North Korea holds a Tree Planting Day every March. The question is whether it helps regreen a largely denuded nation whose people face food shortages, deadly natural disasters and bitterly cold winters.

The public holiday began in 1946 when North Korea was under direct Soviet rule. Today, the state-sanctioned media still pays tribute to its claims of leafy success, sometimes with the participation of the “respected Supreme Leader.”

Even as new trees take root, subsistence logging and deforestation have an untold impact on the country’s soil quality and its ability to feed its people.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

“People cut down trees on a massive scale, both for fuel but also to clear room for farming,” said Benjamin Katzeff Silberstein, a Ph.D. candidate from the University of Pennsylvania who studies social control and surveillance in the North from Seoul, South Korea.

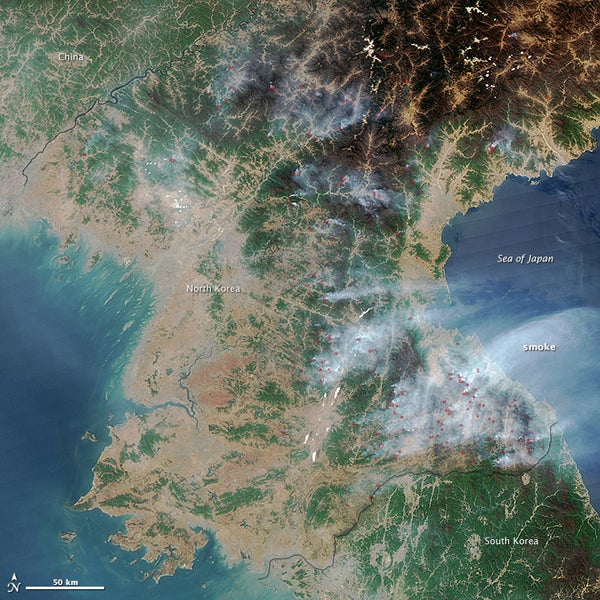

“You can see it when you’re standing by the border with North Korea, whether it’s in South Korea or in China,” he continued. “The side you’re on is just very lush. There are a lot of trees. But on the North Korean side, the hills are almost entirely bare.”

North Korea’s tree problem is one aspect of a bigger environmental crisis. The hermit state, known for its strident threats of nuclear war, is suffering from crippling drought and violent floods. Some experts suggest that those conditions, exacerbated by climate change, are pushing North Korean leader Kim Jong Un to the negotiating table to press President Trump for relief from economic sanctions (Climatewire, April 11).

The government of North Korea acknowledges that forest cover shrank sharply during a famine in the 1990s, going from 8.3 million hectares to 7.6 million hectares in just a few years. And a 2014 study by researchers at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and Gyeonggi Research Institute drew on satellite data collected by South Korea’s Environment Ministry to show that forests in the North are becoming more fragmented, with less contiguous tree cover.

That’s bad for North Korea’s wildlife, and it leads to depleted topsoil that’s unable to do the work of feeding North Korea’s population.

The lack of ground cover means there are no roots to anchor soil in place and keep it from running off into rivers and streams during extreme weather events. And while North Korea has the task of growing its food rather than trading for it, its geography makes that complicated. The Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations says that just 17% of its territory is suitable for agriculture.

“The country is mountainous with steep hill slopes, which in many places are deforested,” Bir Mandal, the FAO deputy representative in North Korea, wrote in an email to E&E News. “So, when a natural disaster occurs, it has the potential to cause much greater [disproportional] damage.”

The past decade has brought a succession of floods, droughts, storms and other extreme weather to North Korea, damaging crops and killing livestock. That’s resulted in landslides and land degradation, Mandal said. And also hunger. North Korea’s food supply fell by 9% last year, according to estimates by FAO and the World Food Programme.

Subsistence logging was once a problem for forests across the Korean Peninsula, and the Korean War of the early 1950s further damaged both countries’ trees.

“It was a denuded landscape,” remembered retired CIA officer William Brown, who spent time in South Korea in the 1950s and 1960s.

‘Very weird experience’

Forests in the South rebounded in the decades after the war thanks to aggressive reforestation policies and a crackdown on illegal logging. The country now has more forest cover than it did in the 1920s.

North Koreans, meanwhile, continued to harvest forests for fuel and to make fields during a succession of famines. Among these was the “Arduous March” of the 1990s, when the state’s food distribution system broke down. Some people resorted to eating bark.

The effect of the famine on North Korea’s landscape seems to have been uneven. Woonsup Choi, a researcher at UW Milwaukee, co-authored a study in 2017 using satellite data showing that the “Arduous March” had a small net effect on overall forest cover in North Korea, even though it caused a substantial amount of change in ground cover. During the 1990s and early 2000s, he said, some areas appear to have lost their forests, while others became overgrown—possibly as a result of mass deaths and abandonment of land formerly under cultivation.

Woonsup said any effort to interpret the findings for land changes would be speculative.

“I think this is a limitation of this data set,” he told E&E News. “Obviously it is almost impossible to go and see what’s going on.”

North Korea has on occasion allowed foreign researchers to see conditions inside the country, especially if it means gaining foreign expertise on an issue the regime cares about.

Deforestation and soil health are priorities for the regime. Kim is believed to have executed a deputy minister of construction and building materials after he opposed his crackdown on deforestation.

In 2013, Norman Neureiter, who was then director of the Center for Science, Technology and Security Policy for the American Association for the Advancement of Science, got clearance to bring a small delegation of scientists to Pyongyang for a two-day conference on deforestation and soil health. It was followed by site visits outside of the capital. He was allowed to bring 15 experts, and no more than five could be Americans.

“It was very nice,” said Neureiter, who is now a senior adviser at AAAS’s Center for Science Diplomacy. He remembered the venue—a fine building in the heart of Pyongyang with a big sign outside announcing it was happening—and 70 or 80 of North Korea’s top scientists in attendance. “It was really a well-done event.”

But Margaret Palmer, director of the University of Maryland’s National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center, called it “a very weird experience.”

“What we felt we needed when we went over, and what we assumed we’d be able to do, is to talk to them informally and in a frank way,” said Palmer. “‘Tell us about your problems, tell us about what kinds of things you can do, and we can give you advice.’"

Instead, they were treated to a “show” of presentations, she said, often opening with praise for the Supreme Leader’s environmental vision. The level of the science was low, Palmer said.

“Mostly they just talked about planting trees,” she said.

Hand tools, not tractors

The visiting scientists were segregated from the North Korean participants at every coffee break, and when Palmer—a river specialist consulting on soil issues—tried to offer the meeting’s organizer a thumb drive loaded with scientific literature, it was spirited away by security.

After the conference, the delegation was bused outside Pyongyang to visit the country’s Central Nursery, where special seed stocks were developed, and a wildlife preserve.

The nursery was the source of the seedlings for the national tree planting program, and Neureiter said their hosts showed them what were presented as advanced materials that would allow the little trees to travel long distances without drying out.

“You come away with an impression that this is really a good program,” he said. “You have no idea, however, how big it is, how many trees they’re really planting a year and so on.”

Palmer said the lack of equipment and the fact that the seedlings seemed to be cultivated by hand with primitive tools led her to doubt trees were being produced in the numbers their hosts suggested.

The rides outside Pyongyang proved more instructive, she said. With the exception of a few antique tractors from the mid-20th century, most of the work on North Korea’s farms seemed to be done manually.

“People were in the fields. A lot of them were women, but there were men, too—planting seeds and pulling plows,” Palmer said. “There’d be a woman in the front with a harness on and a woman in the back.”

The workers were thin, and many had brush or branches or leaves on their backs. She came to realize that propaganda had convinced them that a U.S. air strike was imminent and they were attempting to camouflage themselves.

Palmer declined an invitation to return to North Korea. But Neureiter made the trip five times between 2006 and 2017, even planting a tree during one visit and returning to see it on another trip.

He criticized Trump’s travel ban in 2017, enacted after the death of U.S. college student Otto Warmbier from injuries sustained in a North Korean prison. Neureiter argued that scientific exchanges have an important geopolitical purpose.

“We would be willing to do any acceptable joint project, because we think cooperation lays the basis for peace,” he said.

Neureiter was involved in two years of seismic testing at Paektu Mountain, a volcano near North Korea’s border with China that had shown signs of activity in the early 2000s. China and North Korea were both concerned, he said, but weren’t sharing information until international researchers became involved.

“There was a bit of a plan to go on with further studies,” he said. “And the Chinese also for the first time are communicating with the North Koreans. But everything is stopped right now. We’re just waiting to see if there’s some kind of [nuclear] agreement, and then we can continue.”

Reprinted from Climatewire with permission from E&E News. E&E provides daily coverage of essential energy and environmental news at www.eenews.net.