'We're just fed up': Teachers running for office in record numbers, motivated by low pay and education cuts

Lindsay Schnell

Lindsay SchnellFor decades, said Craig Hoxie, there’s been a joke in education that goes something like this:

Those who can, teach. And those who can’t, legislate.

Hoxie, who teaches physics and sports science at Booker T. Washington High School in Tulsa, Oklahoma, laughed when he repeated the line. But it’s not actually that funny, he said, because of the sobering truth behind it.

In the spring, when Hoxie and other teachers across the state walked out of Oklahoma classrooms demanding better pay, he thought of that joke. He thought of it again on the 110-mile march from Tulsa to Oklahoma City, as teachers rallied at the capitol for more money for education. That’s when he realized: If he wanted things to be different, he had to get involved.

“I’m always telling my students that to change things, they’ve gotta join the revolution,” said Hoxie, now in his 19th year of teaching. “And then I was like, ‘Well, I guess I’ve gotta lead it.’ ”

Prep for the polls: See who is running for president and compare where they stand on key issues in our Voter Guide

That’s how Hoxie, a 49-year-old Democrat with no previous political experience, found himself running for Oklahoma state representative. After beating another educator in the June primary, Hoxie has juggled lesson planning and knocking doors, balanced grading papers with making lawn signs, all in an effort to unseat Republican incumbent Terry O’Donnell.

And he’s far from the only educator getting involved.

Teachers have been in the news for months, as a profession in crisis gains public support after a wave of cuts to education. Lately, educators have been fighting back.

First, they protested. Earlier this year teachers staged statewide strikes in West Virginia, Arizona and Oklahoma, and they rallied in Kentucky, North Carolina and Colorado, closing some of the biggest schools. In September, teachers in about a dozen Washington state districts walked off the job as classes resumed, though many soon went back to work.

Now, teachers are running for political office – in staggering numbers.

Teachers on the ballot: 1 in 4 statehouse races

Educators in high-profile races include Jahana Hayes, the 2016 national teacher of the year, a Democrat who is likely headed to Congress to represent Connecticut’s 5th District. Former chemistry teacher Chrissy Houlahan, who got her start with Teach for America, is trying to turn Pennsylvania’s 6th District blue. In Wisconsin, lifelong educator Tony Evers is taking on Republican incumbent Scott Walker in the governor’s race, after Walker pushed a law that gutted the state’s teachers unions. (Walker insists he reformed education in his state, allowing schools to pay good teachers on merit.)

“This is reaction not to just teachers not having a voice, but the fact that we’re seeing the national discourse move away from education,” said Houlahan, an Air Force veteran who called teaching “the hardest thing I’ve ever done, hands down.”

“Truth, facts, science – those matter,” she added. “If we don’t educate, we’re going to continue to be a divided nation.”

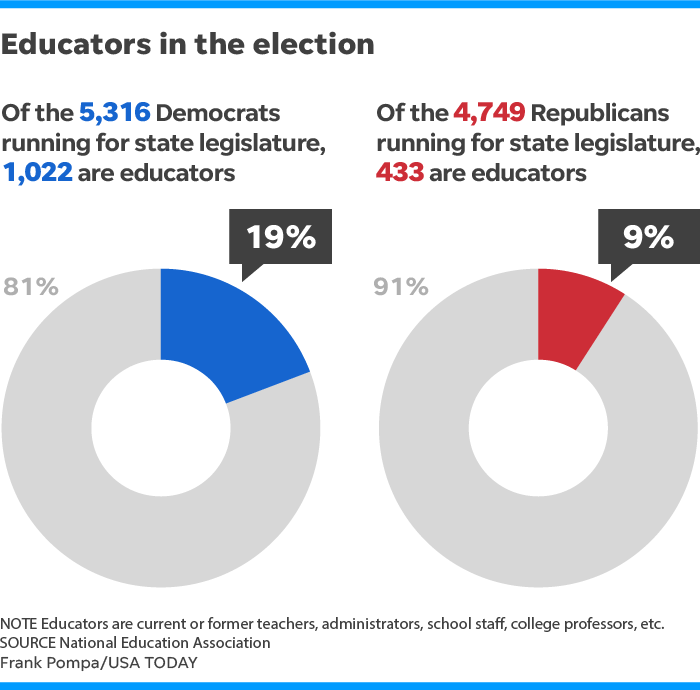

Decisions about money for education are made at the state level, which means teachers’ infusing state legislative ranks could have a profound effect on classrooms. According to the National Education Association, 1,455 educators are running in 6,066 state legislative races on Tuesday. That means someone with an education background – from classroom teachers to support staff to college professors – is running in nearly 1 in 4 statehouse races.

Teachers running for office is nothing new, but this scale is unprecedented, said Campbell Scribner, an education historian at the University of Maryland. For instance, more than 300 members of the American Federation of Teachers union are running for office — triple the number that ran in 2014 or 2016.

“Americans have always looked to schools to fix social problems,” Scribner said. “So teachers are in a unique position to win because people care about schools.”

Teachers across the country say they’re running for many other reasons, too.

“We see every day the impact of the opioid crisis,” said Tim Barnsback, a middle school engineering teacher and Democrat running for state representative for the second time in Morganton, North Carolina. Most of the children in foster care in his district are there because of their parents’ heroin or opioid use. “Teachers are on the battlegrounds fighting,” he said. “And we’re just fed up.”

When Hayes first got into the congressional race in Connecticut – ultimately advancing after a tough, close primary – many told her she couldn’t win because she was a single-issue candidate.

“I definitely begged to differ,” Hayes said. “When you have kids in your classroom who can’t learn because they’re worrying about adult problems, because someone lost their job and now they have to move, or they have an allergy but can’t get an EpiPen because their parents can’t afford it, those scenarios are playing out in teachers’ minds, while other people just see numbers on a budget.”

“Teachers have a front row seat to the future, and no one is asking us what we see and what we need.”

Oct. 17: We followed 15 of America's teachers. No matter where they work, they feel disrespect

DeVos' appointment 'woke up the storm'

Teaching, a profession typically dominated by women, has a history in politics: Lyndon B. Johnson, the 36th president of the United States, was a high school teacher before becoming a congressional aide and ultimately running for office.

But while men have a tendency to use education as a stepping stone, said Scribner, the education historian, women often get to elected office and become leading national voices on education. This is particularly true in many western states, he added, where women could run for school board before they could vote.

A former preschool teacher, U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Washington, got involved in politics after arguing that a preschool program shouldn’t be eliminated from the state budget. When a local lawmaker told her she couldn’t do anything about it because she was just a “mom in tennis shoes,” Murray responded by running for, and winning, positions in the school board, Washington state Senate and, ultimately, the United States Senate. Murray believes educators don’t just make great candidates, but also ideal legislators, because of their extensive background in collaborative learning.

She’s also not surprised to see so many teachers on the ballot.

The appointment of Education Secretary Betsy DeVos “woke up the storm,” Murray said.

DeVos, a school-choice advocate who favors some privatization efforts, was protested across the country, and her confirmation required a tie-breaking vote from Vice President Mike Pence.

“Teachers have been promised everything for so long, and they’ve seen the devastating effect of cuts in their classroom. They see the lack of respect public education is getting,” Murray said. “This has been building for a while.”

While most of the thousands of educators running next week are Democrats, roughly 30 percent of educators running in state legislative races are Republicans. That includes Toni Hasenback, a 7th grade English teacher in Elgin, Oklahoma. Hasenback actually ran for office in 2016, too, losing her primary by 93 votes.

Education, Hasenback said, is “the one industry that touches everybody.” And it is not a partisan issue.

Oklahoma is in a unique position with almost 60 educators running for state office in the general election. During this year’s walkout, teachers across the state realized political change was the only way to avoid future demonstrations, said Katherine Bishop, vice president of the Oklahoma Teachers Association.

“There’s been an awakening,” Bishop said. “Educators have always known they need to raise their hand and their voice to make a difference. But now we see we have to do that outside of the school buildings. We have to take it to the capitol.”

Melissa Provenzano, a 14-year educator who is running as a Democrat for House District 79 in Tulsa, has spent the last decade balancing budgets as a high school administrator. Every year since 2009, she’s had to make devastating cuts. “We are down to the bone,” she said. Like many educators running for office, her campaign is staffed largely by volunteer teachers, as well as some former students.

Should any of the 60 Oklahoma candidates win their election, state law will require them to resign from their teaching jobs to serve in government. This could put the Sooner state in a bind, said Hoxie. Oklahoma, where recruiting teachers is sometimes a challenge, is not equipped to fill all those positions. Hoxie, for example, estimates he is the only instructor in a 500-mile radius qualified to teach International Baccalaureate sports exercise and health science.

Elsewhere, teachers are making plans with long-term subs.

If Christine Marsh, the 2016 Arizona teacher of the year and a candidate for state Senate, wins a seat in Phoenix, her supervisor from her student-teaching days plans to come out of retirement and take over her classes during the legislative session.

Marsh finds the number of teachers running for office inspiring. But if she’s being honest, it’s also a little disheartening.

“In an ideal world, politicians would be taking care of business, and our students would be valued,” she said. “We should be able to close our doors and teach. But that’s not happening, so we have to step up.”

No matter what happens Tuesday, having this many teachers on the ballot proves “regular people have a place in government,” said Hayes, the Connecticut candidate for Congress. Going forward, they could aim higher, as they’ve always told their students to do.

“We’ve proven we can fight, and I believe we’re going to win,” Hoxie said. “And someday, maybe even within 10 years, we’re going to put a teacher in the White House.”