by Lucien Holness

The late 1830s were an increasingly violent period for African Americans in northern cities. Throughout the decade, blacks faced a greater risk of being kidnapped into slavery and growing assaults and mob violence committed by whites. To many African Americans, the state and antislavery societies did not provide adequate protection. In New York City, black abolitionist David Ruggles called for African Americans to defend their own communities from kidnappers through the formation of vigilance committees, noting that “self-defense is the first law of nature.”[1]

Many Americans view self-defense as a natural right. However, African Americans have a long history of being denied the right to armed protection in a society that has sought to undergird white supremacy.

African American Self-Defense Under Slavery

The racialization of armed self-defense can be traced to the earliest days of American history when blacks were denied any right to self-protection that could present a blow against slavery and racism. In the early nineteenth century, court cases such as State v. Mann (1824) began to set legal precedent that denied slaves the right to defend themselves in several circumstances, such as running away from a master.[2] During this same period, northern free blacks witnessed the elimination of many legal rights by state and federal legislators—one of those being the right to serve in the state militia. To most whites, legally sanctioning black men’s right to take up arms in defense of themselves represented a marker of equal citizenship, which many were not willing to give to African Americans.

By the 1840s, some black abolitionists became pessimistic about the possibility of racial justice in the United States. In a controversial speech before the Nation Negro Convention held at Syracuse in 1843, black minister Henry Highland Garnet called on slaves to “use every means, both moral, intellectual, physical” to escape slavery.[3] Many black northerners were hesitant in advocating the use of armed forced either by slaves or free African Americans in ending black bondage.

The Fight for Black Self-Defense and Freedom: The Civil War Era

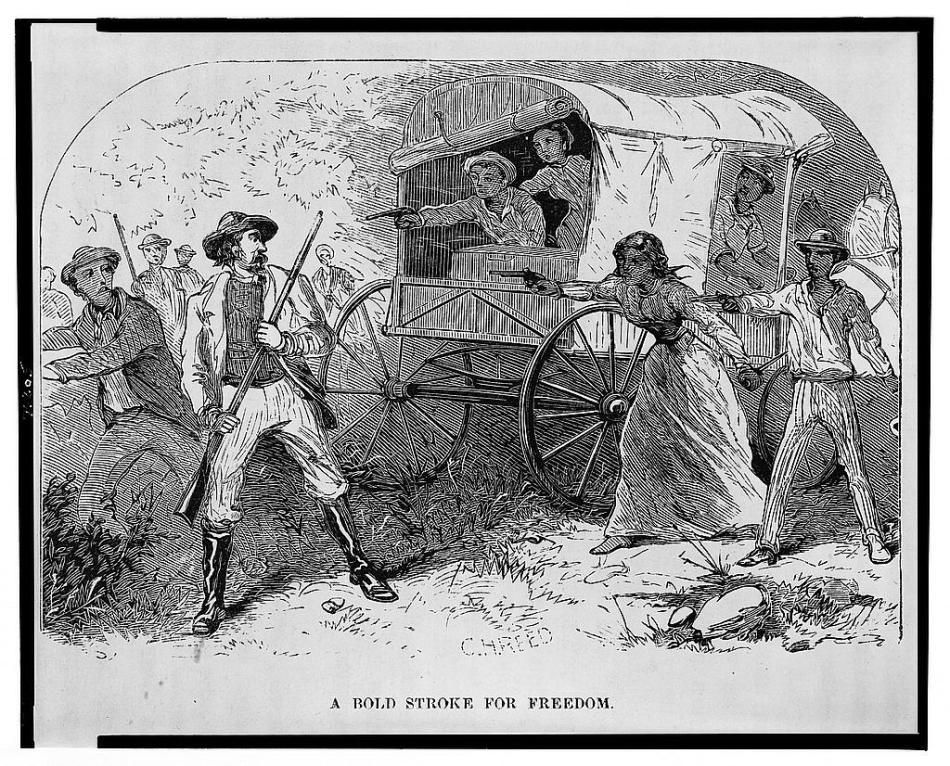

During the 1850s, there was a growing desire among African Americans to take up arms. This sentiment was inspired in part by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, which placed free blacks throughout the north at an even greater risk of being captured into slavery. Jermain Loguen, a black minister in the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, advocated that blacks use force to “smite down Marshals and Commissioners” who were charged with enforcing the new law. He compared black resistance to the actions of the Founding Fathers. At an 1851 celebration commemorating the end of slavery in the British West Indies, New York Reverend Peter Gardner expressed his support for African Americans’ desire to obtain knowledge of “military science.” In a June 1854 editorial in Fredrick Douglass’ Paper, William Watkins defended African Americans’ right to self-defense, declaring that blacks “should certainly kill the man who would dare lay his hand on us, or on our brother, or sister, to enslave us.”[4] Throughout the north, many African Americans viewed armed self-defense and the right to take up arms as crucial in their fight against white supremacy.

When civil war erupted, many African Americans sent letters to the War Department and their respective state governments offering their military service to the Union Army. A Pittsburgh commander of the Hannibal Guards—a black military company—wrote to a militia commander of West Pennsylvania, General James S. Negley, offering his group’s military service to fight “against the tyranny of slavery.” Rufus Sibbs Jones, a brickmaker and captain of the Fort Pitt Cadets of Pittsburgh, wrote in the spring of 1862 to the Secretary of War that the members of his company were ready to fight, already trained in military discipline. He also pledged that he could recruit two-hundred additional men within a month to supplement the ranks.

Many black men believed that military service offered an avenue to citizenship rights. Some prospective black soldiers had family members still enslaved in the South. However, black offers to serve were initially rejected by the Union Army, as white officials sought to make the preservation of the Union—rather than emancipation and black rights—the central war aim. White attitudes towards blacks serving in the army began to change as casualties mounted, reducing manpower, which the army experienced as a series of misfortunes on the battlefield. Lincoln did not authorize the use of black troops until January 1863 when he signed the Emancipation Proclamation.[5]

Despite African Americans’ crucial contributions to the Union victory, many whites were troubled by the presence of armed African Americans as black soldiers returned home with their issued weapons or arms captured in war. After the Civil War, many southern states passed a series of acts regulating the labor and behavior of freedpeople known as black codes. Some of these laws placed strict regulations and prohibitions on black access to and ownership of firearms. In the late 1860s, white supremacists established vigilante organizations—such as the Ku Klux Klan, ’76 Association, Knights of the White Camelia, and White Brotherhood—across the South with the goal of subjugating former slaves. The targets of these attacks were successful, economically independent African American landowners and entrepreneurs as well as schools, lodges, and churches, which represented black progress and were centers of political organization. Across the South there were waves of terror and race riots, as whites sought to stifle the political, economic, and social gains African Americans achieved during Reconstruction and return to power in state and local governments.

Many black Americans believed that the right to armed self-defense was crucial to protecting their communities, which they voiced by sending petitions to Congress protesting racially discriminatory state laws that regulated their access to guns. African Americans worked to ensured that Klansmen and other white terror groups would think twice about attacking their communities. In June 1868, a white vigilante group commenced an attack on the black community outside Carthage, Mississippi, when it was discovered that the African Americans were well armed, raising the possibility of deadly resistance and retaliation. While the end of Reconstruction in 1877 represented a political triumph of white supremacy in the South, the use of armed self-defense continued to serve an important role in the black freedom struggle.[6]

Armed Black Self-Defense in Segregation

Historians have described the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century as the nadir of race relations in the United States. New laws were established to support and enforce a system of Jim Crow and disenfranchise black men. When these tactics were not completely successful in subordinating African Americans and suppressing black rights, whites turned to violence—one of the most horrific and widely used forms being lynching. In response to this epidemic of racial violence and terror, anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett wrote in her 1892 expose on lynching, Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All its Phases, that “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses to give.”

Despite the call among black leaders to arm themselves in self-defense, most African Americans recognized the risk of an open armed conflict with white supremacy. W.E.B. Dubois, a professor of economics and history at Atlanta University and one of the foremost black intellectuals, wrote in his Souls of Black Folk about the possible escalation of violence if blacks adopted an organized, large-scale armed conflict against white supremacy. Therefore, most instances of self-defense during this period were personal rather than consciously political. They were also a local response to white terror rather than part of a national movement.[7]

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s represented a crucial turning point in the black freedom struggle. White supremacists in the Jim Crow South relied on fear and intimidation to maintain their economic and political control over the region. The struggle for racial justice was not only a movement to challenge white power, but a fight to overcome the fear of racial terrorism and assert the right of self-defense. The use of armed resistance in defense of the movement was an essential tactic used alongside nonviolence in the black freedom struggle.

As the Civil Rights movement gained momentum and African Americans began to achieve some notable political successes, there was an increase in racial terror orchestrated by the Ku Klux Klan. In response, the Deacons for Defense and Justice, an armed group organized in Mississippi and Louisiana, was established in 1964 to protect civil rights activists and leaders. During the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee’s 1965 voter registration drive in Lowndes County, Alabama—a place so violent it was called “Bloody Lowndes”—black people fortified their homes and organized in defense of their community. At night, local people kept shotguns in their bedrooms to protect against nightriders; during the day they carried weapons as they worked to register people to vote.[8]

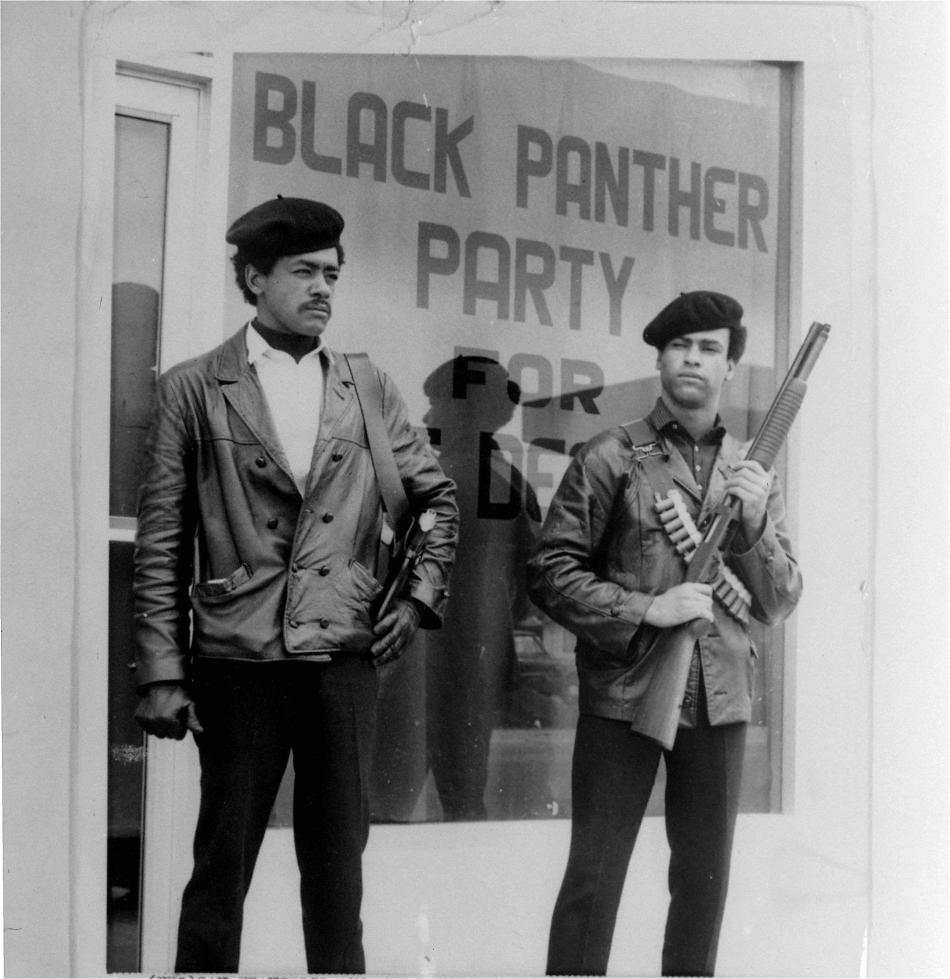

The struggle for armed self-defense was not limited to the southern Civil Rights Movement. Many black communities in the north and west faced decades of police repression and brutality. Two Merritt College students in Oakland, California—Huey Newton and Bobby Seale—inspired by a growing sentiment of Black Power, formed the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense (BPPSD) in response to police violence. Their Ten Point Program, first publicized in May 1967, made the right to bear arms a priority, declaring that the Second Amendment gave blacks the right to defend themselves against racist police oppression and brutality. On May 2, 1967, thirty black members of the BPPSD—men and women—made their way inside the California State Capitol building, guns loaded, expressing their opposition to lawmakers about the prospect of new gun control measures, believing that these actions would leave African Americans powerless against police violence. The actions of the BPPSD, along with the violent black urban rebellions sweeping the nation that summer, produced an immediate backlash from legislators and the public, resulting in the passage of a number of gun-control measures in California and the nation’s capital.[9]

Contemporary Gun Debates and Race

A study of African Americans’ long history of armed self-defense shows that controversial legal doctrines, such as Stand Your Ground, first took root in black communities seeking to defend themselves against white terror and in defense of black lives. However, race has—and continues to—play a central role surrounding who can exercise armed self-defense. For example, civil rights activists have pointed to racial bias, as whites who killed blacks were more likely to be found justified in their killing in states where Stand Your Ground was legal. According to an investigative report, “In non-Stand Your Ground states, whites were 250 percent more likely to be found justified in killing a black person than a white person who kills another white person; in Stand Your Ground states, that number jumps to 354 percent.”[10]

In an era of mass shootings and in the racially polarized age of Trump, incidents such as Charlottesville have produced renewed interested and debate among African Americans over the use of self-defense.[11] However, some African Americans have been cautious in issuing calls to defend themselves, recognizing that this right has not been applied equally, taking into account racial bias in the criminal justice system.[12] The history of black gun rights is a complicated story, one that has been used both to challenge and to reaffirm white supremacy.

Lucien Holness is a PhD candidate in African American history at the University of Maryland. His research interests include slavery and abolition as well as race and black politics in nineteenth century America. Lucien’s dissertation “Between North and South, East and West: The Anti-Slavery Movement in Southwestern Pennsylvania” frames southwestern Pennsylvania as a borderland between slavery and freedom and a crossroad between abolitionists in the East and Old Northwest. By shifting the center of antislavery politics and discussions about race from Philadelphia to southwestern Pennsylvania, Lucien’s dissertation uncovers a political culture that had important consequences for the black freedom struggle statewide and nationally. He holds an MA in history from Villanova University.

Lucien Holness is a PhD candidate in African American history at the University of Maryland. His research interests include slavery and abolition as well as race and black politics in nineteenth century America. Lucien’s dissertation “Between North and South, East and West: The Anti-Slavery Movement in Southwestern Pennsylvania” frames southwestern Pennsylvania as a borderland between slavery and freedom and a crossroad between abolitionists in the East and Old Northwest. By shifting the center of antislavery politics and discussions about race from Philadelphia to southwestern Pennsylvania, Lucien’s dissertation uncovers a political culture that had important consequences for the black freedom struggle statewide and nationally. He holds an MA in history from Villanova University.

* * *

Our collected volume of essays, Demand the Impossible: Essays in History As Activism, is now available on Amazon! Based on research first featured on The Activist History Review, the twelve essays in this volume examine the role of history in shaping ongoing debates over monuments, racism, clean energy, health care, poverty, and the Democratic Party. Together they show the ways that the issues of today are historical expressions of power that continue to shape the present. Also, be sure to review our book on Goodreads and join our Goodreads group to receive notifications about upcoming promotions and book discussions for Demand the Impossible!

* * *

We here at The Activist History Review are always working to expand and develop our mission, vision, and goals for the future. These efforts sometimes necessitate a budget slightly larger than our own pockets. If you have enjoyed reading the content we host here on the site, please consider donating to our cause.

Notes

[1] “Founding the New York Committee of Vigilance: David Ruggles to Editor, New York Sun, [July 1836]” in The Black Abolition Papers: Vol. III: The United States, ed. C. Peter Ripley (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 168-180.

[2] Christopher B. Strain, Pure Fire: Self-Defense as Activism in the Civil Rights Era (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2005), 8-9.

[3] “An Address to the Slaves of the United States of America,” 1843, reprinted in Garnet, A Memorial Discourse by Rev. Henry Highland Garnet (Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1865), 44-51.

[4] Anonymous Observer, “For Frederick Douglass’ Paper, Frederick Douglass Paper, September 4, 1851; William J. Watkins, “Editorial by William J. Watkins,” in The Black Abolitionist Papers: Vol. IV: The United States, ed. C. Peter Ripley (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), 227-229.

[5] James McPherson, The Negro’s Civil War: How American Blacks Felt and Acted During the War for the Union (1965 repr., New York: Vintage Books, 1993), 19-20; Captain of a Black Militia Company to the Secretary of War, in Ira Berlin et al., eds. Freedom A Documentary History of Emancipation, ser. 2: The Black Military Experience (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982), 83-84; David Williams, I Freed Myself: African American Self-Emancipation in the Civil War Era (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2014), 68-69, 97-106.

[6] Nicholas Johnson, Negroes and the Gun: The Black Tradition of Arms (Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2014), 78-81; Steven Hahn, A Nation Under Our Feet: Black Political Struggles in the Rural South from Slavery to the Great Migration (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 280-281.

[7] Nicholas Johnson, Negroes and the Gun, 151-153.

[8] Charles E. Cobb Jr., This Nonviolent Stuff’ll Get You Killed: How Guns Made the Civil Rights Movement Possible (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 182-183.

[9] Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (University of California Press, 2013), 72; Adam Winkler, “The Secret History of Guns,” The Atlantic Magazine (September 2011) ttps://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2011/09/the-secret-history-of-guns/308608/.

[10] https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/frontline/article/is-there-racial-bias-in-stand-your-ground-laws/

[11] https://www.npr.org/2018/03/31/598503554/african-americans-guns-and-trump ; https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/in-response-to-racist-violence-more-african-americans-look-to-bear-arms

[12] https://www.npr.org/2015/04/02/396869889/more-african-americans-support-carrying-legal-guns-for-self-defense

Very well written.

LikeLike