nyctwigg: Ah, there you are; a Skype username you created while working in New York for a month. And here I am, trying to call someone yet absent-mindedly pulling up your profile. In the tiny square picture icon, you are there in your blue T-shirt, leaning over the table and smiling at the camera. Next to your name it says, “Hear me now”.

That drove me mad; you’d sit there and repeat, “Hear me now? Hear me now?” A deliberately annoying mantra, because you knew I could hear you perfectly well. I would hang up and redial to a laughing you and we’d catch up, but today I sit and stare, wishing I could conjure up that annoying voice again. Even just once.

I press the little video camera icon to see if I can get through. But it doesn’t even give me the satisfaction of ringing. Instead the screen says “ended” and the call hangs itself up. Guess that’s fair. That’s when I realise it says “offline”. “nyctwigg offline”. Also fair. I should delete your account … and your phone number, email address and all sorts of other aspects of your online life. I sit and wonder if other people you were connected to have deleted your profile. And I stare out the window wondering if I should try to call you again.

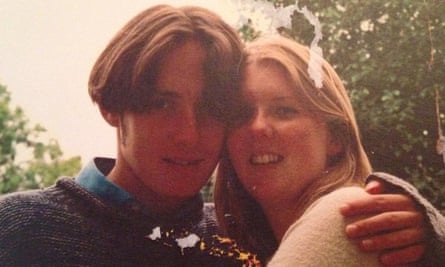

My husband, Iain, and I met at school when we were 17, dated in the sixth form, went our separate ways at university, then got back together and married in a flurry of excitement in 2008. Iain worked for the Foreign and Commonwealth Office so we lived, worked and adventured together for seven years in Delhi and Geneva. In October 2013, Iain was diagnosed with a brain tumour, and on 7 December 2014, he died in our bed at home. On that morning, my husband, our hoped for family and my future roadmap of work and travel for the next 40 years, all vanished in one shuddering breath. We were both 33.

Six months along this single-track pathway, I’m repeatedly aware I have to rebuild and reshape my life – a life I can’t remember distinct from Iain. If your partner dies, a lot of admin also comes your way. And, these days, people die a digital death alongside their physical one, which creates a whole new world of admin that didn’t pass the radar of grieving widows 50 years ago. Those 20th-century widows would have had a box of love letters and a few hard copy photos; I have Facebook messages, professional videos on YouTube, personal videos on my iPhone, email histories, recorded Skype chats, WhatsApp conversations, text messages and digital photos – photos galore. And all this from a marriage with someone who never really liked spending time online. He set out his stall at 18 announcing that he wouldn’t be getting a mobile phone because they “seem pretty annoying, I doubt they’ll catch on”.

I’ve found at least one blog that tries to make sense of it all. The Digital Beyond, which offers a “go-to source for archival, cultural, legal and technical insights, to help you predict and plan for the future of your online content”. Along with “scatter tubes” – tubes with a perforated lid for transporting and scattering ashes – and bespoke jewellery made from ashes, it’s another blossoming industry I never knew existed.

The blog lists 54 online companies that deal specifically with aspects of dying or, more commonly, the legacy of memories online. I’m slightly spooked by the number of websites that help you send posthumous messages to your friends and relatives. ToLovedOnes, for example, will send letters after your death, calculating the dates they are posted “with 95% accuracy from public records”. Which just leaves me worrying about the 5% of people who receive the letters when their relative is still alive.

Knotify.me, meanwhile, is a free app that answers the question you never knew you had; “What happens to all my online accounts if I get amnesia, Alzheimer’s or if I leave this world?” It helps you set future notifications for your family or yourself, so “nothing of your digital life will be wasted”. Remembered Voices lets you record your voice and play it back to people after you’ve died, Cirrus Legacy stores digital assets in a single place online, so your executor can access them easily. That would have been helpful, in fact. Terry Pratchett was in the know – his recent death was announced in a series of tweets from his own account.

Just as we’re playing catch up with technology, the technology developers themselves are in the same position. Dying, understandably, didn’t feature highly in Facebook’s early risk registers. Which might be why it was in trouble recently for locking a grieving mother out of her teenage daughter’s Facebook account, despite having her daughter’s permission to use it.

When someone dies, Facebook tends to “memorialise” their account – freeze them so they can be viewed, but providing no access to past messages. I read that and panicked: I didn’t want that to happen, so grabbed my laptop and logged in urgently as Iain. Once in though, I wasn’t really sure what I wanted to do – it didn’t feel right reading personal messages to and from other people. They weren’t for me. If he’d left a box of letters, would I have read those? People store important letters, but online messages are kept just because we don’t press delete. Should I read his emails? I didn’t. But I read and reread our text message conversations, which lifted me up so high it felt like we were actually chatting. Then when I got to the end and there were no more, it was a bad, long fall from there. So I decided memorialising was OK.

Facebook also offended a fair number of bereaved people with its Year in Review clips, in which photographs that attracted the most comments were automatically selected to reappear on your timeline under the words “Here’s what your year looked like”. The problem was that for some, these were pictures of dead loved ones. And, however comforting photos and associated memories can be, out of the blue and at the wrong moment on your computer screen they can cause havoc if you are grieving.

The bereaved: an oversensitive minority population, you may think, but the numbers involved are bigger than you may realise. Based on Facebook’s growth rate, and the age breakdown of its users over time, probably 10 to 20 million people who created Facebook profiles have since died. Even if Facebook closed registration tomorrow, the number of deaths per year will continue to grow for decades, as the 2000-2020 school generations grow old. And the peak? Nasa physicist turned full-time cartoonist Randall Munroe estimates that if Facebook falls out of favour with young generations, as many social media sites do, the point at which there will be more users who have died than are living is around 2060. And if Facebook continues to thrive, that’s more like 2130.

In the hours and immediate few days after Iain died, I turned to the memorial website built overnight by a kind colleague to celebrate my man’s life. A bewildered and floundering group of Iain’s closest friends and family immersed ourselves in a world of photos and memories and words and purpose. Three days later, all within half an hour, the website went live, an email to the worldwide Foreign and Commonwealth Office workforce went out and I put a “global announcement” on Facebook. “Informing friends of the deceased”, 21st-century style. I changed my profile to black, shut my laptop and left the house; the internet did its thing – with speed, breadth and a rush of wildfire.

I hadn’t anticipated the outpouring of love from around the world. Within minutes there were messages from Japan, Pakistan, Chile … the inhabitants of our interconnected world, suddenly spinning inwards to be connected by shock and grief, then spinning out again to their own physical pockets around the world.

Today, one of the things I cherish most is an eight-second video of Iain telling me he loves me. There’s something about seeing him as if in real life and hearing his voice, that is just quite incredible. The only downside is that it’s far too short. And it’s all I’m going to get now. I wish I had more videos – they are by far the hardest thing to look at right now, but I sense that one day they will be some of the most precious things I have.

Otherwise a huge comfort and unity online has come from a network for younger people whose partners have died – Way (Widowed and Young). In the past month, I’ve got to know some of the 1,500 people in that group by seeing their biggest fears, their “smallest” achievements, their practical worries and their rallying strength posted online in a closed group. A sub-set of our society, normal people living normal lives that suddenly know tragedy and are thrust together in their confusion and loneliness and upset.

I don’t use the rest of Facebook so much now – I posted a positive few things early on and hadn’t expected so many instantaneous likes and messages saying I was “amazing”. It was too surreal to be told that when you’re barely able to hold a conversation in real life, and it made me feel strange. I’m certainly not going to start covering Facebook with the reality of the new world I have found myself living in since Iain’s death – people don’t go there to see the truth if it’s not pretty.

So, after I put my phone aside each evening and disconnect myself from my online communities, the moment just after my head hits the pillow is when the reality of my sadness becomes so stark. The moment I go from being exhausted to somehow feeling wide awake, when I feel so, so solo. I look over at Iain’s side of the bed and just his picture grins back at me. I poke my toe over the cold sheet and I wonder how it can be that he was right there, and now he’s not. I think about friends in their homes, with their favourite people breathing quietly beside them. I think of people listening out for babies in other rooms. For their children stirring. I want to say, “Imagine none of those people are in your house now, imagine that silence. And imagine it’s for always.” That’s how alone it feels.

As I lie there I wonder, have I fallen off the end of the world? I’ve discovered that when you cry while you’re lying on your back, your tears slide into your ears, which fill up and feel strange. I shake my head. And at some point I fall asleep. And then I wake up too early and feel the same.

As I take the commuter train, I look at everyone on their smartphones. I imagine there are others also scrolling through pictures of their families, just as I am with photos of Iain. I see a message from a lady, a new friend, whose husband also died of a brain tumour a few days before Iain – we’ve never met but have shared such a similarly traumatic story that we’re linked to each other now. As I go to reply, I’m aware that we’d never have connected if this had been 1915, not 2015.

Caroline Twigg has written a book to help bereaved children. Find out more at http://kck.st/1GL3UzI where she is raising money to illustrate and publish it

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion