Secret Zuma Spacecraft Feared Lost – Facts, Speculation & In Between

The last heard of the enigmatic Zuma spacecraft was it was well on its way into orbit Sunday night, soaring away from Florida on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. Falcon 9’s first stage made an impressive rocket-powered U-turn to fly back to its Cape Canaveral landing pad while the second stage went on with its hush-hush task of dispatching Zuma to orbit out of public view.

Now, there are unconfirmed and conflicting reports Zuma may have been dead on arrival in orbit or has even re-entered the atmosphere after failing to separate from the Falcon 9 second stage.

Questions on Zuma’s health were raised on Monday after rumors started circulating that the spacecraft may have been lost. Ars Technica’s Eric Berger was first to publish a story on sources reporting Zuma may not have survived Sunday’s launch with one source claiming “the payload fell back to Earth along with the spent upper stage of the Falcon 9.” Stories published by the Wall Street Journal, Bloomberg and Reuters cite anonymous congressional sources confirming the mission is a loss but the articles offer unclear information and fail to grasp the difference between “failing to reach orbit” and various other failure scenarios that may have transpired.

Failures or potential failures on classified government missions, especially those with a high-profile for which Zuma is a leading example, always come with conflicting or unclear information, as well as intentional or unintentional leaks from within the involved government and industry parties. It is therefore of utmost importance to keep track of what is fact and where information is coming from.

For the recent developments regarding Zuma, facts are only precious few while second-hand information, unclear reporting and speculation are abundant.

The few facts for Zuma:

⚙ Zuma, or Mission 1390, was built by Northrop Grumman for an unspecified government agency, NG acted as launch vehicle procurement agent and has been on the SpaceX Manifest since 2015

⚙ The target orbit was Low Earth Orbit (ref. SpaceX Press Kit, November 2017)

⚙ Falcon 9 performed nominally during first stage flight (ref. SpaceX Webcast); long-exposure photographs of launch show what appears to be stable Stage 2 flight until at least T+7 minutes

⚙ SpaceX Statement: “We do not comment on missions of this nature; but as of right now reviews of the data indicate Falcon 9 performed nominally”

⚙ Northrop Grumman Statement: “This is a classified mission. We cannot comment on classified missions.”

⚙ The Joint Space Operations Center cataloged one object related to this launch as USA 280 (2018-001A), indicating the mission reached orbit and completed at least one full revolution

⚙ Photographs show the Falcon 9 second stage over Africa two hours and 18 minutes after launch

⚙ No NORAD catalog entry was made for the Falcon 9 second stage & the U.S. Strategic Command is on the record saying it has “nothing to add to the satellite catalog at this time”

What also appears clear, though is not officially confirmed information, is that Zuma experienced a malfunction – enough so that Washington lawmakers have been briefed on the matter, according to agreeing information published by various news outlets. Reports are also in agreement that Zuma was lost due to a separation failure and re-entered Earth’s atmosphere.

On Tuesday, SpaceX went on the record again through a statement by company President and COO Gwynne Shotwell who categorically stated Falcon 9 is not to blame for anything amiss with Zuma:

For clarity: after review of all data to date, Falcon 9 did everything correctly on Sunday night. If we or others find otherwise based on further review, we will report it immediately. Information published that is contrary to this statement is categorically false. Due to the classified nature of the payload, no further comment is possible.

Since the data reviewed so far indicates that no design, operational or other changes are needed, we do not anticipate any impact on the upcoming launch schedule. Falcon Heavy has been rolled out to launchpad LC-39A for a static fire later this week, to be followed shortly thereafter by its maiden flight. We are also preparing for an F9 launch for SES and the Luxembourg Government from SLC-40 in three weeks.

This statement strongly implies and would support press reports that a behind-the-scenes blame game has started between SpaceX and Northrop Grumman – another common sight in the immediate aftermath of a high-profile & very costly space flight failure with involvement of more than one contractor.

From the initial statement by SpaceX and Shotwell’s comment on Tuesday, it is clear that the company has not seen anything in telemetry data from the mission that would implicate Falcon 9.

This rules out a number of scenarios in which Zuma would receive damage on its way to orbit and end up a dead satellite, e.g. a G-shock during ascent, excessive vibration, inadvertent contact at payload fairing separation, sudden fairing depressurization (all these would be readily apparent in telemetry data from accelerometers, pressure transducers and bus voltage sensors).

Shotwell’s statement also holds true even if Zuma re-entered along with the Falcon 9 second stage as long as Falcon 9 provided a nominal boost to the target orbit, issued the separation command to the Northrop-built separation system and then completed the second stage deorbit maneuver as it was programmed to do.

The claim of a failure to separate the Zuma spacecraft from the Falcon 9 upper stage appears to be substantiated by the Joint Space Operations Center:

Per the typical procedure, JSpOC will assign a catalog entry for every space object that reaches a stable orbit and completes at least one revolution around Earth.

The expectation for the Zuma mission would be two catalog entries: one for Zuma under a USA designation of U.S. military spacecraft and one for the Falcon 9 second stage named Falcon 9 R/B. A catalog entry for the upper stage was expected because it was to complete one and a half orbits around Earth before being intentionally deorbited toward a targeted re-entry over the Indian Ocean.

Re-entry was to occur over an area identified in a Notice to Airmen and Mariners published before launch to be active between 30.5° & 54.5° South and 63.5° & 125.5° East from two hours to three hours and 37 minutes after launch (3:00-6:37 UTC).

The lack of a second catalog entry, while not fully conclusive, is a very strong indication that only one object was tracked in orbit – adding merit to a payload separation failure. Falcon 9 R/B catalog entries were made for last year’s classified NROL-76 launch and the semi-classified X-37B OTV-5 mission that both had long second stage coast phases after payload separation and deorbited the second stage after more than one rev.

An independent confirmation that Falcon 9 reached orbit, stayed in orbit for 2+ hours and completed its deorbit burn comes in the form of photos taken from Sudan and an aircraft flying over the African country at 3:15 to 3:20 UTC, showing a bright spiraling phenomenon around three times the diameter of the Moon from the aircraft’s perspective.

Seen at 515 over Sudan. Timeline matches up for Zuma. 🚀🛰🇸🇩 Looks very unnorminal pic.twitter.com/OCDGdyGAZP

— Sam Cornwell (@Samcornwell) January 8, 2018

What is seen in these images is the aftermath of the second stage’s deorbit maneuver: to drop out of orbit for safe disposal, Stage 2 maneuvers into a retrograde orientation and re-lights its MVac engine to slow down sufficiently to place the low point of the orbit well into the dense atmosphere; the stage then undergoes ‘passivation’ by venting leftover propellant and pressurization gas.

The spiraling motion indicates the second stage was spinning as it expelled gas – some launchers intentionally spin their stages up before re-entry to induce aerodynamic break-up of the structure early in the re-entry process for a more complete incineration of the rocket body. Whether Falcon 9 employs a similar procedure is unclear; if not intentional, the spiral pattern could be the result of a loss of attitude control during or after the deorbit burn.

From the available factual information, agreeing source reports and photographic evidence, it would be reasonable to conclude that a payload separation failure is the most probable explanation for Zuma’s fate (provided an orchestrated disinformation campaign can be ruled out). This would also explain the blame-game going on between Northrop Grumman and SpaceX since systems of both parties are involved in the separation of the spacecraft.

This is the image taken by Dutch pilot Peter Horstink, from his aircraft over Khartoum near 3:15 UT, 2h 15m after launch.

This is probably the Falcon 9 venting fuel.#Zuma pic.twitter.com/EEsl7e1sQP— Dr Marco Langbroek (@Marco_Langbroek) January 8, 2018

A November 2017 report by Wired cites a document confirmed by Northrop Grumman stating that the company is responsible for the Zuma spacecraft and its payload adapter connecting the satellite to the Falcon 9 Payload Attach Fitting (PAF) and forming the structural and electrical connection between the two. Payload adapters can be provided by the Launch Services Provider – typically the case for run-of-the-mill communications satellite launches or other standard satellites – or they can be custom-made by the spacecraft manufacturer for missions with special requirements.

To separate its payload, Falcon 9’s flight controls send the appropriate command which then goes through digital-to-analog conversion and arrives at the payload adapter as a specific voltage to set in motion the separation sequence (either through pyrotechnically triggered clamp-band systems or low-shock clamp-band systems / discrete point release mechanisms). The two fundamentals of the payload separation sequence are a) the separation signal arriving at the payload adapter in the correct form and b) the mechanical separation system working properly to release the payload.

In case of Zuma, step a) is a SpaceX responsibility and will have been verified by the company pre-launch through connectivity checks from the second stage control equipment all the way to the PAF as well as a simulated separation to verify the correct voltage arrives at the adapter interface. Step b), the actual separation action of the adapter, is typically simulated as part of satellite manufacture and testing (exemplary video of a separation test for an unrelated mission.)

However, testing steps a) and b) in combination with the actual flight hardware is not practical. It is therefore within the realm of possibility that an error in the PAF-to-adapter interface (where the SpaceX & NG systems come together) caused the separation command to not go through to the separation mechanism. In such a case, SpaceX would be able to verify through telemetry that the separation signal was sent correctly (i.e. “F9 doing what it is supposed to do”) while Northrop Grumman would cite confidence in their separation system obtained via rigorous testing.

SpaceX will have knowledge on whether separation actually occurred through break-wires that are used as a physical indicator for payload separation. Additionally, if Zuma remained attached, Stage 2 would have shown higher-than-predicted duty cycles on its reaction control system when performing attitude maneuvers with the additional mass of the payload and the deorbit burn would have needed a longer-than-planned burn duration to achieve its guidance-driven shutdown criteria (typically via a delta-v target).

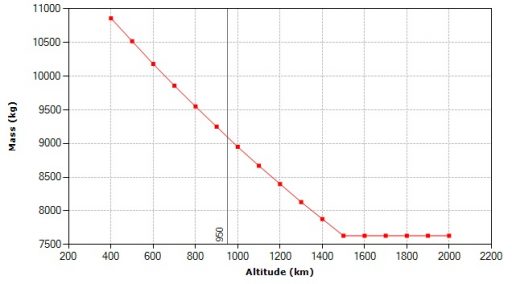

Propellant margins on the second stage were likely such that an extended deorbit burn could have been supported with ease:

The observations of the second stage over Sudan have provided a valuable data point for assessing Zuma’s target orbit which, before launch, had been estimated anywhere from 300 to 1,000 Kilometers, 50°. Taking into account the visual observation and constraints imposed by the Stage 2 impact area, a coarse calculation of the second stage’s orbit prior to the deorbit burn yields an orbital altitude between 900 and 1,000 Kilometers.

According to NASA’s Launch Services Program, Falcon 9 FT is capable of injecting 9,100 Kilograms into a circular orbit of 950 Kilometers (with RTLS landing as performed on Sunday). The largest publicly known satellite designs of Northrop Grumman, based on the Eagle-3 platform, would not exceed five metric tons – leaving more than enough fuel margin on the second stage after orbital injection to deorbit the combined stack.

Although sources seem to agree that Zuma re-entered along with Stage 2, one outside possibility that bears mentioning is the spiral pattern seen over Africa – if not intentional – could be a visual indication of the second stage spinning out of control around the time of its deorbit burn (possibly due to the off-nominal center of mass properties with the payload still attached). In this case, the deorbit burn might not have been successful and the Zuma-Stage 2 stack could still be in orbit.

Zuma has been an unusual case from the beginning – showing up on SpaceX’s public manifest with only a month’s notice before the target launch date and setting a new benchmark for secrecy in modern-day spaceflight. It was also clear before launch this mission was treated slightly differently than SpaceX’s previous launches – apparently up to the highest level as there are unconfirmed reports of SpaceX CEO Elon Musk informing his workforce to be vigilant of any inklings of issues since Zuma was the most valuable satellite they had ever handled.

While a successful launch would have been the conclusion of Zuma’s story – at least until declassification in several decades – the apparent failure of a mission worth north of a billion Dollars will likely mark the opening of a second act.