Teen magazines have two objectives. They have to gain readers’ trust with a tone that is conspiratorial but never condescending—a vernacular that mimics the way their readers talk when no adults are around. But they’re also grooming readers for the adulthood they’ll occupy in the not-so-distant future.

In the 1950s, Seventeen magazine ran ads for china patterns and silverware, anticipating the impending marriage and housewifery of its middle-class American female readers. Half a century later, a new magazine called Teen Boss—or, to quote its full title, Teen Bo$$!: Dream Big and Learn Fast!—prepares teens for a future where their best shot at security is not matrimony but a side hustle.

Teen Boss is a product of Bauer Publishing, the media group that publishes American supermarket checkout standards like In Touch, Life & Style, and Soaps In Depth. The print-only magazine, aimed at 8- to 15-year-old girls with an interest in entrepreneurship, rolls off the presses four times a year. The first issue hit US newsstands in September.

Tasked in 2016 with creating new titles for younger readers, Bauer teen group director Brittany Galla was drawn early on to the idea of a business-focused magazine. Surveys have found that this post-Millennial cohort, dubbed Generation Z, reports more interest in starting their own businesses than did previous generations. “In the many focus groups I hosted that year where I would just talk to girls about what their hobbies were and what not, I heard them talking about what they wanted to invent, the slime they were selling and their own business ideas,” Galla told Quartz. (Note: Kids these days are obsessed with slime.) “It’s really a guidebook for tweens to follow their dreams and go for it.”

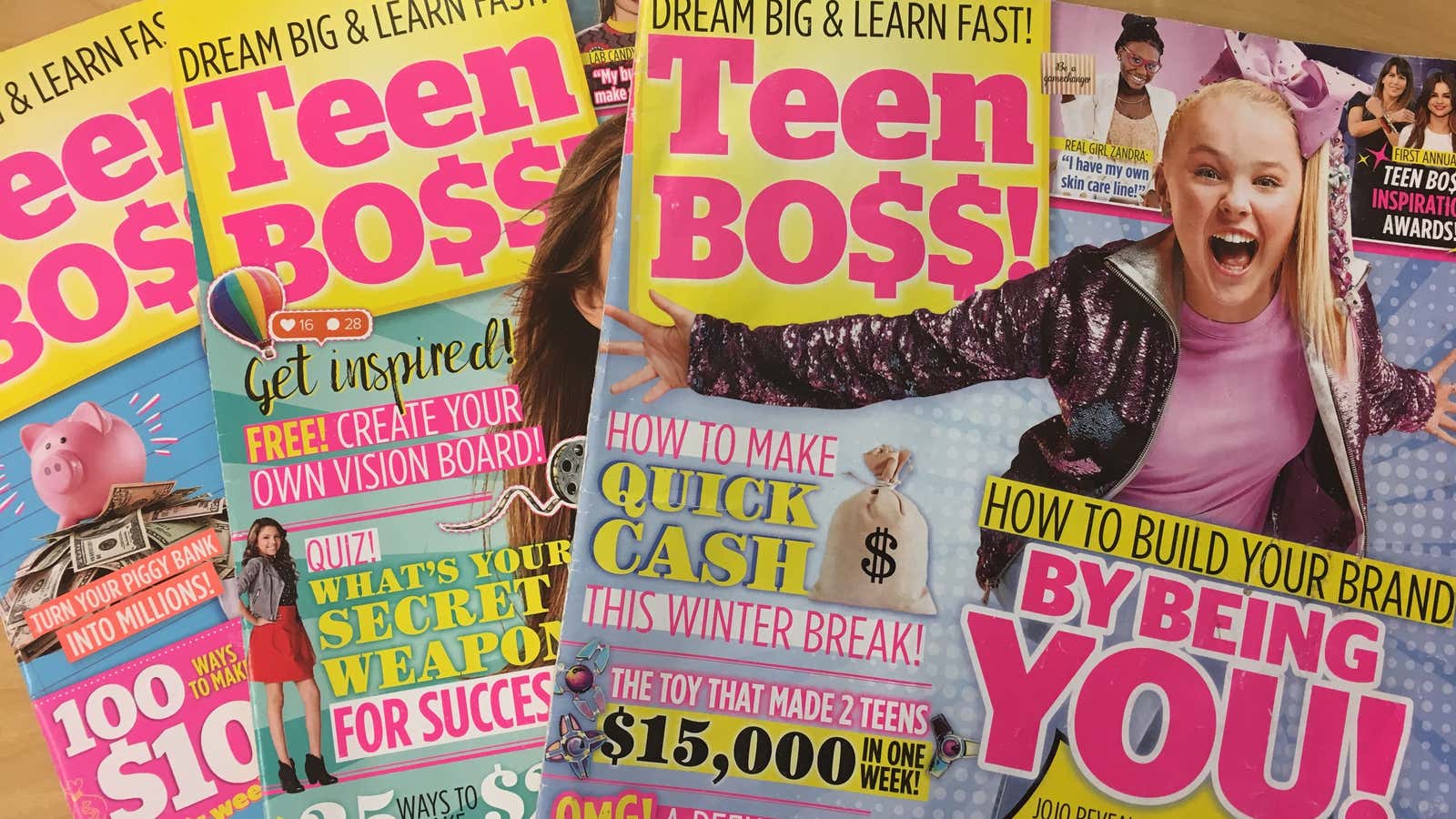

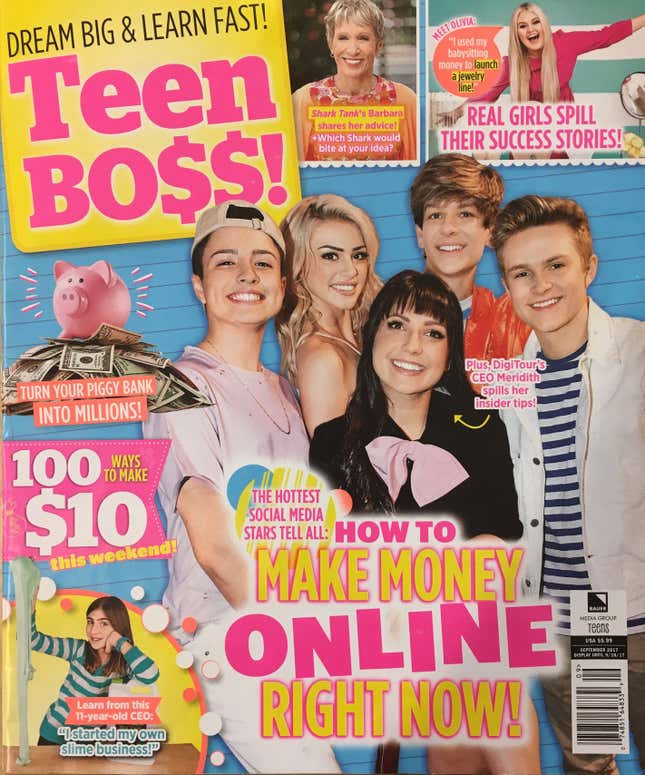

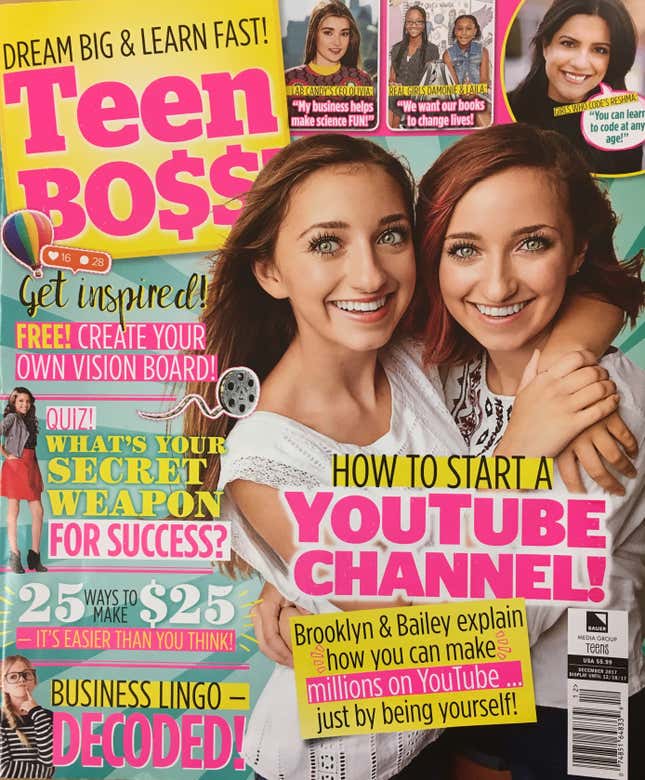

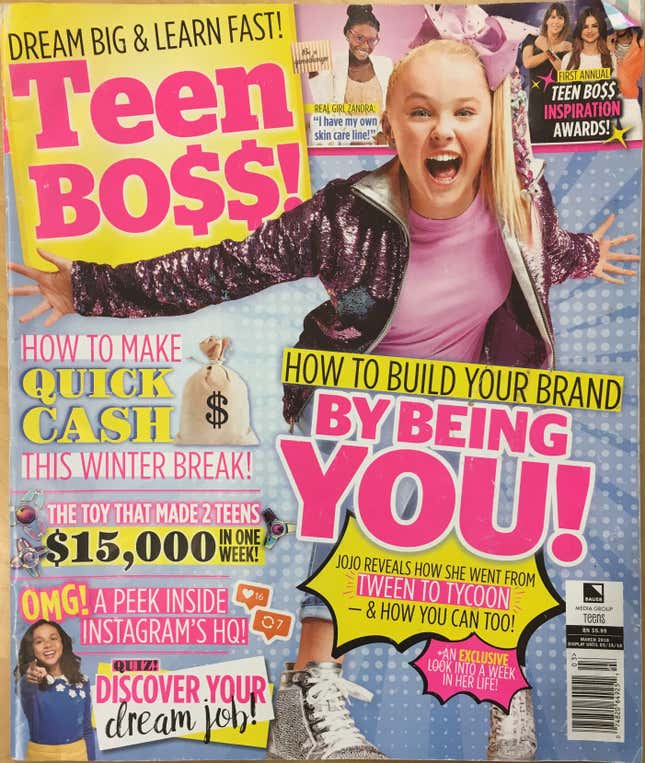

The covers of this guidebook are eye-searingly bright, with neon pink and yellow headlines like “How To Make Quick Cash This Winter Break!” and “Turn Your Piggy Bank Into Millions!” overlaid on photographs of adolescent YouTube stars. If you are over the age of 28 and do not regularly converse with preteen girls, you have never heard of any of the celebrities in Teen Boss, except maybe Barbara Corcoran of the TV show Shark Tank, who writes a monthly advice column. That’s ok. The whole point of a teen magazine is that if you are not a teen, it is not for you.

The inside of the magazine features girls’ magazine staples with a capitalist twist. There are fashion tips (“4 Ways to Rock a Blazer,” “10 Fashion & Beauty Rules to Follow At Work”) and quizzes like “Why Would You Slay As CEO?” and “Which Celeb-Preneur Are You Most Like?” The “-preneur” suffix is egregiously abused in the pages of Teen Boss.

There are also practical how-tos on drafting query letters and preliminary budgets that are as straightforward and helpful as any of the materials in the US Small Business Administration’s Learning Center, just with more pink.

A little help, a lot of hustle

The bulk of the ad-free pages are given over to short interviews with actual teen bosses, and my God, there are so many ways for teens to be bosses. There are teen bowtie designers and dog-food treat makers. There are teens who invented lollipops that supposedly clean your teeth and teens who invented anti-bullying apps.

Parental support is mentioned frequently in the interviews, financial and otherwise. “[My dad] asked me if I wanted to take the cup into production. I was 9 years old at the time so I didn’t really know what production meant, but I said ‘Sure, why not?’ and we went to China and found a little factory that helped us make them,” one 14-year-old inventor explains in a Q&A, to which the interviewer responds, “That was nice of your dad!”

But a lot of the teens profiled have more hustle than family connections or backing alone can provide. The September issue features a two-page spread on an 18-year-old woman named Maya Penn who has a sustainable fashion company, a nonprofit, a book, a TED talk, and membership in something called Oprah’s SuperSoul 100, which is described on its website as “a collection of 100 awakened leaders who are using their voices and talent to elevate humanity.” It’s the kind of CV that might make a 37-year-old woman mutter “Jesus Christ” while sitting alone in her home office.

How to be a boss

Coverage of Teen Boss has elicited a lot of handwringing about kids not being allowed to be kids and the toxicity of turning oneself into a brand and the cold hand of capitalism reaching out for innocent youthful necks. This anxiety feels misplaced. Every generation has a cohort of people who show an unusually high interest in and aptitude for paper routes, lemonade stands, babysitting, or the other money-making opportunities available to preteens. A preteen Warren Buffett caddied and searched the grounds of his local golf club for used balls he could resell, gigs that would be perfectly at home in Teen Boss’s “100 Ways to Make $10 This Weekend” feature.

The magazine’s misstep, though, is in the definition of entrepreneur that it emphasizes to its readers. While young business owners profiled include some examples of what are sometimes called “social entrepreneurs,” the featured celebrities on the covers of the first three issues are all YouTube personalities, and the cover stories of all three issues have been about monetizing a social media presence.

It reflects marketplace realities, sure—Buffett did not have the option to become an Instagram influencer in the 1940s—but it also promotes a narrow definition of entrepreneurship that even many adults buy into: the idea that a business’s primary purpose should be to increase the wealth and social profile of the person who started it.

But here the publishers may be confusing teens’ motivations for launching new products with their own.

What are today’s teen entrepreneurs really like?

Only the rare teen magazine (RIP, Sassy; stay strong, Teen Vogue) really gets their audience right. They are publications created by adults, for profit by adults, based on ideas adults have about who teenagers are. Their audience reads these magazine more critically than they’re given credit for, consuming some ideas, discarding others, recognizing themselves in some features and rejecting others outright, identifying with a felt but unseen cohort that no doubt feels the same way.

So what are today’s teen entrepreneurs really like?

Laurie Stach is the founder of LaunchX, which organizes a summer program and after-school clubs for American high school students interested in entrepreneurship. Students from the program have invented toys that help kids take medicine, smart water meters, and technology that cuts down on 3D-printing blunders. Stach sees a constantly replenishing stream of teenagers engaged with the world around them, and focused on bigger problems than that of their own status.

“While there are some who are motivated by the financial portion of it, more are focused on this internal drive to solve problems,” Stach said. “That’s something that’s really exciting about this younger generation of entrepreneurs. I’m so inspired by their interest in wanting to do good.”

In other words, the teens are all right, which is terrific, because one day you’ll be working for them.