Soar Over Jupiter's Monster Polar Storms with This Stunning NASA Video

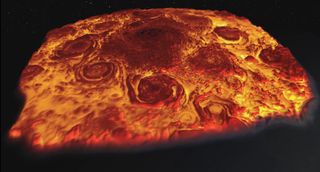

The massive cyclones that swirl near Jupiter's north pole glow like lava in a gorgeous new 3D flyover video captured by NASA's Juno spacecraft.

The Juno science team put together the 80-second video using infrared imagery gathered by the probe's Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM) instrument during a flyby in early 2017. Juno loops around Jupiter on a highly elliptical orbit, making such close polar passes once every 53.5 days.

"Before Juno, we could only guess what Jupiter's poles would look like," Juno co-investigator Alberto Adriani, from the Institute for Space Astrophysics and Planetology in Rome, said in a statement. "Now, with Juno flying over the poles at a close distance, it permits the collection of infrared imagery on Jupiter's polar weather patterns and its massive cyclones in unprecedented spatial resolution." [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

Those cyclones are indeed massive. The eight that surround the central polar vortex range in diameter from 2,500 miles to 2,900 miles (4,000 to 4,600 kilometers), NASA officials said.

The storms' resemblance to lava in the newly released video is of course superficial; we're seeing swirling air here, not melted rock. And that air is pretty frigid. The warmest parts depicted in the video — the deeper-down bits that glow yellow — top out at 9 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 13 degrees Celsius), NASA officials said. The darker regions are even chillier; the coldest spot is about minus 117 degrees F (minus 83 degrees C), they added.

The Juno team presented the new video Wednesday (April 11) at the European Geosciences Union General Assembly in Vienna, Austria. Mission scientists also unveiled another data product at the conference — an animation providing the first detailed look at the "dynamo" that powers Jupiter's intense magnetic field.

"We're finding that Jupiter's magnetic field is unlike anything previously imagined," Juno deputy principal investigator Jack Connerney, of the Space Research Corporation, Annapolis, Maryland, said in the same statement. "Juno's investigations of the magnetic environment at Jupiter represent the beginning of a new era in the studies of planetary dynamos."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The $1.1 billion Juno mission launched in August 2011 and arrived in orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. The solar-powered probe is studying the gas giant's structure, composition and magnetic and gravitational fields. Its observations should help scientists better understand how the planet formed and evolved, mission team members have said.

Juno will perform its 12th science flyby of the gas giant's poles on May 24. If all goes according to plan, many other close passes will follow.

"Juno is only about one-third [of] the way through its planned mapping mission, and already we are beginning to discover hints on how Jupiter's dynamo works," Connerney said. "The team is really anxious to see the data from our remaining orbits."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.