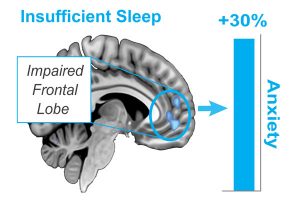

Studies in healthy human volunteers have shown how a sleepless night can increase anxiety levels by 30%. In some participants just one night of disturbed sleep resulted in levels of anxiety the next day that were above the threshold for common anxiety disorders. The research, carried out by scientists at the University of California (UC), Berkeley, found links between sleep loss-related anxiety and impaired activity in specific areas of the brain, and also indicated that slow-wave, non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep has an anxiolytic effect on brain networks.

“We have identified a new function of deep sleep, one that decreases anxiety overnight by reorganizing connections in the brain,” said study senior author Matthew Walker, PhD, a UC Berkeley professor of neuroscience and psychology. “Deep sleep seems to be a natural anxiolytic (anxiety inhibitor), so long as we get it each and every night.”

The studies, published in Nature Human Behaviour, provide one of the strongest neural links between sleep and anxiety to date. They also point to sleep as a natural, non-pharmaceutical remedy for anxiety disorders, which have been diagnosed in some 40 million adults in the United States. Anxiety disorders are also on the increase among children and teenagers.

“Our study strongly suggests that insufficient sleep amplifies levels of anxiety and, conversely, that deep sleep helps reduce such stress,” said study lead author Eti Ben Simon, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the Center for Human Sleep Science at UC Berkeley. The team’s research is reported in a paper titled, “Overanxious and underslept.”

Sleep disruption is a recognized feature of all anxiety disorders, and has been linked with the development and progression of such anxiety disorders, the authors wrote. “Testament to this link, sleep disturbance is present across the full axis of major anxiety disorders, including post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder, suggesting trans-diagnostic applicability.”

Given this association, the UC Berkeley team set out to answer some key questions. They devised experiments to investigate the neural basis of why and how a lack of sleep amplifies anxiety, and to determine whether different phases of sleep might be able to ameliorate anxiety associated with insufficient sleep. Another study was carried out to determine whether subtle changes in sleep patterns within an individual from one night to the next affected day-to-day anxiety levels.

“Indeed, following sleep deprivation, 50% of our experimental participants expressed levels of anxiety that exceeded the clinical threshold described in typical anxiety disorders … Our experimental studies demonstrate that, within this interaction, sleep loss can causally and directionally instigate high levels of anxiety in individuals who were otherwise nonclinically anxious when sleep-rested.” Walker added, “Without sleep, it’s almost as if the brain is too heavy on the emotional accelerator pedal, without enough brake.”

The results also showed that after a full night of sleep, during which participants’ brain waves were measured via electrodes placed on their heads, anxiety levels dropped significantly, especially for those who experienced more slow-wave NREM sleep. During NREM sleep neural oscillations become highly synchronized, and heart rates and blood pressure drop. “Deep sleep had restored the brain’s prefrontal mechanism that regulates our emotions, lowering emotional and physiological reactivity and preventing the escalation of anxiety,” Simon noted.

Beyond gauging the sleep-anxiety connection in the 18 original study participants, the researchers replicated the results in a study of another 30 participants. Across all the participants, the results again showed that those who got more deep sleep overnight experienced the lowest levels of anxiety the next day.

In addition to the lab experiments, the researchers also conducted an online study in 280 people of all ages, who were questioned about how both their sleep and anxiety levels changed over four consecutive days. The results showed that changes in the amount and quality of sleep the participants got from one night to the next predicted how anxious they would feel the next day. Even subtle changes in sleep affected their anxiety levels. “… ecologically relevant night-to-night variability in sleep within individuals predicted consequential day-to-day changes in subjective anxiety state—an effect that was independent of alterations in mood as well as in trait,” the authors wrote. “These micro-longitudinal experiments not only corroborate the results of the in-laboratory experiment manipulation of acute total sleep deprivation, but demonstrate that subtle alterations in nightly sleep quality are sufficient to result in consequential next-day changes in anxiety.”

The investigators say the finding that even modest reductions in sleep quality impact on anxiety levels the next day is relevant, given what they describe as “the continued erosion of sleep time in developed nations,” and the “high prevalence and economic health burden of anxiety disorders in these same countries.” And given that 70–80% of patients with anxiety disorders report poor sleep, disturbed sleep might represent an “underappreciated factor” in the increasing rates of anxiety disorders. “Shifting to prevention, our findings suggest that even modest improvements in sleep quality may have the potential to reduce subjective anxiety, serving as a non-pharmacological prophylactic,” the team concluded.

“People with anxiety disorders routinely report having disturbed sleep, but rarely is sleep improvement considered as a clinical recommendation for lowering anxiety,” Simon stated. “Our study not only establishes a causal connection between sleep and anxiety, but it identifies the kind of deep NREM sleep we need to calm the overanxious brain.”

On a societal level, “the findings suggest that the decimation of sleep throughout most industrialized nations and the marked escalation in anxiety disorders in these same countries is perhaps not coincidental, but causally related,” Walker added. “The best bridge between despair and hope is a good night of sleep.”