Rare Soyuz 2-1v Rocket Launch Lifts Clandestine EMKA “Experimental Small Satellite”

Russia conducted a secretive launch out of the country’s primary military spaceport on Thursday, involving what is officially only known as a Small Experimental Satellite going by the acronym EMKA and suspected to be a former remote-sensing satellite design turned into a black project by the Russian Ministry of Defence.

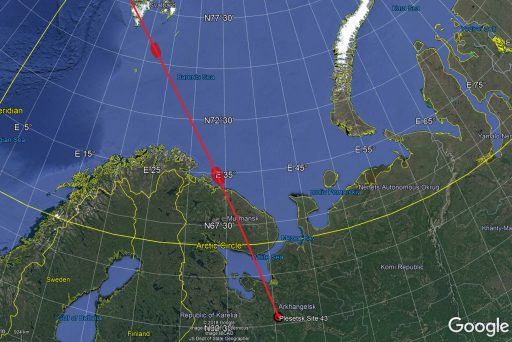

EMKA lifted off atop the fourth Soyuz 2-1v rocket at 17:38 UTC according to multiple Russian news outlets citing officials within Russia’s Space Forces that control military missions out of the Plesetsk Cosmodrome. Navigational warnings indicated the vehicle was heading north on a flight path consistent with a mission to Sun Synchronous Orbit or another type of polar orbit – the preferred orbital vantage point for imaging satellites of all types.

Confirmation of successful orbital insertion was provided around 16 minutes after the evening liftoff and tracking data collected by the U.S. revealed the satellite and the rocket’s upper stage in an extraordinarily low Sun Synchronous Orbit of 316 x 318 Kilometers, 96.64°.

Soyuz 2-1v – developed as a light-lifter to take over after the limited supply of Rockot boosters runs out – has conducted four launches to date, debuting in December 2013 as the third member of the Soyuz 2 family.

Since then, Soyuz 2-1v has exclusively launched missions of a military or intelligence-gathering nature, lifting the ill-fated Kanopus-ST mission in 2015 reportedly tasked with spying out the position of submarines, and launching the still-mysterious three-satellite mission around Kosmos-2519 in June 2017, reportedly dedicated to exploring satellite inspection and rendezvous technologies through several close passes between the three members of the mission.

Thursday’s launch also puzzled western observers as no clear candidate mission for EMKA was apparent when the launch showed up on the manifests in October 2017 with liftoff expected later that month. However, delays related to the mysterious payload first pushed the mission to November, December and eventually into 2018 with the launch date hovering around January and February before finally settling for late March.

The designation “EMKA” first showed up in late November through insurance filings made for the satellite’s air transport to the Plesetsk Cosmodrome which in turn tied the project to Roscosmos subsidiary VNIIEM that is responsible for a number of satellite projects including the Kanopus, Meteor and Resurs-O remote sensing and weather satellites. A number of VNIIEM presentations and reports around the 2016/17 time frame discussed a small remote sensing satellite “on the basis of an experimental small space apparatus” (экспериментального малого космического аппарата (ЭМКА).

The Russian Izvestia newspaper, by late December, had confirmed through its own sourcing that EMKA was procured from VNIIEM by the Russian Ministry of Defence. Izvestia also reported that the persistent delays of the launch were related to “technical problems with the payload.”

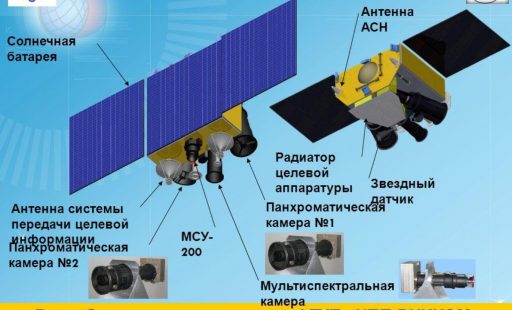

Around 2014, VNIIEM began presenting different small satellite projects under development by the company including an Extremely Low Earth Orbit small satellite concept called Zvezda to return 0.5-meter resolution imagery, a small-satellite design called MKA-V operating from a 450km SSO and finally a compact, high-resolution satellite capable of collecting panchromatic imagery, video products and stereo pairs.

According to insurance filings, a contract in connection to EMKA was signed between the Ministry of Defence and VNIIEM in October 2015 – meaning the mission went from the drawing board to the launch pad in just two and a half years, almost unheard of for Russian military-operated space programs in this day and age.

EMKA appears to be an interesting case of a spacecraft design originally envisioned for operation by Roscosmos or commercial entities being taken over by the government and turning into a “black project” – at least for the most part. VNIIEM openly discussed the EMKA project in 2015 and the satellite designation continued to show up in technical and financial documents in 2016/17 – some of these documents have since vanished from the company’s website.

EMKA apparently finds its roots in the MKA-V design, though its designation was changed to the more vague “experimental small satellite” which, as of 2016, was expected to launch in 2017 – matching up with the initial launch date for the Soyuz 2-1v mission.

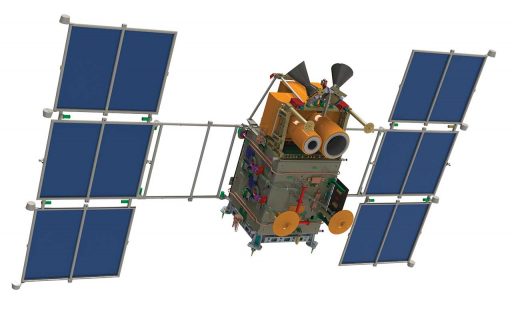

If indeed based on the Zvezda/MKA-V concept by VNIIEM, the satellite will weigh around 200-350 Kilograms and operate from some type of Sun Synchronous Orbit for a mission lifetime of at least five years, employing a Hydrazine propulsion system for orbit corrections and maintenance. The satellite’s payload would comprise one high-resolution and up to two wide-field imaging instruments capable of still imaging for high-resolution panchromatic imagery (0.6m resolution depending on altitude) and medium-resolution multispectral images, stereo product collection and video acquisition.

A trend toward smaller satellites in the space-based reconnaissance sector has been evident in a number of programs over recent years, i.e. China’s Yaogan-30 constellation that launched 12 satellites in just four months. They can be built and launched fairly inexpensively and in large numbers while still delivering reconnaissance products nearly matching the quality of those gathered by large satellite missions.

Whether EMKA is a pathfinder mission for a future Russian system of small reconnaissance satellites or if it fulfills a dual-purpose civilian-military mission remains to be seen.

The satellite launched on Thursday was named Kosmos 2525 under Russia’s naming convention for military-operated missions. Some information on the satellite’s identity may come through the official launch announcement expected later on Thursday and its operational orbit and potential maneuvers will be revealed through orbital data collected by U.S. Space Surveillance over the coming days and weeks.

Thursday’s launch was only the fourth in the career of the Soyuz 2-1v rocket – a highly modified single-stick version of the Soyuz workhorse intended to provide light-to-medium lift capacity by combining many flight-proven technologies from different launcher families. The vehicle is the first flying under the Soyuz designation and not using the iconic R7-based design with four boosters around a central core – an architecture that has been in operation since 1957.

>>Soyuz 2-1v Launch Vehicle Overview

Instead, Soyuz 2-1v relies on a modified Block A first stage hosting a single NK-33 main engine that finds its roots in the ill-fated N1 lunar rocket developed in the 60s and 70s plus an RD-0110R four-chamber steering engine adapted from the Block I third stage of Soyuz. The second stage is identical to that of the Soyuz 2-1B rocket – using the more efficient closed-cycle RD-0124 engine and the modern digital control system to make the vehicle more flexible.

Soyuz 2-1v stands 44 meters tall, is 2.95 meters in diameter and has a launch mass of 157 to 160 metric tons, capable of lifting up to 3,000 Kilograms to Low Earth Orbit and 1,400 Kilograms into a Sun Synchronous Orbit with the help of a Volga Upper Stage. EMKA alone – if indeed riding solo – would have been a particularly light load, even for the Soyuz 2-1v, but Russia does not have any smaller launch vehicles available at this time: all remaining Rockots are assigned to missions and others like Strela, Volna and Start-1 have not flown for years.

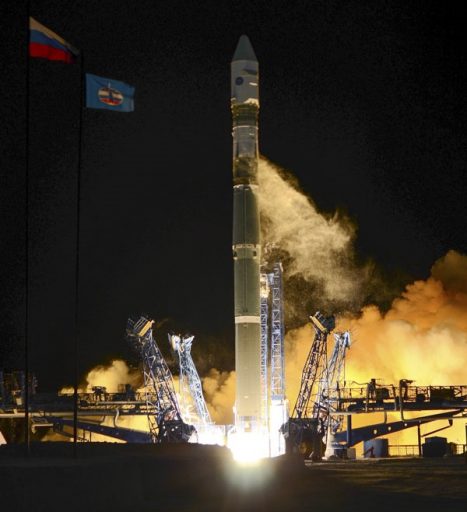

Gearing up for its post-sunset liftoff, Soyuz 2-1v received 145 metric tons of rocket-grade Kerosene and sub-cooled Liquid Oxygen – necessitated by the use of the NK-33 that relies on the lubricating properties of oxygen below its boiling temperature. Illuminated by flood lights, Soyuz was to be revealed atop its pad around 30 minutes to liftoff when the two halves of the Service Structure were to be retracted followed by the start of the critical final countdown sequence at T-10 minutes when chilldown of the NK-33’s turbomachinery was to begin.

Liftoff from Plesetsk Site 43/4 occurred at 17:38 UTC, 8:38 p.m. local time and Soyuz 2-1v was set for a brief vertical climb before turning to the north west, targeting a retrograde Sun Synchronous Orbit, per navigation warnings issued for this mission which pointed to an orbital inclination in the neighborhood of 97 degrees.

Powered uphill by its single NK-33 and four-chamber RD-0110R, Soyuz 2-1v pierced into the night with a thrust of 1,844 Kilonewtons. Providing 11.6% of total thrust at liftoff, RD-0110R also contributes to overall vehicle performance and is not a pure steering engine.

The first stage of the Soyuz 2-1v shares some commonality with the Soyuz 2 vehicles, but a number of components are changed: the diameter of the lower section of the stage is increased to 2.66 meters while the maximum diameter remains at 2.95 meters and overall length also remains at 27.8 meters.

Soyuz 2-1v also retains the hot staging sequence between the Block A first stage and the modified Block I second stage, occurring around three and a half minutes into the flight when the RD-0124-powered second stage fires up and the separation pyros initiate to enable the second stage to head on toward orbit.

Shortly after ignition of the Block I second stage, the protective payload fairing of the rocket was to be jettisoned, headed for an impact 1,550 Kilometers from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome. The 6.7-meter long Block I stage was tasked with a burn of around four minutes and 35 seconds, consuming 25 metric tons of LOX and Kerosene with its gimbaling 294.3-Kilonewton four-chamber engine.

The presence of a Volga upper stage on Thursday’s mission has not been explicitly ruled out and performance of the two-stage version of the 2-1v launcher would easily permit a satellite like EMKA to be directly injected into its operational orbit. If that was the case, orbital insertion would have occurred around eight minutes after liftoff; if a Volga upper stage was employed to ensure a precise orbital injection, separation of the payload would occur around an hour after launch following a two-burn injection.