How call centres help the Philippines rebrand as a hub for service excellence

As the global economy’s biggest ‘back office’, the Southeast Asian nation is increasingly seeking to depict its workers as educated, empathetic and fluent in English

What changes in a country – and what does not change – when it devotes itself to servicing the businesses of other countries? Not long ago, I found myself looking for answers to that question in the busy district of Makati, in the Philippines’ capital Manila, during a meeting with Melvin Legarda and Joseph Santiago, executives at the Business Process Outsourcing Association of the Philippines.

The organisation’s mission was to entice foreign businesses to outsource back-office work – such as accounts receivable and medical billing and, of course, customer service and technical support call centres – to the country.

Call centres are big business in the Philippines, and while I was a doctoral student at New York University, I spent time there researching the industry between 2008 and 2013. During that period, the former American colony became a top destination for outsourced jobs from industrialised countries, the United States chief among them. In 2011, the Philippines surpassed India to become the world’s capital of call centres.

I am a Filipino-American woman, and I received a warm greeting from Legarda and Santiago (both thirty-something men in suits), along with the familiar roster of questions about my place in the Philippine diaspora: was I born in the US? Are my parents both Filipino? Do I speak Tagalog? As our interview progressed, however, it was clear that Legarda and Santiago regarded it as just another opportunity to market the Philippines as a high-quality source of call-centre labour for companies looking to outsource jobs to a low-cost, offshore location.

In a small conference room filled with motivational posters and ample air conditioning, they enthusiastically explained that it was their organisation’s job to make sure people around the world know that Filipinos are fluent in English, highly educated and literate in media and technology.

I was not surprised by my interviewees’ approach to our meeting, but one part of the marketing spiel that caught my attention was their discussion of Filipino identity. Speaking in lofty, almost romantic tones, they argued that Filipinos possess an innate capacity for empathy, compassion and general “service-orientation”, and thus are ideal for call-centre work.

They went on to explain that Filipinos are also quite “flexible” (read, easy to train and able to multitask), a feature that helps in the world of contract labour, where a worker’s job description often changes according to client demands.

The dynamic and proud young Filipinos driving economy rated ‘Best to Invest’ in 2018

The roots of Filipino identity, they elaborated, were grounded in the country’s experience of colonialism, occupation and debt. After more than 300 years of colonisation by the Spanish, US colonisation in the first half of the 20th century, Japanese occupation in the second world war and the severe debt crisis of the late-20th century, Filipinos had become a benevolent and compassionate people, which made them perfect for serving a wide range of customers over the phone.

This was not the only time these beliefs about Filipino identity surfaced during my research. I heard them from the dozens of workers that I interviewed, and throughout the hiring and training I myself underwent in a call centre later. The grip these ideas had on people prompted me to think that Filipino identity was not simply affected by the spectacular growth of the call-centre industry, but actively constructed within it.

State support for overseas labour migration began in the 1970s, with the Philippine government actively encouraging its citizens to pursue work in the US and oil-rich countries of the Middle East. In recent years, the number of migrants leaving the country to work abroad as domestic helpers, seamen, nurses or service-industry workers has reached 1 million annually. Meanwhile, migrant remittances – the money sent back home to support loved ones – have grown to make up roughly 10 per cent of the country’s GDP, or US$33 billion. In the late 20th century, the Philippines’ top export became its people.

When labour becomes a country’s No 1 commodity, the identity of the people providing that labour becomes an object of marketing rhetoric – something to brand and sell – especially amid global competition with other national, racial or ethnic groups for the jobs in question. Such competition compels many Filipinos to search for immutable traits that tell potential employers: hire us, because you will not get this kind of labour from anyone else.

According to Philippine-based employment agencies that try to place workers in jobs abroad, Filipinos – especially women – are naturally caring and tender people, not to mention loyal, cooperative and compliant

Take commercial seafaring on container ships or other cargo ships – a common job for Filipino men. In that industry, workers, state officials and corporate actors alike evoke the long history of Filipino seafaring – as well as the Manila-Acapulco galleon trade in silver and Chinese goods that the Spanish ran between the Philippines and Mexico – as proof of Filipinos being fit for life and labour on the sea.

Similar dynamics apply to nursing and domestic work. According to Philippine-based employment agencies that try to place workers in jobs abroad, Filipinos – especially women – are naturally caring and tender people, not to mention loyal, cooperative and compliant.

The rise of offshore call-centre work follows this basic structure of labour migration but with a crucial difference: Filipino workers are not required to leave the country. Instead, they are employed by third-party foreign companies – business process outsourcing (BPO) companies that contract with corporate clients, such as Citibank or AT&T, which are looking to outsource customer care or back-office processes.

The call-centre industry takes that same identity branding further, with workers and industry leaders alike saying that call-centre work reveals three special characteristics of Filipino people in the 21st century.

First, since call-centre work involves engagement with information technology, it ostensibly shows that Filipinos are prepared for knowledge work and thus the future as a whole.

Second, since the work requires the use of mental and social capacities, call centres mark the evolution of the Philippines beyond bodily labour.

How the Philippines can play peacemaker in Asean while banking on goodwill with China

Third and finally, many of my research participants saw the country’s burgeoning call-centre industry as a clear sign of the country’s rehabilitated status. In the global economy, the Philippines, with its role as call-centre capital, could no longer be dismissed as the “sick man” of Asia. Indeed, it was a business partner to the US, rather than a supplicant to other countries.

In this light, the Philippine call-centre industry was not just an economic pivot for the country, but a cultural fulcrum that could redefine Filipino identity for ages to come.

What could be the danger in that? Should exploited and dispossessed people not have an opportunity to define themselves?

My answer to this question is yes, but my research in the Philippines revealed many nuances and problems when Filipino identity formation is so closely tied to call-centre work.

The new identity also makes other distinctions that are problematic. Industry leaders’ assertions that Filipinos are prepared for high-level knowledge work in call centres devalues jobs done at the lower end of the value chain in centres, such as customer care.

Consider the commencement speech given by Juan Miguel Luz, a former dean at the Asian Institute of Management, in Makati, to graduates of the University of St La Salle, in Bacolod, in 2013. Luz’s address recognised the city’s emergence on the call-centre scene but also characterised customer service as the “least-skilled” knowledge-based work, since it involved “simple questions or problem-solving [sic]”.

The introduction of the call-centre industry in the Philippines reinforces these beliefs, in part by implying that technology has made the Philippines a stronger country

Bristling at this description, call-centre workers criticised the speech on social media, explaining that customer service was worthy work requiring a great level of competence. The protest prompted Luz to issue a letter of apology in a national newspaper, in which he attempted to clarify the range of communication, technical and emotional skills the job requires.

Luz’s speech helps point out that what we consider a good job is often wrapped up in how we judge work done with our hands, hearts or brains. There are deeply held beliefs that work requiring one’s body or emotions is inherently less valuable than work that draws on the mind, including the use of technology.

The introduction of the call-centre industry in the Philippines reinforces these beliefs, in part by implying that technology has made the Philippines a stronger country. The industry itself is an outgrowth of massive changes made by the government in the mid-1990s to national communications and tech-related policies, that made it easier for foreign companies to invest in the country’s IT systems.

What happened to the billions China pledged the Philippines? Not what you think

Along with these changes came improvements in the Philippine economy overall – including high economic growth, partnerships with regional economic associations and achieving investment grade status – that supposedly make the Philippines capable of knowledge work and invulnerable to the predations of stronger countries.

Yet this is a dream in which the bullied join the ranks of the bullies (and that is exactly the dream that has become a nightmare under the current bullying Philippine president). The future of the call centre is not different enough from the past; there is no reassessment of the power dynamics that shape economies and lives. The Philippines has long been and continues to be a source of low-cost labour for the world. Call centres, while providing much-needed work, are unlikely to change these dynamics.

Identity construction can sometimes be seen, mistakenly, as an inherently positive process – especially for a postcolonial country such as the Philippines. Deeper change in Filipino identity will require changes in the very structure of global institutions and the distribution of power and resources. Perhaps then, the construction of Filipino identity will no longer be constrained by the marketplace, and more Filipinos can define themselves by their own dreams. Economic necessity cannot be ignored, but it should never determine who people are.

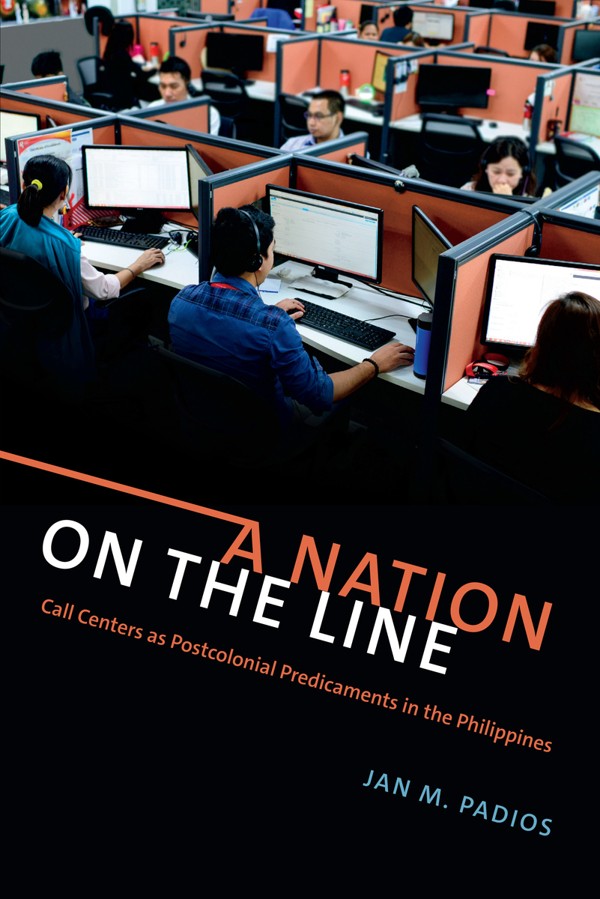

Jan M. Padios is an assistant professor of American studies and affiliate faculty in women’s studies and the Asian-American Studies Programme at the University of Maryland. Her first book is A Nation on the Line: Call Centers as Postcolonial Predicaments in the Philippines (2018). This article was produced by Zocalo Public Square (zocalopublicsquare.org).