Explorer 1: The First U.S. Satellite

World Space Week 2020 will celebrate the impact of satellites on humanity from Oct. 4 to Oct. 10. Find out how to celebrate here and check out the history of Explorer 1, the first U.S. satellite ever to fly, below!

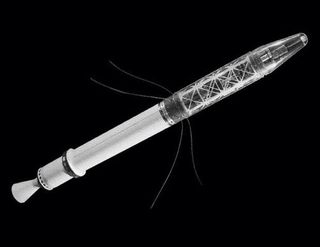

Explorer 1 was the United States' first satellite in space. The 1958 launch of the satellite — twice the size of a basketball — was an important moment for the country, as the Space Race with the Soviet Union was just beginning.

The satellite marked a moment when the United States got its confidence back after a series of unsuccessful launches and the Soviet Union's successful launch of Sputnik. The satellite also helped buttress the nation's technological confidence in the eyes of the world. It signaled that the country was ready to explore the universe.

Spurred by the Soviets

Explorer 1's ride to space came through a complicated set of circumstances. The United States had at least three main rocket options for sending the satellite into space. The ones that are most remembered today are Vanguard — under development by the Navy — and Juno. The latter rocket was based on an Army rocket designed by German scientist Wernher Von Braun, who worked on the V-2 missile program that sent bombs to England during World War II.

The satellite was supposed to launch as the United States' contribution to science during International Geophysical Year (which ran from 1957-1958). Then history intervened. The Soviet Union rocketed Sputnik into space on Oct. 4, 1957. This was the first artificial satellite any nation sent out of the Earth. The launch — revealed only after it was a success — stunned most of the Western world. It was a coup for Soviet rocket technology, and led some to muse that bombs could be launched just as easily as a satellite.

This accelerated the United States' plans. Rocket and satellite engineers quickly got to work, trying to prove they were also capable of launching into space.

Behind the Vanguard

On Dec. 6 of that year, a long two months after Sputnik, live reports of the Vanguard rocket carrying Explorer 1 broadcast in televisions and radios across the United States.

Vanguard, according to NASA, was chosen because it had more overtones of a civilian program — a policy decision going all the way up to President Dwight Eisenhower, who did not want the appearance of using ballistic rockets intended for military purposes to usher in the new Space Age.

Unfortunately, the rocket exploded moments after the launch in front of TV cameras. Amid headlines such as "Kaputnik," senior space officials took stock and examined their alternatives. Behind closed doors, they decided to proceed with the Juno rocket.

Preparations at Cape Canaveral went on in secrecy for weeks, according to NASA, but as the launch date approached the media was informed. Explorer 1 successfully flew into space on Jan. 31, 1958. A female team of scientists at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory calculated the rocket's trajectory, and team member Barbara Paulson recalled in an interview that she was the one confirming that Explorer 1 made it safely into space.

One of history's most famous space photos occurred that night. Von Braun and two other people held a model Juno rocket over their heads during a press briefing concerning the successful launch. It was a good night for the Germans, as well as for the American space program.

Explorer 1's science

Explorer 1's launch was a large policy coup, to be sure, but what was also interesting was the science the little satellite beamed back. Its prime science experiment was a cosmic ray detector designed by James Van Allen, a physicist at the University of Iowa. Cosmic rays are energetic radiated particles from space — bits of atoms that can include protons, electrons or nuclei.

The little satellite detected fewer cosmic rays in its orbit (which ranged from 220 miles from Earth to 1,563 miles) than Van Allen expected.

The physicist proposed this might be because radiation in Earth's magnetic field may prevent the cosmic rays from coming in. Explorer 3, launched in March 1958, discovered these magnetic field belts. Today, they are known as the Van Allen Belts.

Simplicity and reliability

Of Explorer 1's 30 pounds, more than 18 pounds of that was made up of instruments. Besides the cosmic ray detectors, it also carried experiments such as temperature sensors (both internal and external) and a microphone to listen for micrometeorites hitting the satellite.

NASA painted the instrument portion of the satellite white and dark green, which was supposed to regulate temperatures on the section. Dark colors absorb more heat, and white absorb less. The agency notes that the satellite was simple by design, as they wanted to ensure it was as reliable as possible.

On that count, NASA succeeded. Explorer 1 sent data back to Earth for four months, ceasing communications on May 23, 1958. The satellite remained aloft for more than a decade before re-entering Earth's atmosphere on March 31, 1970.

Explorer 1 spawned a series of other satellites. While Explorers 2 and 5 failed due to rocket stage problems, Explorers 3 and 4 both launched successfully in 1958 and transmitted science from orbit.

Even though the satellites are no longer working, their legacy remains. They launched the United States into space and showed that it was possible to do science from orbit.

Recent Van Allen belt findings

Explorer 1 discovered the Van Allen belts, and subsequent missions in the Explorer series uncovered more details about their nature. Today, the belts are being probed in more detail by the Van Allen probes, which launched in 2012. This is the first time that two spacecraft simultaneously studied the belts.

Shortly after their launch, the probes were turned on to supplement data from the SAMPEX (Solar, Anomalous, and Magnetospheric Particle Explorer) mission before the latter mission was concluded. It is not typical for a mission to start science observations right away as the instruments are still being configured. In this case, however, NASA wanted to take advantage of the probes being in space at the same time as SAMPEX. A fortuitously timed solar storm led to an immediate finding: the Van Allen probes uncovered evidence of a third belt affected by the storm, as well as the two belts that were already known.

The probes' mission is still ongoing, but some of the key science findings include:

- Examining how the radiation belts protect Earth from high-energy particles;

- Finding that the belts' shape depends on what kind of electrons are being studied (which means that depending on the electron being looked at, the belts can be unified or separate);

- Ongoing studies on how the belts change during geomagnetic storms. In 2015, the probes revealed an interplanetary shock (when charged particles from the sun create a shock in some areas of the belt).

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., is a staff writer in the spaceflight channel since 2022 covering diversity, education and gaming as well. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years before joining full-time. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House and Office of the Vice-President of the United States, an exclusive conversation with aspiring space tourist (and NSYNC bassist) Lance Bass, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?", is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams. Elizabeth holds a Ph.D. and M.Sc. in Space Studies from the University of North Dakota, a Bachelor of Journalism from Canada's Carleton University and a Bachelor of History from Canada's Athabasca University. Elizabeth is also a post-secondary instructor in communications and science at several institutions since 2015; her experience includes developing and teaching an astronomy course at Canada's Algonquin College (with Indigenous content as well) to more than 1,000 students since 2020. Elizabeth first got interested in space after watching the movie Apollo 13 in 1996, and still wants to be an astronaut someday. Mastodon: https://qoto.org/@howellspace