Can you guess why the U.S. Navy pulled the above tweet less than 24 hours after posting? No, it’s not because of the emojis. Look closer. Can you see the battle scene in the far-left panel? You can almost make out the presence of a red flag with a crescent and star that resembles the Turkish flag. While it may not have been widely noticed in most of the U.S., the tweet sparked international outrage on Twitter from Turks, many of whom saw it as an act of American aggression.

I didn’t know about this tweet’s brief existence or its deletion until I filed a Freedom of Information Act request with the U.S. Navy. How could I have? When Donald Trump or a member of Congress deletes a tweet, we know about it thanks to projects like Politiwoops, which systematically keep track of these developments. But there is no Politwoops equivalent for Twitter feeds run by U.S. government agencies. So when agencies like the Defense Intelligence Agency, the Badlands National Park (remember that account’s brief infamy?), and others delete tweets, many of us never know about it.

Let’s be clear: These trends didn’t start with the Trump administration. The Navy tweet was nixed during the Obama administration. And that wasn’t the only Obama-era deleted tweet with some geopolitical significance. Back on July 16, 2016, a controversial tweet about Melania Trump posted by the Department of Justice Twitter account was swiftly deleted. On Sept. 3, 2016, someone at the Defense Intelligence Agency tweeted out a message that was critical of China; hours later, the tweet was replaced with an apology. More recently, the Pentagon retweeted and swiftly deleted a post calling on Trump to resign. When these stories happen, it usually emerges that a staffer used the official account instead of a personal one. Even accidental tweets can tell us something, though, and it’s hard to track the history of deleted tweets—in large part because journalists cover them as single embarrassing episodes.

As more and more records become born digital, the U.S. government has to think about the ethical ramifications of not just deleted emails but also deleted tweets, Facebook messages, Instagram posts. Without a consistent policy, we risk having an imbalance in the historical record, with some government agencies documenting and preserving everything and others erasing, eliminating, and expunging their actions. We need to document these deletions to better track how federal agencies choose to portray themselves—and how they change their minds. The problem is that there is no consistency. Some agencies delete and archive. Others delete and don’t look back. Many claim they’ve never ever deleted a tweet and that they never will.

How did this come to be? In May 2013, the National Archives and Record Administration, which is responsible for safeguarding federal records deemed to be of historical importance, released a toothless white paper on the best practices for the capture of social media records. According to the paper, “it is the responsibility of the agency to determine what kinds of content and metadata should be captured as records, weighing if these are adequate for preservation purposes.” Translation: Each federal agency decides how to treat its Twitter feeds, and a lot of agencies are making decisions on the fly about what to do, including negotiating what to delete.

Take this email exchange between two U.S. Patent and Trademark Office employees as evidence:

You might think that there should be a law that would prevent all agencies from deleting tweets left and right—but that law does not yet exist in the United States. Although the Federal Records Act governs agencies’ records-management responsibilities, it has left us with a problem:Aas a matter of policy, it isn’t a problem for federal agencies to delete their tweets unless their internal records-management staff has pre-established that tweets are “permanent records” and registered them as such with the National Archives and Records Administration. If it thinks that tweets are “non-records,” there’s no obligation to archive them. So, with regard to tweets, an agency has to elect to be transparent in the first place before we can expect it to be transparent. It all comes down to what the agency decides to put on its “records disposition schedules”—where federal agencies explain what records they plan to retain or destroy. (It’s worth noting here that the Federal Records Act is not the same as the Presidential Records Act, though I’d argue both are pretty toothless. This means that a whole set of different rules dictate the fate of tweets by the president. So tweets by @POTUS are not considered in the same legal light as those by @CIA or @TheJusticeDept.)

Deletions are not always driven by some master PR plan. Sometimes, they’re just proof that links break, things go awry online, as this deleted U.S. Army tweet illustrates. Who wants an error message at the top of their Twitter feed, right?

Agencies are supposed to consider public input when deciding their policies, but to be involved, you have to navigate a complicated bureaucracy. First, record retention schedules go through NARA’s internal review, where subject matter experts evaluate what agencies are saying they’ll preserve. Then, the public has 30 days to request a copy and provide comments. But to contribute to these forums meaningfully, you need to speak the language of “records” and “non-records” and “archives.” Few people are proficient in the terminology of law librarians, archivists, and records staff officers. That includes me: I’ve spent more than a year parsing the difference between a “record” and a “nonrecord.” It’s not fun.

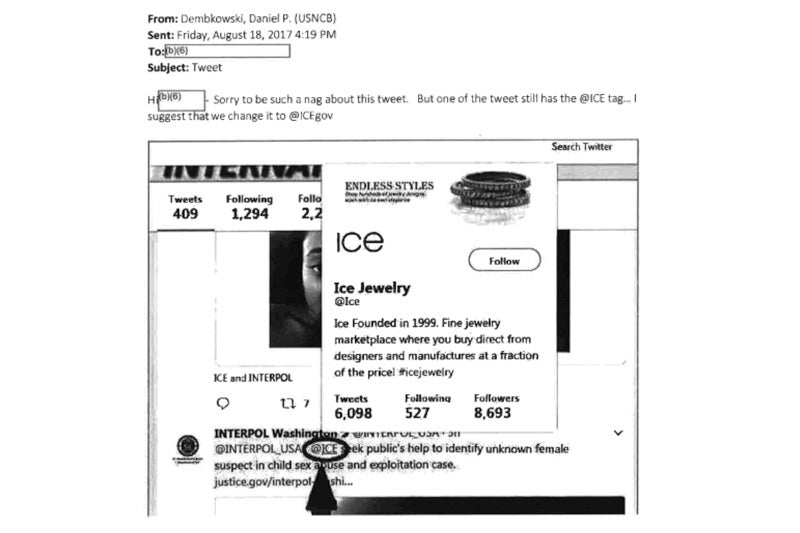

But, when we’re talking about deleted tweets, some of them are downright hilarious; this one from the Interpol’s account confused @ICEgov with @Ice. What a rookie mistake:

>Interpol tweet

Douglas Cox, an associate professor and the international law librarian at the CUNY School of Law, has written extensively on the Federal Records Act. He put it to me this way: “The [nonrecord] category ought to be confined to insignificant, nonsubstantive material, but exactly where the line is drawn is subject to interpretation and sometimes mischief or worse.” Back in 2007, the CIA used federal records laws to say that destroying interrogation tapes depicting the torture of alleged terrorist Abu Zubaydah was “in line with the law.” This past presidential election, the question of what constitutes a federal record surfaced again amid Hillary Clinton’s email controversy.

So how do federal agencies decide what is record-worthy in practice? Because my own academic work is on U.S. military policy, one of the first federal Twitter feeds that caught my attention was @thejointstaff, the official account for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. I reached out to Mark Patrick, chief of the information management division and acting joint staff records officer at the Pentagon, who patiently put up with a number of my questions about how the @thejointstaff is managed. Patrick said that they “focus primarily on the business value of information when making determinations, but also on historical value.” When trying to sort through records and make recommendations to the National Archives, he clarified, both legal counsel and the joint staff historian’s office is involved. Responses from other agencies I received were similar.

Updating federal retention schedules can take a painfully long time. For instance, while the Joint Chiefs records schedule doesn’t currently include @thejointstaff, Patrick expects that it will “long before 2021.” Obviously the federal government lives in its own time zone.

I went to vent my frustrations to Mary Rawling-Milton, who worked as an archives technician back in the 1970s and went on to write a dissertation in 2001 aptly titled “Electronic Records & The Law: Causing the Federal Records Program to Implode?” She pointed out that it is, in fact, difficult to figure out exactly what the heck agencies need to preserve when it comes to Twitter—and it goes well beyond just archiving every tweet: “Unlike our personal tweets, I would expect that any tweet on the official agency Twitter account to go through a vetting process prior to posting. Someone would approve the posting of the tweet,” she said. “If this is the case … the agency should preserve … the approval documentation.” And the approval documentation “should include a copy of what was to be tweeted, why it needs to be tweeted, the approval for the posting and, if they are good at recordkeeping, a copy of the actual tweet.”

The idea of asking agencies to include all of the people involved in the drafting of a single tweet cracked me up. There are simpler ways to proceed: Federal agencies could very simply take screenshots of all their tweets—ensuring that those records would exist if Twitter crashed tomorrow. I doubt anyone adhered to the highest level of recordkeeping, but I didn’t have any data to support my assumptions. So, I filed a number of FOIA requests with various federal agencies, starting with the Office of Government Ethics (@OfficeGovEthics).

You might remember that soon after the 2016 election, the OGE tweeted at Donald Trump about divesting his businesses. I asked it in December 2016 for “copies of all tweets deleted from 2014 to the present,” expecting nothing, but I was promptly rewarded with 218 pages of emails, including tweets that showed that the office staffers did draft the tweets using their government email addresses. I was grateful that for once a federal agency seemed to be fully transparent with me—dishing out not only the deleted tweets but also email correspondence related to them. (That seems about right for the Office of Government Ethics, doesn’t it?)

Feeling like I was on a roll, I went ahead and FOIA-ed deleted tweets from the Department of Justice (@TheJusticeDept) as well as “all internal policies, protocols, and written statements regarding the Department of Justice’s records keeping guidelines for their Twitter feed.” But the Department of Justice’s Office of Information Policy took a different route: It deemed my request “complex.” Almost a year later, I’m still waiting to hear back.

Not every FOIA office is as avoidant and elusive as the Department of Justice’s. Namieka Mead, a FOIA officer at the U.S. European Command, told me that their public affairs office follows “Best Practice” recommendations from the “Twitter Government and Elections Handbook.” That sounds great, but let me give you the tl;dr: In 137 pages, the word archive appears zero times. It’s kind of scary to me that federal agencies are merrily adopting Twitter’s norms and standards here. Twitter isn’t working for the good of American citizens, especially those who care about preserving U.S. federal records; it’s working for its users and its shareholders, who are focused on ensuring that the company turns a quarterly profit.

Some beautiful federal agencies are proud of their record as non-deleters. “Since the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) initiated its Twitter account in November 2012, we have not deleted any tweets,” wrote Kelly Fanizzo, the council’s associate general counsel.

Others bafflingly suggested that I should appeal to Twitter. “Please be advised, [Customs and Borders Protection] does not have the ability to pull deleted tweets from Twitter. You will need to reach out to Twitter directly for access to deleted tweets,” said Charlyse Hoskins, the government information specialist at the U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

I liked this extremely detailed paragraph from Damon Roberts, general counsel at the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Headquarters:

The standard operating procedure is to not delete tweets unless it is for clerical error. If a clerical error is discovered, the correction is made and the erroneous tweet is deleted. The content otherwise remains the same. … The current Social Media Program Manager has held his position since January 2013 and has advised the only instance a deviation from the standard procedure was earlier this month when figures presented in a tweet were incorrect. In that instance a screenshot was taken of the original message which was then deleted and reposted with the updated information which can be seen [here].

It’s nice that someone so competent has been at the helm of @USACEHQ since January 2013, but what happens when he leaves? Is this a firm policy, or is it just the practice of a very good employee?

The good news is that some federal agencies that have already stepped up to the plate and include Twitter in their federal records schedule. According to the 2016 Federal Agency Records Report, last updated on Oct. 2, 2017, “30% of agencies have approved records schedules covering electronic messages including text messages, chat/instant messages, voice messages, and messages created in social media tools or applications that meet the definition of a Federal record.” The Department of Justice, the Department of Homeland Security, the Federal Highway Administration, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration are among them. Still, for 2017, that’s an appallingly low statistic—even the Federal Agency Records Report calls it “only 30%.”

Many federal agencies aren’t particularly tech-savvy. Need proof? Here’s a screenshot of a deleted tweet that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office sent me recently.

When tweets get deleted, there’s little recourse. It’s not like you can call up Twitter and get the deleted tweet back. Trust me, I’ve tried. So, what can you do to get tweets included in the federal records schedule, if you want to discourage federal agencies from intentionally removing substantive material from the public’s eyes? Call up your favorite federal agency’s records officers? Dorky as it sounds, that’s exactly what I’ve started to do.

A few weeks ago, Adam Kriesberg, lecturer at the University of Maryland College of Information Studies, gave a talk at the National Forum of Ethics and Archiving the Web and warned about the risks that come when the American government relies on social media companies to get their messages out. (Full disclosure: We were on a panel together.) We need “[a]dditional approaches … to ensure that public sector information created on private platforms can remain accessible beyond the lifespan of any one platform,” he said. “Today’s Twitter could be tomorrow’s MySpace, but federal records require thinking on a much longer timescale.”

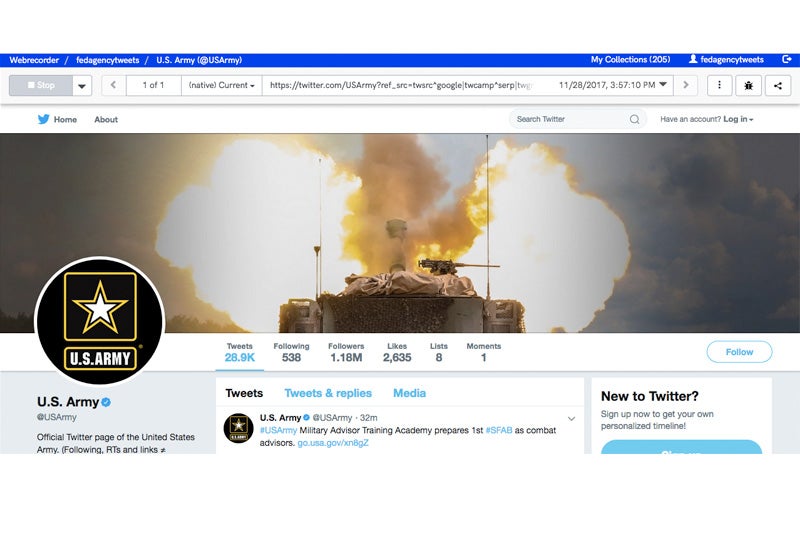

I’m not really worried about Twitter going off the grid tomorrow, but I’m uncomfortable with the fact that it has such great control over so much government-created expression. When I ask most federal agencies for their deleted tweets, at best they send me screenshots, and sometimes, those files look more like glitch art than anything else. So, partially out of frustration, partially out of fear, I’ve adopted another strategy: I’m using Rhizome’s Webrecorder to make my own high-fidelity web archives of each federal agency’s Twitter feed. (I received a small grant from Rhizome back in 2017 to support some of this work.) But even that system is incomplete. If I made a web archive of @USArmy on Nov. 27, 2017, it would not automatically add tweets posted afterward, and it wouldn’t capture tweets deleted on the account before Nov. 27. Still, to me, this approach seems a thousand times better than just accepting what I get back from federal agencies themselves or relying on the Wayback Machine’s crawler to grab all federal agency tweets before they’re deleted.

With Webrecorder, even if a federal agency takes its Twitter feed offline, I can still access and scroll through my archive.

I’ve spent thousands of hours now calling up federal agencies, filing FOIA requests, asking for records of deleted tweets, and making web archives of government Twitter feeds. I’m now beginning to look beyond the United States, looking into deletion binges and social media practices on government-run Twitter feeds around the world. I may be part of Generation Snapchat, but what I’ve learned is that I’m also unabashedly opposed to my government deleting or intentionally disappearing its own social media records. I’d love to see a version of Politwoops for federal agencies, but that’s a feat that I cannot undertake alone.

Over the years, I’ve come to feel this weird emotional connection to these Twitter feeds: I want them to live on in their entirety so that future generations can go back and see what a wacky world we inhabited. Is that really asking so much?

Read the strange tale of the Joint Task Force of Guantánamo’s missing tweets.