'What If This Were Your Kid?'

Young offenders in juvenile detention don’t get the best education. But those held in solitary confinement can go weeks, even months, without any instruction at all.

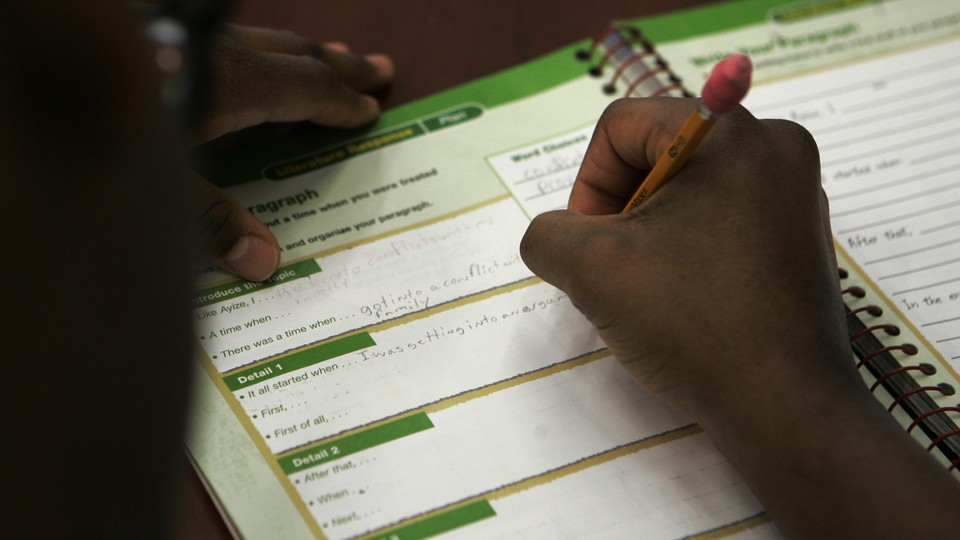

At the Onondaga County Justice Center in Syracuse, New York, between 2015 and 2016 more than 80 teenage offenders were regularly locked in solitary confinement. They’d spend 23 hours a day, seven days a week, in dimly lit cells measuring roughly half the size of an average parking space. In lieu of regular schooling, they were given photocopied pages of a high-school equivalency workbook, which they were left to complete, or not, without supervision or review. These circumstances are far from isolated: Across the country, young offenders in solitary confinement experience gaps in their education that can leave them unprepared to return to school upon release—if they return at all.

In Onondaga, “many of these kids had [individual education plans] in special education, and they were clearly not assessing where these kids were at,” said Louis Kraus, who is chief of the child and adolescent psychiatry department at Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Kraus conducted interviews with the young detainees in Onondaga and inspected their educational materials as part of a lawsuit filed by the New York Civil Liberties Union and Legal Services of Central New York. “So here you have kids that are already at risk for learning disabilities and other educational struggles, and you make it far worse by not only not giving them the interventions that they need, but not even providing basic educational attention,” he said.

According to the Justice Department’s Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, approximately 48,000 American kids were incarcerated in a private, state, or federal residential facility in 2015, the last year for which data is currently available. A number of states have already placed restrictions on solitary confinement for youth offenders. Beginning in January, for example, California will only allow it when other, less restrictive options have failed, and then only for four hours at a time.

Enforcement and oversight of these laws, however, vary widely, and so does the education young offenders are offered. It’s nearly impossible to attain an accurate tally of how many kids are in solitary at any given time, let alone how—and if—they’re taught. According to Jessica Feierman, the associate director of the Juvenile Law Center, some of the more extreme circumstances only come to light as the result of a lawsuit or intervention from the federal government. In 2014, for example, the Obama administration filed a “statement of interest” in a case against Contra Costa County Juvenile Hall in California, which alleged that “youthful offenders with disabilities who are confined [there] are often subjected to solitary confinement because of their disabilities and are denied special education, related services, and rehabilitation services.”

For many young offenders, education has long been a struggle. Peter Leone, a professor of behavior disorders at the University of Maryland who specializes in youth incarceration, said that kids who do poorly in school early on are more likely to be truant, or to participate in the sorts of low-level criminal activity that sends many kids to detention facilities. “That’s a really big issue, and it says volumes about the vulnerability of kids with special needs [within] a judicial system that is not very responsive or does not acknowledge the fact that poor kids, kids of color, kids with disabling conditions are much more likely to be detained,” he said. “And then once they’re detained, they’re more likely to be committed and kept in confinement for longer periods of time.” Leone was an expert witness for the plaintiffs in the Contra Costa case filed in 2013, as well as another in Los Angeles County in 2011.

“The question we always ask is, ‘What if this were your kid?’” said Mark Soler, the executive director of the Center for Children’s Law and Policy in Washington, D.C., which is campaigning to end solitary confinement for juvenile offenders nationwide. “After all, almost anyone in America could have their child arrested for possession of marijuana at some point, or shoplifting, or possessing alcohol underage. If we take those three, that probably covers most of the teenagers in America.”

While some kids are sent to solitary for committing violence, others are there for offenses that in a traditional school may not even warrant a teacher’s reprimand, let alone a trip to the principal’s office or a suspension, experts told me: being restless in class, talking back, or refusing to participate if they don’t understand or are frustrated by a lesson. And staffing shortages can influence how many kids are put in solitary: Detention-center workers responsible for a large group of teenagers often opt to simply send away so-called troublemakers—including those with learning disabilities or mental-health issues and those acting out. Depending on the facility and jurisdiction, kids can spend as long as 23 hours a day, seven days a week, for weeks or months on end in solitary. Sometimes, those detained don’t even know what offense they’ve committed, Leone said.

In some jurisdictions, young offenders in solitary receive no schoolwork at all, let alone dedicated instruction. “We had no schooling when I was in lockdown, maybe a book if a friend had one to share,” said Eddie Ellis, speaking at a Capitol Hill briefing on youth solitary confinement in August. Ellis was 16 years old when he was charged with manslaughter and served 15 years in prison. After his release in 2006, he became an advocate for young offenders reentering society. “So most of the time, you may write letters if they give you paper, maybe not,” he said. Ellis, who was diagnosed with dyslexia as a child, told lawmakers he was frequently sent to solitary confinement, with one stretch lasting four or five months after he argued with a guard who denied him a glass of water.

Outside of solitary, the education that facilities offer to young offenders can be substandard. Classes are usually grouped by age, not ability, and teachers attempt to find a middle ground, where everyone can follow along. Moreover, restrictions on items that can be brought into a detention center mean science classes are taught without beakers, Bunsen burners, microscopes, and anything that’s sharp or can be used as a weapon. Homework is rarely, if ever, assigned. A class-action lawsuit settled with public-interest groups in 2010 alleged the Lancaster juvenile facility in Los Angeles County “failed to provide constitutionally accurate education” to the kids detained there, including one teen who “graduated” without ever learning how to read.

“In juvenile facilities, classes are often bigger than those in public school, there is no teacher’s aide, and the teacher is aiming the curriculum at a sweet spot where all the students can understand what’s going on,” Soler explained. “But if a child is studying algebra and factoring binomial equations in high school in their public school, what do you think the chances are that when that child gets locked up, that the school in the facility is also working on factoring binomial equations? It’s very unlikely.”

As a result of their respective lawsuits, the Lancaster facility agreed to provide every kid in solitary a full day of schooling, which they attend with the general population; Contra Costa County agreed to end solitary confinement; and Onondaga eliminated solitary confinement except in the case of an immediate threat, and will provide access to special-education services.

Before they’re sentenced and sent to a state-run institution, many juvenile offenders are held at county-run facilities, where the educational program often isn’t accredited, and staff members, rather than teachers, oversee the classes. Much like a substitute teacher in a traditional school might play a movie rather than instruct the kids in an unfamiliar subject, these staff members focus on keeping the young offenders quiet rather than educating them.

“And the truth is, all those things happen in different places,” Soler said. “We’ve just seen so many institutional challenges to run a good educational program within a juvenile facility—it’s very, very hard to do.”

The Correctional Education Association, a trade organization for education professionals working within corrections, released sample standards in 2004, but like many educational guidelines, they are merely suggestive, and not widely adopted or enforced. Accountability for educating youth detainees often translates to a game of finger pointing; the local department of education blames the local bureau of prisons, and vice versa.

But Leone said government’s obligations are fairly straightforward. “As a rule of thumb, unless state law says otherwise, children who are locked up are entitled to the same level of services and support in education [as] kids who are not locked up,” he said. “Generally speaking, however, that’s just not the case.”

Many young offenders never make it back to school at all. A booklet issued by the Department of Education for students transitioning out of juvenile facilities notes that while 90 percent want to reenroll in traditional schools, only one-third actually do. A variety of factors can contribute to that gap: lost paperwork, a lack of parental or community guidance, trouble reintegrating into society, and trauma-related issues from detention and solitary confinement, among others. And even the most well-adjusted kid with all his or her paperwork, eager and ready to learn, might face an unwelcoming school district that refuses to take the student mid-semester.

“Kids will then stay out on the streets, commit new offenses, and get into trouble,” Leone said. “I really think those school districts need to be held responsible for the failure of these kids. They make it incredibly hard for those kids to get reintegrated. They make them feel like pariahs; they don’t welcome them back. And then we blame the kids for failing to meet the terms of the probation or parole when, in fact, the system has set them up for failure.”

This article is part of our project “The Presence of Justice,” which is supported by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge.