-

PDF

- Split View

-

Views

-

Cite

Cite

Holly Brewer, Slavery, Sovereignty, and “Inheritable Blood”: Reconsidering John Locke and the Origins of American Slavery, The American Historical Review, Volume 122, Issue 4, October 2017, Pages 1038–1078, https://doi.org/10.1093/ahr/122.4.1038

Close - Share Icon Share

Abstract

Historians of slavery in America—most notably Edmund Morgan—had their ideas shaped by the struggles of the Cold War, and debates over the connections between political and economic liberalism. As we have paid more attention to slavery, we have made increasingly strenuous efforts to rationalize slavery, democracy, and capitalism, efforts that have also occurred in other academic fields, ranging from philosophy to political theory to sociology and literature. Many of these efforts, for right or wrong, have focused on John Locke, a crucial figure of the Enlightenment and the beginnings of modern democratic ideals. In this article I contextualize Locke’s ideas and actions with regard to slavery in the empire to argue that we need to begin with different assumptions and questions. Those policies did not emerge from Locke, but instead from those he argued against: the Stuart kings. To understand the origins of slavery, we need to pay more attention to how various laws and policies enabled it across the empire, to who was behind those policies, to who profited the most from those policies via customs on imported staple crops, and to how those policies were initially rationalized. Slavery was created in legal pieces—pieces written, approved, and rationalized in hierarchical political contexts by Charles II and his brother James II. They had origins in older feudal law, with new innovations to make them more capitalist—but the larger rationale was in principles of absolutism and the divine rights of kings. There are powerful connections between monarchy, oligarchy, lordship, and slavery; all emphasize hereditary status. It took force to implement and get access and control enslaved labor and collect taxes; the power of empire was critical to each part of slavery’s development. When Locke had real power in the 1690s on the Board of Trade, he helped to reform Virginia laws and government, objecting especially to royal land grants that had rewarded those who bought “negro servants.”

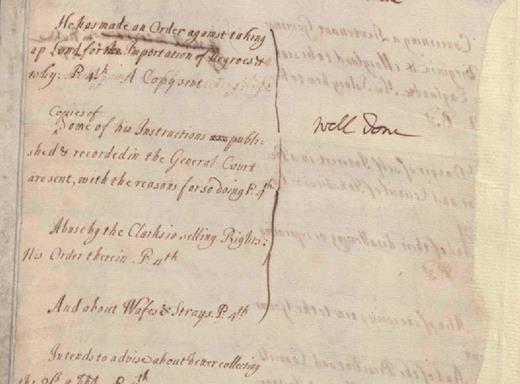

Responding to a 1699 report that Virginia governor Francis Nicholson had “made an order against taking up land for the importation of negroes,” John Locke wrote: “Well done.” The spindly marks of Locke’s quill—small marks among voluminous reports of imperial administration—were the culmination of his efforts to implement his forty-page plan for law reform in Virginia—a plan found rolled up in a cubbyhole in his desk when his papers were given to the Bodleian Library after World War II.1 When put in their broader context, they reveal Locke’s animosity toward slavery in many forms, an animosity he developed in reaction to royal support for absolutism and slavery. Imperial power structures were crucial for the development of slavery, and once established were difficult to dismantle.

Locke’s scratchings from three centuries ago remain relevant, not only because they illuminate his struggle to change a royal policy that promoted slavery, but also because they show how imperial power mattered to slavery’s development in the British Empire. Slavery was not a single iconic status; it was the product of many laws and policies. Locke’s actions are relevant because of his influence on the American revolutionaries, and in turn because those ideas have shaped how historians and political scientists define historiographical and philosophical debates about democracy, the Enlightenment, liberal capitalism, American and English exceptionalism, and slavery. Widely read in his own time, Locke was cited more than any other thinker in American newspapers of the revolutionary era, and he continues to be widely taught as the foundational thinker about democracy not only in American high schools and universities but also around the world.2

The relationship between Locke and slavery is not simply an abstraction of political philosophy, but rather a driving question behind rivers of philosophical and historical research. Arguments about Locke and slavery intensified during the Cold War, when scholars in many fields and in many countries debated the central tenets of political and economic liberalism, for which they viewed Locke’s philosophy as the foundation. The principles of Locke’s political liberalism, with their focus on rights and consent, appear contradictory to slavery. One work that continues to influence political philosophers as well as historians is C. B. Macpherson’s The Political Theory of Possessive Individualism (1962). Macpherson voiced the now-accepted interpretation that Locke supported slavery because he supported property above all else, even property in people. Edmund Morgan and other historians drew explicitly upon Macpherson’s interpretation of Locke when raising fundamental questions about the history of slavery and American democracy.3

Historians’ approaches are still influenced by the Cold War determination that America was attached to distinctive English freedoms from the beginning, if only for whites. England’s empire emerged within a liberal Lockean context with elected assemblies that made colonial law, including slave law. British America never partook of the “feudal” or absolutist principles that preceded Locke’s liberalism in Karl Marx’s theory of economic development.4 Slavery developed by popular consent of the white colonists within each colony, driven both by inherent racism and by capitalist desires to accumulate. Winthrop Jordan’s 1968 assessment that slavery was an “unthinking decision” based in deep racism and economic aspiration helped to undergird the interpretation of David Brion Davis: racism was so ingrained that one had rather to explain freedom than slavery for blacks. Over the past fifty years, most of the books on American slavery have focused on how laws and practices developed in each colony separately, as though they were in truth self-governed. Even studies that consider slavery more broadly within England’s empire describe how colonies developed their own “customs” of slavery, as though they all occurred without an imperial power structure.5

Even as American historians have expanded our view to encompass empire, and even as historians of other empires have situated the emergence of slavery within hierarchical ideas about lordship, historians have been stuck in a narrative that equality for whites came only at the expense of inequality for blacks. It has been a fruitful frame, in many ways, but also a limited one. It hides complexity and conflict and reinforces American exceptionalism. Such an argument was most clearly stated by Edmund Morgan in his paradigmatic American Slavery, American Freedom (1975). American freedom literally depended on American slavery: “This is not to say that a belief in republican equality had to rest on slavery, but only that in Virginia … it did.” By extension, America was always liberal and racist—a starting point that has profoundly shaped the debate about American slavery over the past half-century.6

The consensus draws, often implicitly, upon Marx’s theories of political and economic development, which maintain that political liberalism and capitalism emerged hand in hand, but only after feudalism disappeared. Whether explicit or not, it influences recent work by Abigail Swingen and William Pettigrew, who have expanded Morgan’s thesis to a seventeenth-century imperial context. They argue that liberalism (whether from Cromwell or the Whigs) led to freedoms for whites, including especially their ability to have “free trade” in slaves. Lorena Walsh and Wendy Warren likewise emphasize that slavery was capitalist—merchants, even in New England, traded people for profit, and planters cared about little else. Indeed, we historians are in the midst of a veritable flood of books, from scholars such as Walter Johnson and Sven Beckert, that emphasize that slavery was capitalism, and not the kindly feudal paternalism (also inspired by Marx) of Eugene Genovese’s later work. We now know the details about human beings whose body parts were marketed in American slave auctions and how much profit greedy slave owners made as they expanded plantations west during the nineteenth century. These books build on markers set down by Macpherson, Morgan, and others. Slavery was capitalist. Therefore, if capitalism and political liberalism are intertwined, slavery created modernity, both political and economic. Although in Marx’s theory slavery preceded both feudalism and capitalism—a nicety that is quietly ignored—our net verdict is that American slavery was part of a liberal-capitalist, modern order.7

Ira Berlin, Peter Wood, Philip Morgan, Christopher Tomlins, Simon Newman, and Anthony Parent are among those who have complicated Edmund Morgan’s narrative, pointing to stages in slavery’s development and the degree to which it was a “terrible transformation.” So too have historians of gender like Jennifer Morgan and Kathleen Brown, who see slavery developing in a more patriarchal environment, with women’s debasement a marker for larger inequalities.8

By situating the emergence of slavery within controversies over imperial principles and practices in the seventeenth century in which Locke was directly involved, it is possible to step outside the old paradigm and gain precision regarding the origin and political meaning not only of Locke’s ideas, but also of slavery. Slavery did not emerge within a liberal paradox. English kings of the Stuart dynasty—James I and his son Charles I and grandsons Charles II and James II and great-granddaughter Anne—justified their divine and hereditary status with the same principles they used to justify slavery. For the Stuarts, race was subsumed within a larger rationale celebrating hereditary status. One was born a slave, just as one was born a prince.9 Legally and ideologically, slavery was anchored in hierarchical and feudal principles that connected property in land to property in people, principles that were bent to new forms in England and its empire by Stuart kings. By the late 1670s, it was distinguished in the West Indies by a separate legal system that stripped people of their rights, and that had many components (such as slaves’ inability to testify against masters). Slavery was created in bits and pieces. Liberalism emerged in reaction to such principles—and not simply in the writings of Locke, though his writings provide a convenient window into that conflict. Liberalism emerged in opposition to slavery and absolutism.

Moreover, trade in people and political liberalism were and are fundamentally at odds. There is no such thing as “free trade” in forced labor—forced labor requires the power of the state, and its navies and armies and militias and slave patrols and county court judges. Political liberalism began by rejecting such force, except as punishment for a crime. Capitalism, however, takes many forms, and some are more compatible with political liberalism than others. It is not enough to see “slavery” and “capitalism” as unitary concepts; they should be viewed as multifaceted, shaped by debates over the fine points of laws of justice.

Locke could never have written Two Treatises of Government, and could never have challenged the Stuarts, had he not first cooperated with them. Cooperation gave him the knowledge and ability to protest effectively. Locke accepted the Restoration of Charles II in 1660 and worked for him between 1669 and 1674. But in 1674, Locke’s mentor the first Earl of Shaftesbury and a new Whig opposition challenged principles of monarchical absolutism and slavery. Within that movement, Locke developed a philosophical argument against both hereditary hierarchy and property in people. Whig resistance culminated in the Glorious Revolution against James II in 1688, a revolution that Locke justified in Two Treatises of Government (a book widely read then and still viewed as foundational to democratic theory). William III appointed Locke and his allies to oversee colonial policy to fulfill the promises of the Glorious Revolution.10 These men then tried to undo Stuart imperial policies pertaining to large estates, bound labor, and oligarchy. Such policies, they argued, subjected everyone to degrees of slavery. But shifting the course of empire required redirecting powerful currents.

Locke was born in 1632, and his childhood was shaped by a terrible contest over the basis of government: Do kings have absolute power by divine sanction, or should the people, via their representatives in Parliament, be consulted? During his youth, his father fought for Parliament in a civil war that killed one-tenth of England’s men. In January 1649, when Parliament tried Charles I for treason against his people and then executed him, Locke was attending school within sight and sound of that trial and execution. In 1653, he published odes to Cromwell’s victory over the Dutch.11

But in January 1660, Locke wrote to his father in despair over the anarchy in the former Commonwealth. The remnants of elected government in England were in ruins. Locke could not “thinke to enter upon a steady course of life whilest the whole nation is reeleing.” London mobs and rival parliamentary armies were readying to fight each other. “In this time when there is noe other security against mens passion and reveng but what strength and steell yeelds I have a long time thougt the safest condition to bee in armes could I be but resolvd … for whome to imploy them, or could be but securd that I should not spend my bloud to swell the tide of other mens fortune or make myself a c[ar]kas for their ambition.” He would fight, if only he knew for whom. “Tis the great misery of this shatterd and giddy nation that warrs have producd noething but warrs and the sword cut out worke for the sword.”12

Amidst such anarchy, two parliamentary leaders, Anthony Ashley Cooper—later Locke’s mentor, and most commonly known today by his later title, Shaftesbury—and George Monck, shifted their support to Charles Stuart. In a speech to Parliament, Shaftesbury’s conservatism is evident: he worried that even if England avoided anarchy, uneducated servants would rule the country. A return to the principles of lordship was his only solution.13 Therefore, he and Monck, who led the largest army, negotiated compromises with Charles at Breda to restore him as King Charles II, with great hope and celebration.

During the fifteen years following the Restoration, those who sympathized with Commonwealth principles witnessed a crackdown on the king's opponents and renewed enforcement of the king's divine right. With the new Cavalier Parliament’s support, Charles II abandoned the pardon he had promised at Breda and prosecuted everyone who had participated in his father’s trial.14 He oversaw the dismissal of two thousand ministers from the Church of England and approved laws to punish those who attended “dissenting” churches. The Book of Common Prayer added a new holy day (holiday) and religious service in 1662 to commemorate the Restoration. Every year on May 29—a holiday even in Virginia—the people were supposed to swear to obey Charles II and his heirs: God alone could judge the king. The people’s rote responses in church were called their “suffrages” or votes, whereby they swore an oath before God acknowledging the king’s divine right to rule over them: “humbly beseeching thee to accept this our unfeigned, though unworthy oblation of ourselves; vowing all holy obedience in thought, word, and work unto thy divine Majesty; and promising in thee, and for thee all loyal and dutiful allegiance to thine Anointed servant, and to his heirs after him.” The king, as head of the Church of England, ruled as God’s representative on earth. As God’s “Anointed servant,” he was “dread Sovereign Lord” over his people.15

Such ideas about the divine and hereditary power of kings and the duties of subjects emerged earlier, but foretold later justifications of slavery. As Charles II’s grandfather James I wrote in 1598: “The duty and alleageance, which the people sweareth to their prince, is not only bound to themselves, but likewise to their … lawfull heires and posterity, [to] the lineal succession of crowns … [N]o objection … may free the people from their oath-giving to their king, and his succession.” Kings inherit the right to rule; subjects inherit the obligation to obey: and so did slaves inherit the obligation to obey masters. Principles of hereditary obligation were propagated by politicians, preached in sermons, and recited in catechisms.16

Stuart plans for colonial development drew on such principles: in proprietary charters, Charles I granted some of his own “Regall Authority” and “absolute” power to lesser lords. In his grant of the Caribbean to the Earl of Carlisle, King Charles I wrote: “we do create and ordaine [him] absolute Lord.”17 Legal concepts of dominion or lordship justified both monarchy and proprietary power. Charles I and later Charles II granted proprietors not only the land but also the right to govern the inhabitants of colonies such as Barbados, Carolina, and New York. Despite notable exceptions in New England and Pennsylvania, in most cases Stuart kings chose men who shared such principles —whether as royal governors, appointed officials, or great proprietors.

In practice, the legal concept of dominion took the form of headrights, which encouraged lordship, large estates, and bound labor. Barbados’s first proprietor, the Earl of Carlisle, gave men ten acres of land for each servant they owned. By royal proclamation, Charles I and Charles II promised “headrights” of fifty acres of land in Virginia to anyone who bought a servant, whether white or black. Charles II instructed Governor Thomas Culpeper that “every person that shall transport or carry servants thither shall, for every servant soe carried and transported, have set out to him, upon the Landing and Imployment of such servant, Fifty acres of land, To have and to hold to him the said Master, his heirs and assigns for ever.” Between 1635 and 1699, Virginians claimed four million acres for importing 82,000 white and black “servants.” In August 1664, Charles II likewise agreed to “granting away the first million acres alloweing thirty acres per head to [to masters who import] men women and Children white or blacke, for the latter further the Plantation as much and Doe asmuch produce the goods that shall pay Custome and fill shipps.” Note here the claim that “blacke” laborers were even better than white at producing crops to be taxed in England. The king even permitted respectable Englishmen who “have good Estates, & doe ingage to bring on more people” to claim the headrights that would accord with their plans to import that many people. A prosperous man who planned to import “an hundred hands” could claim thirty acres for every person he planned to buy, and therefore the king would reward him with a contiguous estate of three thousand acres.18 Masters thus assembled large plantations with bound labor under royal aegis.19

By encouraging mass production of staple crops that were heavily taxed, royal headright policy dramatically increased crown revenue. Even in 1636, Virginia tobacco generated £42,000 in net crown revenue for Charles I. After 1660, Parliament granted Charles II higher taxes on tobacco and sugar imported into England, and rates increased again in 1685 at James II’s request. By 1687, gross crown receipts from tobacco taxes were £725,648 out of net crown income of just over £2,000,000. Tobacco customs paid the national debt and paid for James II’s custom collectors, navy, and standing army of 40,000 men.20

After the Restoration, principles of hereditary status, especially hereditary servitude, complemented crown revenue. Hereditary servitude thus became an organizing principle behind the king’s empire. Charles II’s first step was to establish the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading into Africa, later the Royal African Company (RAC), under the leadership of his brother James, Duke of York, and with most of the royal family as members. Promising his governors to supply the colonies with “conditional [English] servants and blacks,” Charles II coordinated colonial policy with the African trade by promoting RAC factors, or salesmen, to powerful colonial posts, such as Thomas Modyford to the governorship of Jamaica in 1664.21

One motive for Charles II’s marriage in 1662 to Catherine de Braganza, princess of Portugal, was her dowry, which included the legal right to Portugal’s castles on the African coast that the Dutch “illegally” occupied, according to a secret part of Charles II’s marriage treaty. Between 1661 and 1675, Charles and James allied with the Portuguese to fight Dutch control of over a dozen castles off the African coast. Once conquered, such castles provided a base of operations for the RAC trade in Africans. As admiral of the fleet as well as director of the Royal African Company, James, Duke of York—with an open license from his brother to attack where he wished—directed the war toward Africa. The new castles created alliances with African princes, who sold their enemies to the English as servants, prevented other European ships from landing, provided prisons for human cargo, and served as sites of exchange. James governed the company for twenty-eight years, during which time it sent more than 100,000 souls from Africa to the New World. After 1685, he was also king of England.22

Likewise, only with the restoration of hereditary monarchy in 1660 did colonies pass laws enshrining hereditary slavery: Barbados in 1661, Virginia in 1662, Jamaica and Maryland in 1664. These laws were a response to Charles II’s explicit requests to his governors in 1661 to support the RAC and to codify their laws. William Berkeley of Virginia, like other governors, had to obtain the approval of Charles II and his Council of Foreign Plantations for all laws.23

Before 1660, colonial laws treated “servants”—as both whites and blacks were usually called—similarly, if badly. English subjects became servants when they “indented” themselves to a ship captain to pay the costs of passage. Their indentures, or contracts, allowed them to be bought and sold. Others were kidnapped and sold without contracts, as were most Africans sold to English colonists by privateers who raided Portuguese and Spanish settlements. African servants, like English, had jury trials, could witness (if they could swear an oath), could be manumitted, and could own land and servants themselves when freed. But in some colonies, courts began to treat Africans as more permanent, and even hereditary, servants, with arguments that those who were not Christian and not subjects had fewer rights, with little legal certainty. Slavery was not an abstraction, but a gradual process of policymaking that stripped particular people of the rights of subjects and fostered a hierarchical social order.24 Only after the 1660s did elements of slavery emerge, and only after 1705 did full slavery emerge in Virginia, if one measures slavery by the legal structure that made it both a powerful and a viable institution.

Virginia’s post-1660 laws about bond slavery followed royal ideals that emphasized heredity.25 The 1662 law creating a holiday celebrating Charles II’s restoration “to the throne of his royall ancestors” was followed by the law making bond slavery hereditary: “All children borne in this country shalbe held bond or free only according to the condition of the mother.”26 Its language mimicked the thirteenth-century feudal law of Henri de Bracton: “He is born a bondsman who is procreated of an unmarried neif [female villein] though of a free father, for he follows the condition of his mother.” In mid-seventeenth-century England, royalists idealized Bracton’s “feudalism” as the source of ancient legal principles and reprinted his legal treatise.27 Though influenced by Spanish and Portuguese practices, which like Bracton had roots in Roman law, the Restoration’s celebration of divine and hereditary right shaped Virginia law.28

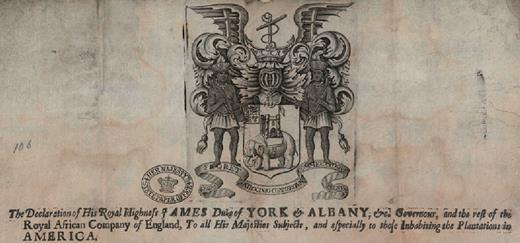

Charles II not only pledged his body and his sword to slavery; he pledged the coin of the realm. His new golden guinea displayed the elephant and castle, the symbols of the Royal African Company, under his own profile. Minted with gold from Guinea in Africa, such coins were the only way many subjects would see his face and connected the phrase “Dei Gratia,” “by the grace of God,” not only to his crown but to the slave trade.29 (See Figure 1.) Likewise, the seal of the Royal African Company read “By Royal Patronage Trade Flourishes.” It contained James’s ducal crest, a crown, and the admiralty anchor, supported by two Africans and the elephant and castle.30 (See Figure 2.)

Three coins connecting the king to the slave trade. Top: Charles II 1678 guinea (circulated and worn). First minted in 1663, the guinea got its name from the Guinea Coast, the slave-trading center of West Africa and the headquarters of the Royal African Company, which also exported gold. While few of Charles II’s subjects ever saw him in person, almost everyone saw his face on the coin of the realm. Because it bore the king’s own image, to forge or clip such a piece made a person guilty of the high crime of treason against the king. Note the inscription “Carolus II: Dei Gratia,” which means “Charles II by the Grace of God.” The inscription, the face, and the symbols linked the slave trade to Charles II’s own authority from God. Reproduced by permission of SarmatijaGBcoins. Bottom left: James II 1686 gold half-guinea (circulated and worn; smoothed from extensive handling). James remained governor of the Royal African Company even after he became king of England in 1685. Reproduced by permission of SarmatijaGBcoins. Bottom right: The elephant and castle of the slave trade also appeared on silver coins, such as this 1681 silver half-crown (worth 2 shillings sixpence, or 1/8 of a pound or about 1/10 of a guinea). A half-crown would have been in constant circulation, viewed by many. From Greg Reynolds, “Rare 1681 Silver Halfcrown of King Charles II, with Mark of the Royal African Company,” CoinWeek, September 3, 2014, http://www.coinweek.com/featured-news/the-1681-royal-african-company-halfcrown-of-king-charles-ii/. Reproduced by permission of Scott Purvis.

Top portion of a 1672 proclamation offering to supply colonists with “negroes” at set prices, from H.R.H. James, Duke of York, and the Royal African Company (which had a monopoly on the slave trade) “to all His Majesties subjects, and especially to those Inhabiting the Plantations in AMERICA.” The seal of the Royal African Company (in Latin) reads “By Royal Patronage Trade Flourishes, by Trade the Realm.” Note the prominence of the name of the king’s brother, later James II, as well as how his own ducal crest is incorporated into the center of the seal, along with the anchor of the navy (James was also admiral of the fleet). The National Archives, Kew, UK, Colonial State Papers, CO 1/29, no. 60. Reproduced by permission.

The Stuarts not only legitimated the formal enslavement of Africans, they supported what Shaftesbury and Locke called political slavery—by suppressing representative government and appointing local oligarchs to rule. In 1674, when James became governor of New York, he allowed no legislature. In Virginia, Charles II’s navy suppressed Bacon’s Rebellion against Governor Berkeley in 1677 with more than a thousand troops, enforcing imperial control at the point of a sword. Afterward, Charles II limited the authority of the elected burgesses in Virginia. He removed their judicial power, for example, making Virginia’s councilors, who held their seats at the discretion of the royal governor, the highest court as well as the most powerful legislative body, with the royal governor at the epicenter of power.31 In 1684, Charles II and James II suspended charters, abolished legislatures, and imposed royal governors and appointed councils in five northern colonies stretching from Massachusetts to New York when they created the Dominion of New England, an experiment in absolutist government.32 James II planned to turn the southern and Caribbean colonies into a parallel Southern Dominion under the control of a royal governor and appointed council.33

Scholarship on Locke and slavery has been shaped by two pieces of historical evidence that align him with the Stuarts: he drafted the plan of government for Carolina, the Fundamental Constitutions, in 1669, which supported both slavery and aristocracy; and he purchased stock in the Royal African Company in 1672. But Locke’s support for slavery was weaker than his critics have implied. First, he wrote Carolina’s constitution as a lawyer writes a will.34 He was paid to revise it and to make copies, and key principles of the document preceded his involvement. They were foreshadowed in the king’s charter and earlier proclamations from the proprietors that granted colonists, for example, headrights of fifty acres of land per “slave.” Locke drafted the final version of Carolina’s constitution for the eight proprietors who signed it. Six of the eight—all except Shaftesbury and Monck—had royalist principles, having fought for Charles I in England’s civil wars. As “the lords and proprietors of the province” of Carolina, they desired “that the government of this province may be made most agreeable to the monarchy under which we live.” They sought to “avoid erecting a numerous democracy.”35

While Locke continued to be involved with Carolina, the political chasm that emerged between Shaftesbury and the remaining proprietors undermined his influence. By 1682 Monck was dead, and Charles II had put Shaftesbury—whose one-eighth share of Carolina Locke was representing—on trial for treason.36

Likewise, Locke’s involvement in the RAC was of limited duration. He served as secretary to the Council of Trade and Foreign Plantations 1672–1674, a subcommittee of Charles II’s Privy Council with oversight over colonial affairs, over which Shaftesbury presided. In lieu of direct pay—Charles II was so broke in 1672 that he froze crown payments—both Locke and Shaftesbury were paid in Royal African Company stock.37 Both cooperated with Charles II in part to push for reforms in colonial governments such as Barbados.38 But in June 1675, Locke and Shaftesbury sold their shares.39

Locke and Shaftesbury broke with the Stuarts over their absolutist vision. In 1675, they co-authored a tract condemning Charles II’s increasing absolutism as the enslavement of all subjects, a tract that was burned as “seditious” by the common hangman. In July, Locke fled to France for his “health”; within the year, Shaftesbury was arrested and imprisoned in the Tower.40 Locke came back to England in 1679 during the Exclusion Crisis (when the Whig Parliament, led by Shaftesbury, tried to exclude James II from the throne), but he fled again to Holland with Shaftesbury in 1683, where he stayed, despite Charles II’s efforts to have him extradited on charges of sedition. In Holland, Locke and other English political refugees helped to plan the Glorious Revolution. His thinking about absolute monarchy and slavery culminated in his Two Treatises of Government, which challenged both. After its publication in 1689, it became the rationale for the Glorious Revolution.

The revolution was necessary, Locke wrote, because the principles of “an Advocate for Slavery” had become “the Currant Divinity of the Times.”41 By implication—even in 1689 he dared not name the former king—James II had advocated principles that enshrined hereditary hierarchy and absolute obedience for everyone. James II’s efforts to strip his subjects of rights grew from his absolutism, which made all subjects into slaves; such slavery was part of a continuum that ended in slavery in the Americas. Locke’s First Treatise opens with the words “Slavery is so vile and miserable an estate of man.”

Despite such words, most scholars, including C. B. Macpherson, argue that Locke supported real slavery in theory and practice. Orlando Patterson epitomizes the reigning interpretation: “Few writers have more bluntly stated this nearly universal way of rationalizing and symbolically expressing the condition of slavery than Locke: ‘having, by his own fault, forfeited his own Life, by some Act that deserves Death; he, to whom he has forfeited it, may (when he has him in his Power) delay to take it, and make use of him to his own Service, and he does him no injury by it.’”42

But the phrase “he does him no injury by it” meant that if a man started an unjust war, he committed a crime so great that his life was forfeit. Slavery could do “no injury” greater than death, because in lieu of execution, the criminal could agree to serve another as his slave in reparation for damage he had caused. In this “just war” theory, Locke followed natural law thinkers such as Hugo Grotius and English legal tradition back to Bracton in the thirteenth century.43 Slavery was justifiable only as punishment for such a crime.

For Locke, however, such slavery was temporary. The righteous conqueror who had repelled an unjust invasion could not take the invader’s property: that belonged to his family. The conqueror also had no right to the life or labor of the invader’s children: slavery, like subjectship, was not hereditary. “The absolute power of the conqueror reaches no farther than the persons of the men that were subdued by him, and dies with them: and should he govern them as slaves, subjected to his absolute arbitrary power, he has no such right of dominion over their children … He has no lawfull authority, whilst force, and not choice, compels them to submission.”44

Locke particularly opposed the Stuarts’ reliance on the common-law principle of dominion: that kings and lords inherited not only land but also “rule and power” over those who lived on it, and that the right of dominion was inheritable, transmitted from father to son, from time immemorial and forever. Not only was such a principle a myth, Locke contended, but it made a nation into slaves. Under James II, who claimed he owned all the land and thereby all the power to govern, “the Nation … was on the very brink of Slavery and Ruine.”45 Conquest does not create a nation of subjects who must slavishly obey their conqueror and his eldest son ad infinitum. Monarchs and their descendants do not have a right to rule on the basis of concessions granted by those they conquered under duress. Such coerced consent does not bind them, and most of all, it does not bind their descendants.

Locke disputed the claims of masters in the West Indies to rule over servants/slaves on the same grounds on which he critiqued James II’s right to rule: neither masters nor kings could claim perpetual and permanent hereditary power from Adam. It was a myth.

Claims to power over slaves in the West Indies were therefore as flimsy as the Stuarts’ claims of lordship or dominion, both based upon fraud. Neither monarchy nor lordship over servants was hereditary back to Adam. “Men and maid servants,” which he here also called “slaves,” were bought—not inherited. Such purchase could not legitimate the dominion of one man over another.Those who were rich in the Patriarchs Days, as in the West-Indies now, bought Men and Maid Servants, and by their increase as well as purchasing of new, came to have large and numerous Families, … can it be thought the Power they had over them was an Inheritance descended from Adam, when ’twas the Purchase of their Money? A Mans Riding in an expedition against an Enemy, his Horse bought in a Fair, would be as good a Proof that the owner enjoyed the Lordship which Adam by command had over the whole World by Right descending to him, … since the Title to the Power, the master had in both Cases, whether over Slaves or Horses, was only from his purchase; and the getting a Dominion over any thing by Bargain and Money, is a new way of proving one had it by Descent and Inheritance.46

Locke was challenging not only Caribbean masters' claims but also the high court in England that reified such mythology, legitimating their claims. Stuart court decisions in England and the colonies confirmed masters’ ownership of “negro servants”—invoking feudal law and its language of perpetual and hereditary status as well as introducing legal innovations that turned people into simple property. A 1677 high court of King's Bench case in which Charles II was indirectly involved, Butts v. Penny, cited feudal law to argue that “negroes” were hereditary villeins, forever owned and attached to the land, while also asserting for the first time that powerful legal mechanisms that protected the ownership of things could be used to protect the ownership of people. This passage from Locke directly challenges both the court's use of feudal law and the myth that people are things.47

Locke then challenged the intellectual link in feudal law between hereditary property ownership and hereditary power. Landownership granted no sovereignty: “How will it appear that propriety in land gives a man power over the life of another?”48 Even though land could be inherited, all children had an equal claim. Moreover, one’s title was secure only when there was “enough and as good left.” The main foundation for property derived from mixing one’s labor with the land: “As much Land as a Man Tills, Plants, Improves, Cultivates and can use the Product of, so much is his Property.” These arguments had profoundly destabilizing implications. They implied that great estates should be divided. While colonists might then use such arguments to justify taking Native Indian land in the Americas, such arguments could also justify the reverse if Indians were starving and colonial estates were uncultivated. Such arguments preceded Locke, and could justify the rights of squatters such as those who built houses in the king’s forests during the English Civil War. Locke’s concept of property denied the Stuarts’ principle of dominion over others.49 Instead, the most important principle of property was one’s ownership of one’s own life and liberty: “man” was “proprietor of his own person.”50

John Dunn and James Farr agree that Locke opposed slavery, but they condemn his inaction. Dunn described Locke’s failure to act against slavery as “immoral evasion.” Farr went further: on the question of slavery, he wrote, “Locke remained inert, frozen, speechless.”51 But he was not. After the Glorious Revolution that dethroned James II, Locke and others took steps to challenge Stuart slave policies.

At first, the new king and queen, William and Mary, focused on domestic stability and war with France. They retained many of James II’s imperial authorities, from Edmund Andros to William Blathwayt and Edward Randolph, although they shifted appointments, restored elected legislatures, and dismantled the Dominion of New England. William inherited James II’s former place as governor of the RAC, but he did nothing to support it, which meant that official trade with Africa disappeared virtually overnight.52 Although unofficial trade in Africans, outside the monopoly of the RAC, gradually increased, it did not match the levels of the 1680s. England’s ownership of RAC castles in Africa was in jeopardy.

Governor Andros and his council in Virginia tried to protect slavery in the face of William and Mary’s indifference. After the lower House of Burgesses crafted a bill about runaways, “for suppressing outlying slaves,” the unelected council, a legacy of James II’s reign, changed the law dramatically, adding clauses to strengthen the slave code. First, they prohibited manumission—which made slavery permanent. Second, they forced longer servitude on illegitimate “Mulattos.” While all bastards, orphans, and poor children (even whites) already faced servitude for twenty-one years, the amendment forced “Mulatto” children born to free white mothers to be apprenticed for thirty-one years. These amendments to deny manumission and extend servitude for “Mulattos” came from the appointed council—and were neither returned to the elected burgesses for approval nor sent to William III (sole monarch after Queen Mary’s death in 1694) for his. In 1692, Virginians established separate courts for heathens (read: slaves), which denied them trial by jury, copying earlier laws that Charles I had approved in Barbados.53

The two Virginia legislators who did the most to shape the slave code grew up in Restoration England and benefited from Stuart patronage. William Fitzhugh and Edmund Jenings moved to Virginia in 1673 and 1680, respectively, when each was just twenty-one years of age. Jenings arrived with a letter to Governor Culpeper from James, Duke of York, explaining that Jenings should be favored for “his father’s sake,” as his father, a Member of Parliament, had supported James during the Exclusion Crisis. Culpeper responded with alacrity, appointing Jenings attorney general of Virginia and clerk and sheriff for two counties surrounding the capital.54 Jenings and Fitzhugh gained estates by buying people and claiming headrights. In 1689 alone, Jenings received 6,500 acres for importing 131 servants, 23 of them “negroes.” By 1700, he had 20,000 acres and Fitzhugh 50,000.55 Both thereby accepted the principle that sovereignty over people equated to sovereignty over land.

Fitzhugh based his ideas for Virginia’s slave code partly on feudal law, as “out of the old fields must come the new corn.”56 “The reason must be sought for in old Authors … In Bracton, Britton, & Fleta … the blood of the father & of the mother are one inheritable blood, & both are necessary to the preservation of an heir.”57 Bracton sanctified not only primogeniture, which dictated who should inherit a kingdom and an estate, but also hereditary villenage with a parallel logic.58 When Fitzhugh wrote about “negroes” on his own estate, he emphasized their hereditary status: “& the negroes increase being all young, & a considerable parcel of breeders, will keep that Stock good for ever.”59

Fitzhugh retained such principles even in the face of revolution: he remained loyal to James II and his lineage even when confronted by mobs who shouted, “there being no King in England, there was no Government here.” In 1693 he toasted James II’s son as the next rightful king.60 After Marylanders reported Fitzhugh to the Privy Council for treason, the Virginia Council reluctantly put him on trial. Fitzhugh did not deny his loyalties; instead he implicated the councilors in his treason, insinuating “that Sr Edmd Andros himselfe ye Govr of Virginia, did Freely & openly talk of the same, amongst his Council, who also did the same without the least Notice taken.”61

William III turned his attention to the empire in 1696. Several factors shifted his and Parliament’s attention: the waning of war; the 1695 elections, which returned a radical Whig majority to the House of Commons; and the Jacobite assassination attempt against William in February. Although the Whig Party held only a slim majority in Parliament, their leaders (the so-called “Whig Junto”) pressured William to reform the empire, which was under his jurisdiction.62 Whig leaders, especially John Somers, threatened to shift governance of the colonies away from the king—and to themselves in Parliament—if he did not immediately institute reforms. The assassination attempt forced William to dismiss many Tories from the Privy Council, men who in turn had protected former colonial appointees. Likewise, after the attempted coup, he enforced loyalty oaths on all officials, even in the colonies, which led to shifts in colonial governance.

In this maelstrom of change, William created a new “Board of Trade,” which he packed with reforming Whigs. Its powers were similar to those of the former Council of Foreign Plantations, for which Locke had been secretary in the early 1670s: it reviewed colonial legislation, issued instructions to governors, approved appointments, and served as an appeals court, subject to the king’s final approval. William III chose its members with guidance from the Whig Junto led by John Somers. The board included Somers himself. Both William III and Somers begged Locke to assume a seat on the new board, probably due to Locke’s role in legitimating the Glorious Revolution and his former colonial experience.63 Three members were more conservative and had served as colonial agents under James II: William Trumbull, Charles Montague, and William Blathwayte, former surveyor of customs. But William III favored radical Englishmen he had known in Holland before the revolution. Three board members were former suspects in the Rye House Plot (a scheme to assassinate Charles II and his brother James in 1683) and Monmouth’s uprising against James II (Locke, Somers, and Ford Grey, Earl of Tankerville). The last member, John Methuen, was a commoner “of no position or wealth.”64

Despite the continuing conservative members, the new Board of Trade sought to limit the influence of Tory officials like Edmund Andros and to reverse many Stuart policies.65 With oversight over all colonies, they paid particular attention to Virginia. The first colony, and the largest, it had many problems. In October 1696, they interviewed Edward Randolph, William’s surveyor of customs, who reported that Virginia’s elite were in arrears on their quitrents and claimed large estates when other men had none. Such engrossment of lands made Virginia vulnerable. “Considering what vast quantities of servants and others have yearly been transported thither,” the colony of Virginia should be able to defend itself. However, “servants are not so willing to go there as formerly because the members of Council and others who make an interest in the Government have from time to time procured grants of very large tracts of land, so that for many years there has been no waste land.” Former servants “are forced to hire and pay rent for lands or to go to the utmost bounds of the Colony for land exposed to danger, and often the occasion of war with the Indians.”66

The board, led by Locke, then quizzed Randolph and others about headright policy, particularly about whether Virginia’s large estates had accrued from the importation of “negro servants.” Locke’s protégé and the clerk, William Popple, queried Randolph: “Are Negro Servants Understood to be Included or not, in the Number of persons that give a Right to any Portion of Lands, to those who Import them?” Randolph responded: “All Negro Servants, Men, Women, & Children give a Right to those who Import them, who thereupon, take up Land, contrary to the true Intentions of Seating that Country, but it being generally practised, to the advantage of some persons, No Notice is taken.”67 Locke continued the investigation by drafting “Queries to be put to Coll. Henry Hartwell or any other discreet person that knows the Constitution of Virginia,” which the board then used to interview Hartwell and James Blair (both members of the Virginia Council) and Edward Chilton.68

Locke was working so hard on such board business that he became seriously ill and was forced to leave London: “Business kept me in town longer than was convenient for my health: all the day from my rising was commonly spent in that, and when I came home at night my shortness of breath and panting for want of it made me ordinarily so uneasy, that I had no heart to do any thing.” In December 1697, he retreated to Oates, twenty miles away from London’s “stifling air.” Though relieved from “the constant oppression of my lungs,” he remained weak.69 During Locke’s illness, between January and May 1698, his secretary carried materials back and forth between London and Oates.70

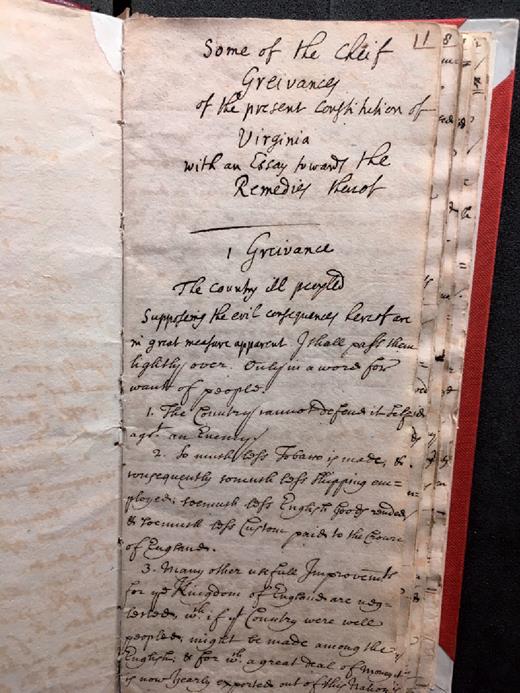

The evidence that Locke wrote “Some of the Cheif Greivances of the present Constitution of Virginia, With an Essay towards the Remedies thereof” at Oates is compelling. It begins in his hand and finishes in that of his personal secretary, Sylvanus Brounovwer.71 Drafts of the queries with notations in Locke’s hand, an evaluation of the various responses, and proposed corrections to Virginia’s laws and constitution were rolled up together for centuries in Locke’s desk. Bound together, they remain among Locke’s papers at the Bodleian Library.72 Not a formal committee report, the Virginia essay is written in the first person. Still, it is methodical, as Locke’s meditations often were. “The Conversion, and Instruction of Negroes and Indians is a work of Such importance and difficulty that it would require a Treatise of it Self. At present I should advise …”73 It covers the many issues raised with different informants over the board’s long investigation into Virginia. The “remedies” correspond to the principles of Locke’s Two Treatises of Government.

The first page of Locke’s forty-page plan for revising Virginia’s laws in 1698. “Some of the Cheif Greivances of the present Constitution of Virginia, With an Essay towards the Remedies thereof,” MS. Locke e. 9, fol. 1r, Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford. Reproduced by permission of the Keeper.

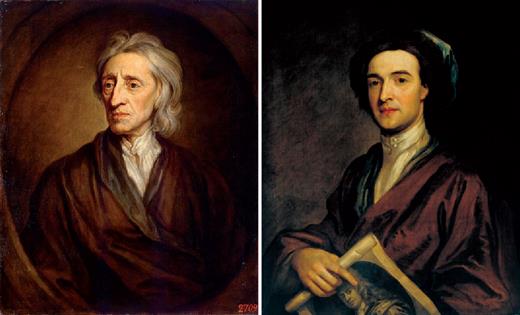

Though the sketch was in Locke’s desk when the Bodleian acquired his papers, and though the cataloguer attributed it to Locke, Peter Laslett, who helped to shape the modern Locke canon, later insisted that he could not have written it.74 Laslett was so inspired by Edmund Burke—whom he quoted frequently—on both Locke and the Glorious Revolution that it likely influenced his decision to exclude the Virginia plan.75 Laslett even portrayed Locke as an aristocrat, on a Board of Trade of noblemen, elaborately dressed and coifed—ignoring paintings of Locke in the 1690s, in which he is dressed simply, like a tradesman.76 (See Figure 4.)

Two portraits by Sir Godfrey Kneller: John Locke, 1697, oil on canvas. State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. John Smith the Engraver, 1696, oil on canvas. Tate Gallery, N00273.

Laslett’s decision to exclude the text from Locke’s corpus led later scholars of Locke to ignore it. When Michael Kammen published the Virginia plan in the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography in 1966, he followed Laslett in speculating that Virginia minister James Blair dictated the sketch to Locke: “They may very well have collaborated in Locke’s rooms in Mr. Pawling’s house in Little Lincoln’s Inn Fields [London], as Peter Laslett has picturesquely suggested.”77 In American Slavery, American Freedom, Edmund Morgan followed Laslett’s attribution, extending it to assume that Blair even composed the other Virginia papers in Locke’s handwriting (!). But the questions posed in successive drafts among Locke’s papers appear in their final form among the Board of Trade papers—alongside only answers from Hartwell, Blair, and Chilton.78 The location (at Oates), the handwriting, the marginalia, the power relations, the board’s long investigation into Virginia, the implementation of the sketch—all point to Locke’s authorship.

Blair credited Locke with the Virginia plan and the reforms it inspired. King William had appointed Blair to the Virginia Council as church representative after the revolution, from which post Governor Andros dismissed him in 1697.79 When Blair testified before the board in October 1697, he argued that Andros had stolen ministers’ salaries and the college’s building funds, complaints he repeated to the archbishop in December.80 But he never addressed headrights or the larger political and social questions in Virginia.81 Indeed, he wrote to Locke at Oates in January 1698 to beg him to get well enough to resume work on Virginia reform: “I can not but flatter my self with the hopes, that God, who made you such an eminent instrument of detecting the Constitution and Government of Virginia, will likewise furnish you with health and opportunities to redress the Errours and abuses of it.” Blair knew that Locke was fashioning a complex plan that required delicate negotiation: “I have not offered, since you went [from London], to stirre in any business at the Councill of Trade and plantations; fearing lest in your absence I should have marred and mismenaged it, by an untimely forcing it into other hands, and other methods than you had contrived.”82

From Oates in late May, Locke sent a letter suggesting that Francis Nicholson become Virginia’s new governor alongside the Virginia plan itself. Nicholson thanked Locke for “recommend[ing] me [as governor] to some of his most sacred majestys great ministers of state” on May 26.83 Five days later, in the first evidence we have about the Board of Trade discussing the Virginia plan, Blathwayt wrote to his fellow board member George Stepney that they were “now falling on the report about Virginia.”84

The Virginia plan began by condemning the existing headright system, which granted huge estates to masters for importing servants (both white and black), as “strangly perverted,” using arguments similar to those Locke expressed in Two Treatises of Government.

He used the same logic from his Two Treatises, that uncultivated land could be claimed by those who would farm it, to justify confiscating the uncultivated lands of Virginia’s elite.86 Such estates, he argued, could be confiscated legally via cultivation rules, escheats, and enforcing nonpayment of quitrents. Once confiscated, land should be redistributed in fifty-acre parcels to new migrants.87The ancient Encouragement of 50 Acres of Land per poll [person] … has been strangly perverted, and frustrated.

1. by granting the 50 Acres of every Servant to his Master that buys him …

By this trick the great men of the Country have 20, 25, or 30 thousand Acres of Land in their hands, and there is hardly any left for the poor People to take upp, except they will goe beyond the inhabitants much higher up than the Rivers are navigable, and out of the way of all business.85

Locke challenged not only their 20,000-acre estates, but also the omnipotence of Virginia’s “great men,” who held power under the same principles he had witnessed firsthand in England under Charles II and James II—the power that accorded with the principles of “an Advocate for Slavery,” as he wrote in the preface to Two Treatises of Government. A few men ruled Virginia as an unprincipled oligarchy. Such men must not hold multiple political appointments like councilor, militia captain, county court justice, custom collector, and member of the colony's highest court, the General Court. “It is a great Grievance that [the court] is in the hands of the Governour, and Council; Men utterly ignorant of the Law, impatient of contradiction, apt to threaten Lawyers and parties with imprisonment, if they use freedom of Speech, men that cannot be called to account for acts of injustice, Men that take noe Oath to doe Justice, Men that have made an order that they themselves shall not be arrested.” They are “Men that are under strong temptations to a byass [bias] in giveing their opinion by reason of the places of proffit they hold dureing the Governours pleasure.”88 This image of completely corrupt justice, with judges and councilors unaccountable and ignorant of the law, dismissed only at the whim of an irresponsible and power-hungry governor, is chilling. To rein in the council, Locke also recommended a more powerful legislature with annual elections (a huge reform), and giving that legislature a way to communicate directly with the Board of Trade. Ironically, as an employee of the king, Locke had to work through the king and the royal governor and that corrupt council to encourage reform. He also had to navigate between other powerful men—on the Privy Council and in the House of Lords, and the House of Commons—who had influence over colonial policy.

Within two months, Locke and his allies had translated the sketch into “instructions” for Virginia’s new governor, Francis Nicholson, to reform Virginia, especially its land policy. Five board members (four of them Whigs) signed the instructions: Locke, John Egerton (the third Earl of Bridgewater), Sir Philip Meadows, Abraham Hill, and John Pollexfen. Egerton, a prominent Whig, was leader of the House of Lords. Meadows had been Cromwell’s secretary and ambassador to Sweden and Denmark. Hill, treasurer to the Royal Society, collected scientific and social information from many colonies. Pollexfen, who had been on Charles II and James II’s Councils of Trade and Plantations, was both the only Tory and the only supporter of the African trade to sign the initial instructions. He later wrote: “The Trade to Africa deserves all incouragement … it carries from us, great quantities of our Draperies, made of our Coursest Wooll … in return we have chiefly Gold, and Elephants Teeth brought here, and great quantities of Negroes.”89

Other Tory board members disapproved of the effort to reform Virginia and never signed the instructions. Blathwayte was so opposed to the Virginia plan that he wrote angrily to Stepney: “I should think it a sin while I take the King’s money to agree to it.” Stepney worried: “tho’ abuses are certainly to be reformed, it is not decent in a Commission to censure preemptorily.” He concluded: “I am for moderation in all things, for violent changes are dangerous and difficult, and the attempt against all the officers of a plantation will certainly draw odium upon us.”90

Before the new instructions could become legal, the Lords Justices, who ruled during the king’s absence in Holland, needed to sign them. To gain their approval, Locke and his allies explained why they were seeking the reforms, highlighting headright policy: “we have added a new Method for taking up Land … the governour may also give an account to his majesty, in what manner the said Method may be introduced into practice.”91 The Lords Justices (John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough; Charles Sackville, sixth Earl of Dorset; Thomas Tenison, Archbishop of Canterbury; and Charles Montague, Chancellor of the Exchequer) accepted the new instructions, but not without alteration. They added a clause to support the African trade, particularly the new law that abolished the Royal African Company’s monopoly in exchange for a tax on goods from Africa, all except “negroes” and gold. That tax was meant to cover the RAC’s expenses to fortify and defend England’s “castles” on the African coast against other European powers. That law, which sparked the first of what would be eight such debates in Parliament over the next fifteen years, was not supported by Locke or his allies.92

The struggle over the governor’s instructions with regard to land and the African trade exposes the political minefields Locke was navigating. Sometimes he despaired: “The corruption of the age gives me so ill a prospect of any success in designs of this kind.” When a friend congratulated him on his appointment to the board, he responded:

Despite the political whirlpool and his health, Locke did try. In February 1699, Blair wrote Locke to thank him for reforming Virginia’s government.Your congratulation I take as you meant, kindly and seriously, and, it may be, it is what another would rejoice in; but ’tis a preferment I shall get nothing by, and I know not whether my country will, though that I shall aim at with all my endeavours. Riches may be instrumental to so many good purposes, that it is, I think, vanity rather than religion or philosophy to pretend to contemn them. But yet they may be purchased too dear … I think the little I have enough, and do not desire to live higher or die richer than I am. And therefore you have reason rather to pity the folly, than congratulate the fortune, that engages me in the whirlpool.93

Locke responded with modesty: “if I have been any way instrumentall in procureing any good to the country you are in, I am as much pleased with it as you can be.”95The tranquillity we begin to enjoy in this Countrey by the happy change of our Governour, and Government is so great that I who have the happines to know by whose means these blessings were procured have all the reason in the world to take all occasions of expressing my gratitude for them, and to pray to God to reward those noble publick souls that bestow so many of their thoughts, in contriving the relief of the oppressed, and the happines of mankind … this whole Countrey in generall and my self in particular are beholding to yow for the thoughts you was pleased to bestow on our late unhappy circumstances, and the methods you contrived to relieve us.94

As Nicholson reported his progress from Virginia, Locke read and responded. The difficulty of imperial change emerges starkly from their correspondence. Distances, obstructions from officials in Virginia, institutional rules and precedents, and factions on the board and Privy Council made reform slow and painful. To be able to tell this history has required analyzing thousands of documents buried in elaborately archived folders. In one letter alone, Nicholson enclosed more than seventy-five documents.96

In one such document, Governor Nicholson explained how he reversed the headright policy for importing “negroes.” As chief justice of Virginia’s General Court, a seat he held as governor, Nicholson denied the claim of William Miller for 220 acres, despite his “produceing a certificate of the Importation of Severall Negroes as Rights for the said Land.” Importing “negroes” no longer entitled men to fifty-acre headrights. “The said Rights are not good & Legall to qualifie the petitioner to take upp the said Land. And Ordered that it be an establish’d rule of this court not to admit of any Rights for Land [for negroes] but only for the importation of his Majesties Christian subjects into this Colony and dominion.” The court ordered that from then on, the headrights should go only to freed “Christian servants” themselves, not their masters.97

Nicholson’s verdict stated that he was following his formal instructions from Locke and the Board of Trade: “His instructions did not permit such Rights to pass.” The headright decision was signed by only Nicholson and three councilors: William Byrd, Edward Hill, and Jenings. The absence of the other nine councilors suggests that the verdict was unpopular. That Nicholson changed royal headright policy via Virginia’s (corrupt) General Court is ironic. Locke’s Virginia plan had criticized that power upon which he now relied: “by his great power, [the governor] can easily run down the barr, and sway the bench, and direct the Judgment what way he pleases.”98

Nicholson’s copy of the precedent-setting case was summarized by a clerk. Next to the clerk’s summary, Locke wrote: “Well done.”99 (See Figure 4.) Locke thereby applauded the reform of the “strangly perverted” headright system that had encouraged the importation of “negro servants.”

Locke always used the term “servant” or “negro servant,” never “slave,” in Board of Trade correspondence in the 1690s, which reflected his understanding of English law.100 As his comment on slavery in the West Indies in Two Treatises of Government indicates, he knew that it was becoming perpetual and hereditary there by 1688, a practice promoted by England's high court in Butts v. Penny in 1677. However, as the board began its investigation into Virginia in 1696, the high court of King's Bench overturned the earlier precedent in a shocking decision. That decision in Chamberlain v. Harvey invalidated the idea that people could be simple property. After freeing an enslaved man from Barbados, the King’s Bench declared that no man could own another. It technically turned “slavery” into temporary servitude across the empire, since colonial law could not be “repugnant” to English common law.101

Locke’s response to a report that the governor of Virginia, Francis Nicholson, had permanently reversed the fifty-acre reward of land for importing slaves. “He has made an order against taking up land for the importation of negroes,” Locke wrote in the margin: “Well done.” It was not, in fact, permanent, but it took a legislative act in Virginia, signed at every level including by Queen Anne, to reinstate it. The National Archives, Kew, UK, Colonial State Papers, in report to Board of Trade that summarized Nicholson’s progress in implementing the changes the Board had recommended in his official instructions, CO 5/1310, 8 (old pagination). Reproduced by permission.

As the English common law was turning against slavery in 1696, elite Virginians were hiding and pretending to repeal key elements of their emerging slave code. While the definition of slavery in the common law and in Barbados had rested not only on hereditary villenage but on a separate legal system for non-Christians, those elements were less developed in Virginia law. The board did most of its investigations without a copy of the colony’s laws—to their great disgust. Andros finally sent a handwritten volume of Virginia laws in June 1698, after Locke finished the Virginia plan and the new Governor’s Instructions, and some of the laws that we now know helped to create slavery are missing. Most importantly, the crucial 1662 law that made “bond” status hereditary was marked “repealed September, 1696.” However, the law was not, in fact, fully repealed, as a careful reading of hundreds of pages reveals; rather, it was folded into the final sentence of a long law “for Punishment of Fornication.”102 Only two laws mention slaves: one on runaways from 1691, “An Act for Suppressing Outlying Slaves,” and another from 1667 stating that “the baptism of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage.” Those pages are well-thumbed and slightly dirtier. One can imagine Locke’s inky hands paging through the volume that August.103

Repealing any of these Virginia laws was tricky. Locke could not suggest that the new governor ignore existing Virginia statutes, as that would undermine elected government. James II’s “dispensing” with English law had created the political crises that led to the Glorious Revolution. The declaration by the governor under James II, Lord Effingham, that he too was above the law and could ignore Virginia statutes was equally heinous: Governor Nicholson could not do the same.104

Still, Locke’s Virginia plan undercut the idea of separate legal systems: he encouraged Nicholson, as the plan wrote, to give people of all nations “equal privileges” as subjects under the law. “As people of different perswasions enjoy Lybertie of Conscience, so let people of all Nations be naturalized, and enjoy equal priviledges, with the other English inhabitants residing there.”105 Locke further suggested that the children of blacks should be “baptized—catechized, and bred Christians.”106 By encouraging baptism, he was undercutting the main justification for slavery common in England and throughout Europe. Once baptized, the former heathens could become potential subjects with rights, especially if bond status was no longer hereditary given the apparent repeal of Virginia's 1662 law that gave every child the status of its mother.107

The extent of Locke’s objection to property in people is evident in his objections even to indentured servitude: he supported bound labor only for criminals sentenced to hang. His question “whither several Delinquents had not better be sent to the Plantations (tho’ condemned to several years Servitude) than to be sent to Tyburne” to hang echoed his argument in Two Treatises of Government that slavery was better than death as punishment for a crime. Instead of servants indenting themselves to servitude to pay their passage, Locke urged the king to pay. Skilled tradesmen, the poor, “Native Irish,” and “French Protestants” should arrive without debt and receive land. He encouraged the king to diversify production on smaller farms—from crops like cotton, medicinal plants, raisins, and Indian corn to finished goods like silk, iron, and potash.108

While Locke made practical concessions—to merchants and Lords Justices and William III—his plan shows a commitment to government based on the consent of the governed and equality before the law. He challenged headrights for masters and bound labor.109 Such imperial reforms suggest that the Glorious Revolution was not Burke’s revolution. It was more radical, even if incomplete.110

Nicholson wrote the board shortly after Locke’s resignation in April 1700 to complain that few Africans were sent to Virginia: “I do not hear of any more Negroes being sent in, which I am sorry for, being they would make so much more Tobaccos, which I hope would increase his Majestie’s Revenue. Therefore I wish that the African Company and others that trade thither would send in some.”111 Nicholson’s letter suggests that the important and seemingly comprehensive list of slaves imported into the New World—the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database at www.slavevoyages.org—overestimates slave imports during this period. Pettigrew follows the database to argue that slave imports increased dramatically after 1698. However, the database for this period is unreliable. It interpolates from taxes levied on other goods imported to England and its colonies from Africa to make crude approximations of slave imports. Because such taxes were explicitly not levied on “negroes,” we simply have no concrete numbers for the slave trade during that decade.112

The real change in slave policy began only after William’s death from a hunting accident in March 1703. Queen Anne, who allied with high Tories, shifted policies on slavery both internally and externally, fighting to gain for England a larger share in the international slave trade. In 1697, for example, William Byrd (then Virginia’s agent in London) had begged William III’s Privy Council to acquire the Assiento, which would bring with it the right to supply the Spanish Empire with slaves. Doing so would mean a “Cheap and plentifull supply of [African] Servants.”113 While William did nothing, Queen Anne fought to gain the Assiento from France during negotiations over the Treaty of Utrecht in 1712.114 Robert Harley, Anne’s longtime secretary of state, played a crucial role in guiding the treaty through a reluctant Parliament. For such service, Queen Anne ennobled him and then made him director of the South Sea Company, to which she granted a monopoly on the Assiento. As a consequence of the treaty and Charles II’s earlier acquisition of the forts on the African coast, England transported more than half of the slaves sent to all of the New World by mid-century.

Queen Anne supported slavery across the empire. The old board under William III, for example, had repeatedly vetoed Virginia laws to restore headrights for importing slaves as well as the attempts led by the Virginia Council to pass a legal code for slaves. Edmund Jenings, who was in England on the council’s behalf to lobby the Board of Trade for such Virginia laws in 1703, understood the new political climate. Via dozens of letters to Queen Anne’s Board of Trade complaining about Nicholson’s “corruption,” Virginians first shed themselves of the governor. After Jenings became acting governor, he and the council pushed to regain headrights for masters who imported slaves.115 Jenings and the Virginia Council then rewrote and resubmitted headright laws that gave land to masters for “negroes” and other servants, laws that William’s board had formerly vetoed.116

In 1706, Queen Anne’s board approved a Virginia law giving bulk-bonus headrights of two hundred acres per servant/slave to masters who purchased more than five (ten new slaves earned their owner two thousand additional acres!).117 The board also ratified other Virginia slave laws that had been vetoed by William’s board, including one that barred heathens (meaning Africans and Indians) from testifying against Christians. They signed a new Virginia law compensating masters for the value of slaves executed for crimes, enabling a harsher system of punishment.118 This policy would become a crucial element of later American slavery, as it made masters more willing to see their slaves executed, and was one crucial element of a separate legal system for slaves. Perhaps most telling, the board approved another law allowing plantation owners to create permanent estates over generations, with slaves and their descendants attached to these estates like villeins. Slaves and their progeny could belong (with the land) to the lord and his heir ad infinitum, following feudal law of perpetual inheritance.119

By early 1706, then, elite Virginians and their new queen agreed on many incentives and protections for slavery. Between 1700 and 1755, the proportion of Virginians enslaved in the Tidewater leapt from less than 10 percent to a high of 66 percent, with lower proportions enslaved in the Piedmont and backcountry. These decades encompassed the “terrible transformation” from indentured servitude to African slavery in other colonies from Jamaica to South Carolina.120

The wealthiest Virginians not only favored hereditary status and slavery but opposed laws to protect liberties such as habeas corpus passed by the burgesses. Slavery and racism were part of larger arguments about hereditary status and lineage. Slavery was part of a broader denial of power to many, not just to African Americans. American slavery developed as part of broader debates about justice.

The contest over Locke’s plan shows that slavery was embedded in larger struggles over power and empire, and also that “slavery” was not one reified entity but was created and promoted with many policies and laws, all part of larger frameworks of justice. After 1675, radical Whigs such as Locke began to challenge hereditary status and forced labor. After 1703, Tories and more conservative Whigs sought to expand slavery by returning to Stuart policies and principles that drew on feudal law and mythmaking about perpetual and hereditary status. At the same time, they began to add extra elements that made the legal status of slaves ever more distinct in graduated steps.

Locke’s early involvement with the Stuart slave program gave him the incentive and knowledge to challenge it. While translating principles into laws is a messy business, full of compromise, as an old man he helped undo some of the wrongs he had helped to create. Radical in some ways but restrained in others, he argued for property ownership, but not in humans. He advocated redistribution of land to smallholders. He encouraged baptism of the children of Africans and Indians to make them subjects with rights, yet at the cost of their own religious beliefs. He opposed hereditary status. Finally, he objected to rewards for importing slaves and indentured servants.

Some reforms were later reversed, and others incompletely implemented, but we should not judge the revolution by the reaction. The Glorious Revolution shifted policy against slavery and toward representative government.121 It left a legacy in the reforms Virginia kept, including a college and a strengthened assembly. Arguably, that college—where Locke’s ideas were taught to later generations—provided a seedbed for America’s later revolution. But when Locke’s arguments against sovereignty and slavery reemerged, slavery was so deeply established that they were even harder to implement.

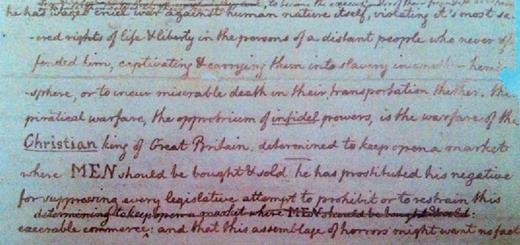

Not only kings but imperial policy had protected slavery and the slave trade for more than a hundred years. (See Figure 6.)he has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life & liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating & carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere … this piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian king of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where MEN should be bought & sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or to restrain this execrable commerce.123

The so-called “deleted clause,” removed from Thomas Jefferson’s original draft of the Declaration of Independence during debate at the insistence of the delegates from South Carolina. Philadelphia, July 1, 1776. Library of Congress.

In sum, debates about stages of economic development have obscured the complex history of slavery in ways that affect our ability to assess and regulate capitalism and corruption in the present. Political liberalism and capitalism are not complementary when capitalism allows property in humans; like slavery, capitalism assumes many forms. Theories of economic development that see feudalism and capitalism as opposites are misleading; in the case of American slavery, they developed together, with terrible consequences: Stuart kings manipulated feudal laws and principles to promote not only hereditary property in people but also trade in them. Slavery was part of a highly regulated and taxed market, one guided by the heavy hand of the royal state. Royal edicts like the headright to masters were rooted in feudal principles of dominion that promoted hereditary status. Virginia’s “feudal” laws such as entails on land and slaves hindered the free flow of capital, but also created economies of scale that made production efficient. Feudal variants interwove with capitalism to create an aristocratic system of large landowners and slaves, one entrenched by the American Revolution. It was this system of slavery that Locke and his allies challenged; in that challenge, the principles we now associate with democracy were born.124

Slavery in England’s empire emerged from laws and court decisions that drew on the principles of the divine right of kings; its opponents challenged both as inherently connected. Such debates burned fiercely during England’s Glorious Revolution, and again during the American Revolution and the Civil War. In 1858, Lincoln recognized the same origin of slavery traced here when he spoke of the “eternal struggle” between “two principles”:

The one is the common right of humanity, and the other the divine right of kings. It is the same principle in whatever shape it develops itself. It is the same spirit that says, “You work and toil and earn bread, and I’ll eat it.” No matter in what shape it comes, whether from the mouth of a king who seeks to bestride the people of his own nation and live by the fruit of their labor, or from one race of men as an apology for enslaving another race, it is the same tyrannical principle.125