean, when I saw The King’s Speech, and the speech—I didn’t know anybody who did that!”

Biden is running for president on a simple message: America is not Trump. I’m not Trump. I’ll lead us out of this. With every new debate, with every new “gaffe,” the media continue to ask whether Biden has the stamina for the job. And with every passing month, his competitors—namely Senator Elizabeth Warren and South Bend, Indiana, Mayor Pete Buttigieg—have gained on him in the polls.

A stutter does not get worse as a person ages, but trying to keep it at bay can take immense physical and mental energy. Biden talks all day to audiences both small and large. In addition to periodically stuttering or blocking on certain sounds, he appears to intentionally not stutter by switching to an alternative word—a technique called “circumlocution”—which can yield mangled syntax. I’ve been following practically everything he’s said for months now, and sometimes what is quickly characterized as a memory lapse is indeed a stutter. As Eric Jackson, the speech pathologist, pointed out to me, during a town hall in August Biden briefly blocked on Obama, before quickly subbing in my boss. The headlines after the event? “Biden Forgets Obama’s Name.” Other times when Biden fudges a detail or loses his train of thought, it seems unrelated to stuttering, like he’s just making a mistake. The kind of mistake other candidates make too, though less frequently than he does.

During his 2016 address at the American Institute for Stuttering, Biden told the room that he’d turned down an invitation to speak at a dinner organized by the group years earlier. “I was afraid if people knew I stuttered,” he said, “they would have thought something was wrong with me.”

Yet even when sharing these old, hard stories, Biden regularly characterizes stuttering as “the best thing that ever happened” to him. “Stuttering gave me an insight I don’t think I ever would have had into other people’s pain,” he says. I admire his empathy, even if I disagree with his strict adherence to a tidy redemption narrative.

In Biden’s office, as my time is about to run out, I bring up the fact that Trump crudely mocked a disabled New York Times reporter during the 2016 campaign. “So far, he’s called you ‘Sleepy Joe.’ Is ‘St-St-St-Stuttering Joe’ next?”

“I don’t think so,” Biden says, “because if you ask the polls ‘Does Biden stutter? Has he ever stuttered?,’ you’d have 80 to 95 percent of people say no.” If Trump goes there, Biden adds, “it’ll just expose him for what he is.”

I ask Biden something else we’ve been circling: whether he worries that people would pity him if they thought he still stuttered.

He scratches his chin, his fingers trembling slightly. “Well, I guess, um, it’s kind of hard to pity a vice president. It’s kind of hard to pity a senator who’s gotten six zillion awards. It’s kind of hard to pity someone who has had, you know, a decent family. I-I-I-I don’t think if, now, if someone sits and says, ‘Well, you know, the kid, when he was a stutterer, he must have been really basically stupid,’ I-I-I don’t think it’s hard to—I’ve never thought of that. I mean, there’s nobody in the last, I don’t know, 55 years, has ever said anything like that to me.”

He slips back into politician mode, safe mode, Uncle Joe mode: “I hope what they see is: Be mindful of people who are in situations where their difficulties do not define their character, their intellect. Because that’s what I tell stutterers. You can’t let it define you.” He leans across the desk. “And you haven’t.” He’s in my face now. “You can’t let it define you. You’re a really bright guy.”

He’s telling me, in essence, that my stutter doesn’t matter, which is what I want to tell him right back. But here’s the thing: Most of the time, Biden speaks smoothly, and perhaps he sincerely does not believe that he still stutters at all. Or maybe Biden is simply telling me the story he’s told himself for several decades, the one he’s memorized, the one he can comfortably express. I don’t want to hear Biden say “I still stutter” to prove some grand point; I want to hear him say it because doing so as a presidential candidate would mean that stuttering truly doesn’t matter—for him, for me, or for our 10-year-old selves.

Now his aide is knocking, trying to get him out of the room. I push out one more question, asking what he saw reflected in that bedroom mirror as a kid.

He goes off into a different boyhood story about standing against a stone wall and talking with pebbles in his mouth, some oddball way to MacGyver fluency. I do the thing stutterers hate most: I cut him off. “What did that person look like?”

Biden stops. “He looked happy,” he says. “You know, I just think it looked like he’s

in control.”

This article appears in the January/February 2020 print edition with the headline “Why Won’t He Just Say It?”